As I watched the old building being repainted, I wondered: Are we too quick to erase history in our quest for restoration? Are the peeling paint and the weathered surfaces also part of the building’s story? I question the common practice of stripping old paint layers on historic properties. Each layer represents a moment in time, a choice made by past caretakers. By scraping it all away, are we not scraping away part of the building’s history?

This line of thinking isn’t entirely new. In fact, it harkens back to William Morris and his “Anti-Scrape Society,” formally known as the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which he founded in 1877. Morris advocated for minimal intervention, urging that we should “stave off decay by daily care” rather than attempting to recreate a building’s past glory ( https://www.spab.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/MainSociety/Campaigning/SPAB%20Approach.pdf )

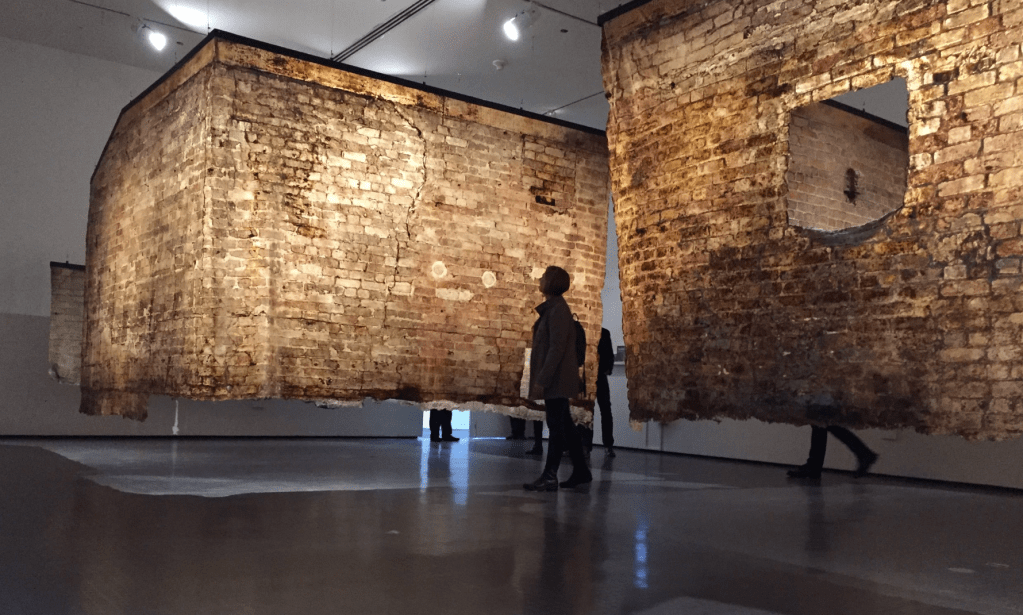

More recently, Jorge Otero-Pailos’ “The Ethics of Dust” series ( https://www.oteropailos.com/the-ethics-of-dust-series#/the-ethics-of-dust-trajans-column/ ) brings this concept into the contemporary art world. In projects like his work at the Doge’s Palace in Venice (2009) or Westminster Hall in London (2016), Otero-Pailos used latex to create casts of accumulated pollution on historic surfaces, preserving and displaying what we typically clean away without a second thought.

But perhaps the most poignant articulation of this perspective comes from an unexpected source: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel “The Beautiful and Damned.” In a passionate monologue, the character Gloria rails against the sanitized preservation of historical sites:

“Trying to preserve a century by keeping its relics up to date is like keeping a dying man alive by stimulants. […] Beautiful things grow to a certain height and then they fail and fade off, breathing out memories as they decay. And just as any period decays in our minds, the things of that period should decay too, and in that way, they’re preserved for a while in the few hearts like mine that react to them.”

Gloria’s words cut to the heart of my feelings as I watch the painters at work. The act of scraping away old paint layers is precisely what she’s criticizing – an attempt to keep a building perpetually young, denying it the dignity of its age and history. When she says, “I want it to smell of magnolias instead of peanuts, and I want my shoes to crunch on the same gravel that Lee’s boots crunched on,” isn’t she expressing a desire for an authentic experience that goes beyond mere visual preservation – and a fresh coat of paint?

As I watch the painter’s work, I can’t help but think about the stories hidden in those old layers of paint. The changing fashions, the economic ups and downs, and the technological advances in paint production are all recorded in those weathered surfaces we’re so quick to cover up. Each scraped-away layer is like a page torn from the building’s biography.

Of course, I recognize the practical concerns. Paint protects buildings, and allowing them to deteriorate isn’t a viable long-term strategy. But perhaps there’s a middle ground—a way to honor both the original design and the building’s journey through time, as Morris suggested and Gloria yearned for.

Maybe it’s time we broadened our view of what’s historically significant in our buildings. Perhaps the peeling paint and worn surfaces aren’t imperfections to be corrected but valuable records of human interaction and the passage of time. How might this shift in perspective change our approach to preserving our architectural heritage?

Can we find a balance that respects the need for preservation and the value of visible history?

As Fitzgerald’s Gloria puts it, “There’s no beauty without poignancy, and there’s no poignancy without the feeling that it’s going, men, names, books, houses—bound for dust—mortal—” In our rush to preserve, are we inadvertently erasing the very mortality that gives these buildings their profound beauty and meaning?