As we left the Overground transport train and entered into the Hackney area of London, I became utterly confused. Spending the last decade in New York City, I was used to a regular grid and quickly gaining my orientation within the urban landscape. Not so easy in London. I followed my friends, who had visited Sutton House before. They knew where they were going. I followed like a little kid trying to keep up with his parents. I don’t know why, but I always find myself at the back of walking groups. Maybe it’s because I am getting old and my stride is slower but being in the back of the line gives me a front-row view for surveying the environment. I sometimes feel like I am an elementary school kid, sitting with my grandmother in her kitchen, helping her put together one of her many puzzles. We would first lay them all out, image side up, and then she would begin surveying the lot to imagine a world where these came together, fit together perfectly, and produce (in this case) a puzzle of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper. I remember when we finished this puzzle, she glued it down to a piece of cardboard and framed it. It remained above the breakfast table in the kitchen until she passed away. After the house was sold and emptied, I never saw it again.

My confusion over directions to Sutton House reminded me of the initial confusion I felt when my grandma set out to produce her Last Supper puzzle. I knew eventually it was supposed to make sense, but at that moment I didn’t see it. I have to be honest – I feel confused most of the time. I am beginning to turn into the “Mr. Magoo” of the museum world. My problem is that my personal perspective on heritage and visitor experience seems to be out of line with many professionals working in the field. Like the image on the cover of the “Mr. Magoo” book, I feel like I am trying to hang up a coat inside of a grandfather clock.

As we walked, I took notice of a “Sutton House” street sign. “We must be close,” I thought to myself as I trailed the others. As we approached the National Trust of the United Kingdom site, I recognized it, but it didn’t really hold any presence from the street. It felt like a single instrument in an orchestra – important in the collective, yet it didn’t stand out. The house rests on a busy spaghetti plate of roads, which lessens the threshold quality of the entrance. The house isn’t, in a stereotypically romantic sense, photogenic. In fact, the overlaying of contemporary and traditional elements causes, at first, a disconnect. Across the street from the heritage site is a new, mirrored, blue glass building; organized and geometrically tidy, as if to mock the Sutton House for its less than perfect alignments.

This confusion continues when I am told that the house, even though it is called “Sutton House,” was never the dwelling of Thomas Sutton. All historical documents suggest that he lived next door rather than in the house that now bears his name. In doing a bit of research, I distinguished how the original roads looked and compared it to today’s transportation system. In many ways, the two are very closely aligned with the exception that what used to be open farmland is now densely packed with residential buildings. Sutton House estate, originally called “Bryk Place” (c. 1534-5), was a free-standing walled estate resting comfortably among long open green spaces. The town center of Hackney was close by and within walking distance. I think I found my first set of puzzle pieces.

The house itself aligns perpendicularly to the street side and then shifts toward the southeast on the rear. Thus, begins the awkward, and wonderfully ill-aligned composition. All of this urban torque seamlessly continued as I entered the house. The two back wings of the house were separated by an exterior courtyard. There felt a peculiar relationship with the street, as the entrance space was catawampus and seemed crammed between the house and the street. Immediately upon entering, our hosts asked if we wanted to have tea or go straight into the Queer Tango class.

Of course, we said, “Queer Tango!”

We quickly left our bags in the gift shop and headed out to the large community room at the back of the house complex. You could hear the music from out in the exterior courtyard, becoming louder as we opened the door into the transitory dance hall. A huge smile took over my face as I became aware of what “Queer Tango” involved. The room was full of roaming, tango-ing same-sex and opposite-sex couples in a dancing embrace. We were immediately pulled into the class and invited to tango. While attempting (poorly) to tango, I was struck by the need for a collaborative effort between dominance and passivity; between control and release; between the intellectualization of the steps and the spontaneity of the action. The complexity of the dance pulled me out of my head and into the physicality of the effort.

The history of the tango has its beginnings in the brothels and common cafes of Buenos Aries at the turn of the 20th century. Originally a dance between two men, it has been theorized that the dance was a way for the sexualized men to pass the time while waiting for the next sex worker. The dance was more like unison mortal combat between men than the embracing opposite-sex dance of today. I found this transformation from one emotional extreme to the other compelling – how can forms remain the same, and the emotive directive evolve? The complexity of this transformation was well housed in Sutton House.

For the past two years, Sutton House has initiated a new community-based program called, The Queering of Sutton House. It involves interpretive and programmatic insertions into the established heritage narrative of the site that presents various LGBTQ happenings and exhibitions. They have received much praise and press for their unabashed pursuance of such empowered and forward-thinking efforts. This is one of the reasons that we wanted to hold a “One-Night Stand” at Sutton House because the staff seemed not only willing but seeking expansive community engagement beyond the traditional heritage site audience.

In some ways the irregular and surprising form of the house, and the jarring way in which it engages the street seem analogous to the manner in which the staff has approached their innovative programming. It’s as if the house somehow manages to accommodate nonnormative, behaviorally off-center in a way that feels wholly comfortable and expected. The queer’d and, at times, camp interpretation clearly targets a self-important aspect of heritage sites. The Sutton House happenings force a level of self-reflection upon the heritage community in ways that are unexpected. In transforming traditional heritage elements into elements of camp and humor, it manages to dig to the core of some of the problems with these sites –that narratives, as well as the very experiences, seem to have been created to maintain the established, heteronormative establishment view of habitation. This problem is something that I have often attempted to address in my writings and speaking events. Just ask yourself how do history sites address sexuality, fetish, behavioral and mental experiences? Do we all not deal with these issues every day? Were, in this case, the English Tudors exempt from these normal life experiences?

After our Queer Tango class, we headed up to the “squat room.” Did I mention that the Sutton House, while abandoned back in the mid-1980’s became a squat for a group of community-minded punk rock anarchists? The room that we are sleeping in for this “One-Night Stand” is a room that has existing graffiti from this era and has been curated into a period room from 1984. The squat room is on the upper-most attic level. The low roof trusses make it hard not to bash your head as you enter the room. Our bed for the night was a basic mattress resting directly on a couple of pallets. There was also a decaying sofa, beanbag, and a few makeshift side table-like things holding a mix of light fixtures, books, and artifacts. On the windows hung tie-dyed cloth and various pieces of different sized fabric. On the wall were murals painted by the squatters.

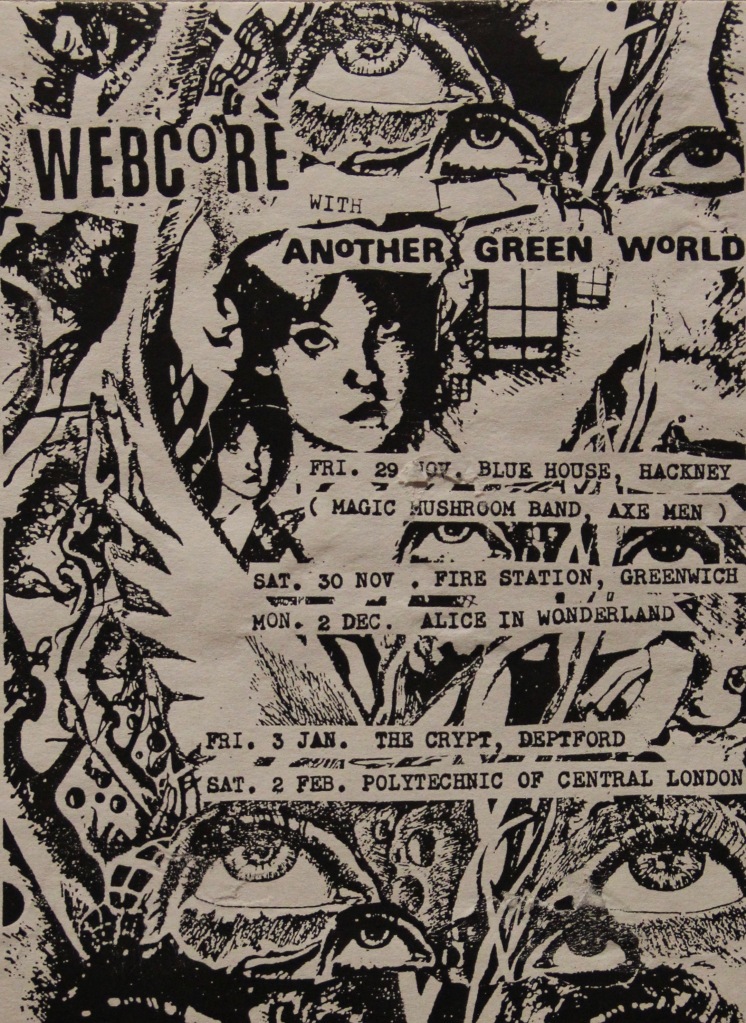

As we were unpacking, our hosts brought in a collection of advertisements for the “Blue House.” The Blue House was the name given to the Sutton House by the squatters. The goals of the squatters were to turn the abandoned house into a community center with a super8 cinema, a music venue, and café. The playbills that we were shown were posters advertising the various music shows that took place at the house. In addition to the poster collection, there were various editions of the Squatters Handbook. The Squatters Handbook has been published by the Advisory Service for Squatters in London since 1976. It is now in its fourteenth edition and provides over a hundred pages of detailed legal and practical information about squatting and homelessness in England and Wales

In many ways, the goals of the squatters continue with the National Trust’s interest in making Sutton House an engaging heritage site for a wide community. The inclusion of the squat room as an interpreted element in the narrative is an example of this intent.

Over an Italian dinner with the Sutton House staff, we discussed the relationship of the Queering of Sutton House to our own personal lives. I was interested in how current elements of our intimate lives could engage a heritage site. By dessert, I realized that, at least in our group, the fluidity of sexuality, gender pronouns, monogamy/open relationships, bisexuality and other relationship models made it impossible to designate an orderly or even standard model of behavior. I wondered to myself how such social fluidity would be expressed 100 years from now in a heritage site? How our views would affect the built environment? Surely these lifestyle choices were not unheard of during the Tudor period of the Sutton House (and squat room era).

Back at the house and after getting ready for bed, I wandered the sunset darkened rooms. At twilight, the odd angles overlapped built forms, and misaligned shapes became even more strongly felt. My internal attempt, just as when I was a kid with my grandmother creating that puzzle of the Last Supper, was to fit the pieces together; to make sense of the architectural chaos that is the house. Outside of myself, I realized that I was in the middle of an intellectual tango, mediating between the dominant normative idealized desire and the marginalized counter-normative of reality. Even stopping once and a while to peek out of the windows, I was reminded of my skewed relationship with the outside world – who was following whom in this dance of history?

The night was uneventful. Needless to say, the thin mattress on pallets wasn’t the softest bed I had slept on – but it also wasn’t the worst. Waking up slowly in bed, I took notice of the room and its contents. The haphazard feel of the furnishings, along with my own bags, shoes, and clothes blended seamlessly into one environment. There was a comfort in the relationship between my personal items and those of the curated period room.

As the sun rose in Hackney London, I took a final walk-about through the site. I walked into dark room after another, making odd turns and stepping up and down various stair elements finally exiting the first-floor hall out into the open-air courtyard. The sky was bright blue, and the house jumped out against the flawless expanse. From the courtyard, I unintendedly wandered out into what is called the “Breakers Yard.” Formerly a derelict car breakers yard, the garden site next to the Sutton House is now a unique blend of installations and hidden spaces connected by undulating brick paths. Award-winning landscape designer Daniel Lobb and arts-based educational charity, The House of Fairy Tales (led by Deborah Curtis and Gavin Turk) created the garden in partnership with Sutton House.

The centerpiece of the Breakers Yard is a 1970’s caravan camper which has been re-interpreted as a fancy manor estate house. It was in this garden that I really felt the puzzle pieces coming together for me. The integration of contemporary installations, the acceptance of a continuous narrative rather than the typical narrow “period of significance,” along with the backdrop of the house itself all combined to produce a unified, yet complex whole. Sitting in the caravan manor house and looking back toward Sutton House magnified the non-normative quality of the experience a visitor feels at the house. It’s almost as if there are many layers of translucent fabric, each with their own history shadows imprinted on them, all blowing in the breeze and forming a live, current, unique, moment of interpretation. There is nothing standard and stable about this moment.

As I sat in the Breakers Yard, typical of England’s weather, the sky went from bright blue to overcast with billowy clouds. I looked back at the house and snapped some pictures. I was in the moment, so I had no time to reflect. Rain began falling, and I went back inside of the house. It wasn’t until later when I downloaded the pictures to my computer that I noticed the emotional change that came over the house once the clouds came in. Again, Sutton House surprised me with its nimble ability to be many things at the same time. It, in itself, manifested a continuum of history that with ease embraced me at the same time it stood as a fragment of a past era. My time at Sutton House ranged from Tudor 1500’s, straight through the 1980’s squat, and right into the present day as I sat in the Breakers Yard installations. The house also had the strength and courage to take on messy, controversial, and complicated issues presented by the amazing Queering of Sutton House. This heritage site is no stranger to any of this. In fact, I left Sutton House feeling like I just had a life lesson from a very wise elder.

Don’t write off this place a “merely old” – you do so at your own loss. Put on your feather boa, tie-dyed shirt, and get yourself to this special spot. I warn you: don’t come with any expectations. This house is like my grandmother – they lived a vibrant, messy, sexy, fun, full life. We just need to sit back and listen to them and enjoy the epic.

There is nothing simple, straightforward, or easy about history – anyone who tells you that is not listening to this house.

Special Thank You:

National Trust of the United Kingdom: Tony Berry

The Staff at the Sutton House: Chris Cleeve, Sean Curran, Lauren “El Sween”

Cheryl & Mark Wiltshire