I entered this one-night stand in a state of transition, personally and professionally. I hoped an overnight stay at the Pope Villa would take my mind off my situation and redirect my thinking outward. No such luck.

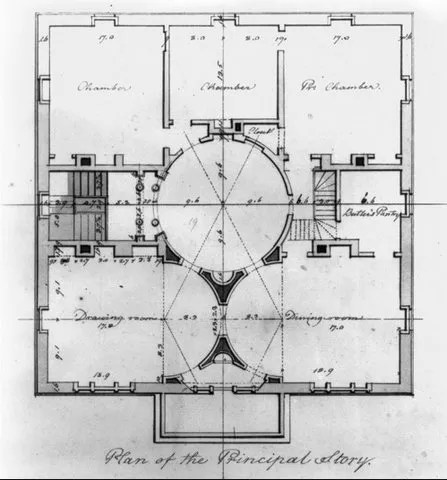

Pope Villa, located in Lexington, Kentucky, was designed in 1811 by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Senator John Pope and his wife Eliza. Completed in 1813, the villa stood as one of Latrobe’s most innovative residential designs until it was severely damaged by fire in 1987. This Federal-era mansion’s unique cubic form and revolutionary central rotunda plan marked a dramatic departure from traditional American house designs of the period. Now owned by the Bluegrass Trust for Historic Preservation, the stabilized ruins of Pope Villa represent one of only three surviving Latrobe residential buildings in the United States.

Standing amidst Pope Villa’s crumbling remains, I was at a personal crossroads, much like our democracy – both of us seeking direction in uncertain times. As my husband Johnny Yeagley and I walked through the weakened walls, he made a striking observation: these ruins, designed by Latrobe to embody democratic ideals, seemed to whisper warnings about the fragility of our civic aspirations, their deterioration eerily echoing recent assaults on another of Latrobe’s masterworks: the U.S. Capitol. In both structures – one a domestic experiment in democratic space, the other the very symbol of our republic – Latrobe’s architectural optimism now stands wounded, forcing us to confront uncomfortable questions about the durability of our democratic ideals and the shadows that have always lurked within our noblest architectural ambitions.

Pope Villa’s rich architectural legacy and current incarnation as a haunting, stabilized ruin commanded my attention. Yet, I struggled to reconcile what I saw with what I knew of its intended purpose — much as I was struggling to reconcile my current circumstances with my previous life plans.

This Federal-era mansion was meant to be more than just a home—it was conceived as a physical manifestation of democratic ideals, a diagram of democracy in architectural form. Yet, as I explored its ruins, I became increasingly aware of how this ambitious design reflected not just aspirational architectural principles but also the complexities of human nature—and, more surprisingly, my personal journey.

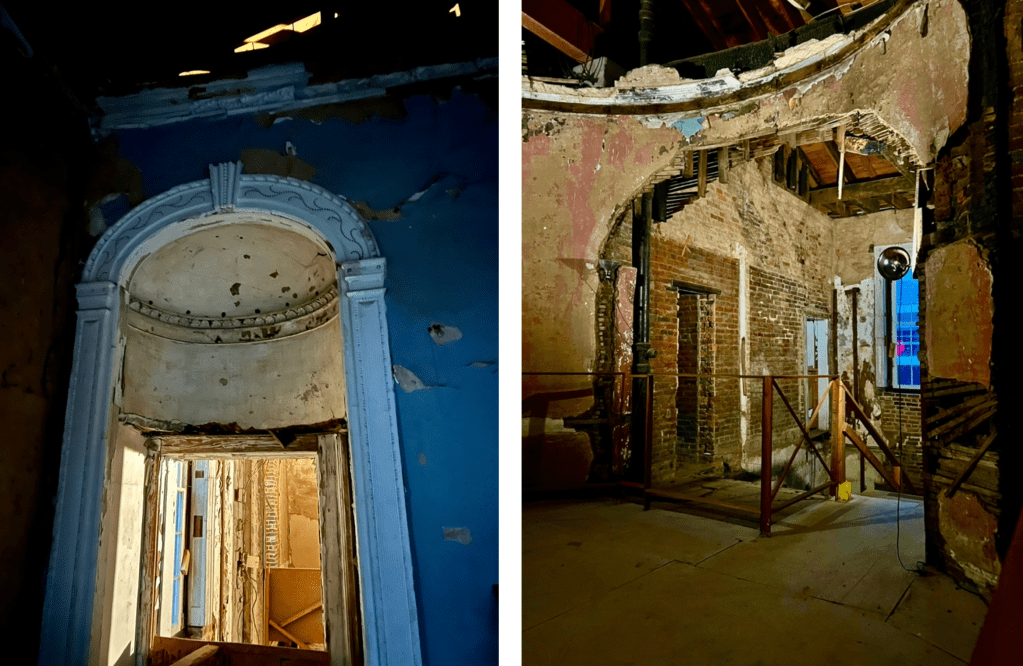

The stark geometries of Pope Villa’s exposed walls, now laid bare by time and decay, spoke of rigid principles and unyielding idealism. As I traced these lines with my eyes, I couldn’t help but think of my life’s carefully laid plans, now exposed and challenged. The play of light through the villa’s fragmented walls created a stark effect, alternately revealing and concealing the silent order, much like the complex interplay of public and private spheres in a democratic society—and our lives. As I moved through the ruins, the sense of a once-private space now open to public scrutiny seemed to mirror the essence of democratic transparency.

At first glance, the villa’s remaining walls impressed me with their bold lines and innovative design. Latrobe’s vision was clear: this was to be a residence that embodied the principles of the young republic, a domestic space that reflected the ideals of equality, transparency, and civic virtue. The central rotunda, now collapsed, must have once stood as the heart of this democratic diagram, a space where family and civic life could seamlessly blend.

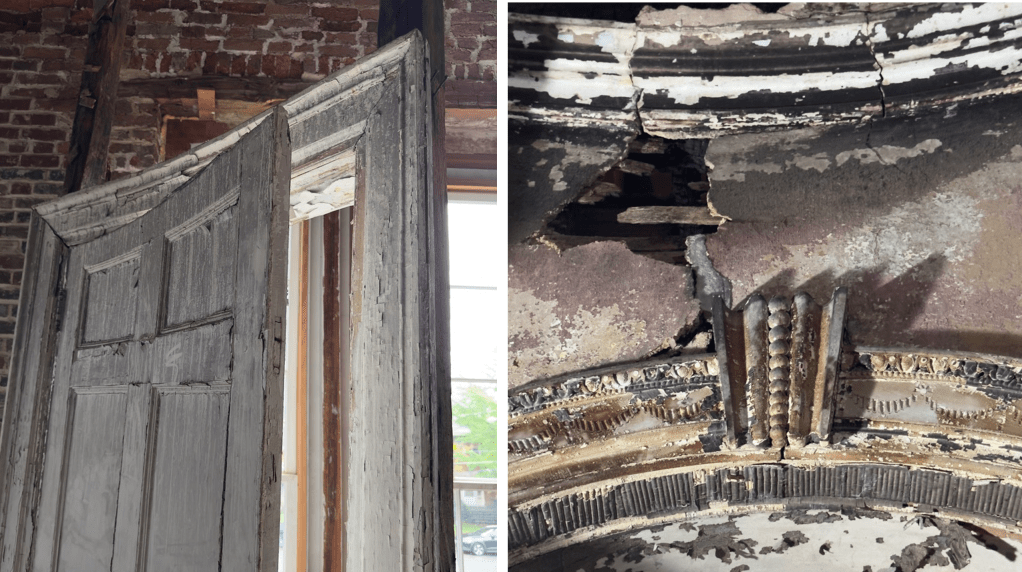

However, as I melted deeper into the ruins, I was struck by an intriguing incongruity: the scale of the villa felt curiously out of sync with its domestic functions. The baseboards stood unusually tall, while the decorative detailing projected a monumentality more befitting a public edifice than a private residence. This oversized ornament created an odd dissonance with the actual dimensions of the building as if the villa was straining to occupy a grander footprint than its physical confines allowed. In this architectural ambition, I saw a reflection of our human tendency to project an idealized image that sometimes surpasses our accurate dimensions.

This tension between scale and function underscored the villa’s unique position in architectural history. In his eagerness to craft a new American architectural language, it seemed as if Latrobe had imbued even the most intimate spaces with civic grandeur. The result was a domestic setting that, I felt, never allowed its inhabitants to forget their place in the larger national narrative. But how, I wondered, did this constant reminder of civic duty impact the daily lives of those who called Pope Villa home?

As I lay in my makeshift bed for this “one-night stand”, I visually explored the layers of Pope Villa’s fire-damaged bedroom chamber, my focus shifted to the minds behind its creation: Benjamin Latrobe, certainly, but also Senator John Pope and his fashionable English wife, Eliza. This Kentucky power couple had commissioned a home that showcased their progressive tastes and avant-garde aspirations. However, this architectural choice came with risks. As tensions with England escalated and the War of 1812 approached, the Villa’s innovative design—influenced by Eliza’s British background and Latrobe’s European training—threatened to appear too “British” for a Kentucky politician with national ambitions.

This realization added yet another layer of complexity to Pope Villa’s identity. Not only was it a bold departure from contemporary Southern American residential norms, but it also stood as a crucial stepping stone in the evolution of American architecture. The villa’s innovative design elements—its central rotunda, unconventional floor plan, and novel use of light—were more than mere aesthetic choices. They were calculated experiments, each informing Latrobe’s vision for the monumental buildings that would come to symbolize American democracy.

Yet, as I continued my mental exploration, I became increasingly preoccupied with a singular question: how did one live in this “diagram of democracy”?

The villa’s innovative public/private bifurcation, once a point of pride, now revealed itself as a complex experiment in social engineering. The ruins exposed the intricate network of spaces designed to keep the enslaved out of sight while maintaining the illusion of an egalitarian household. This revelation highlighted how architectural innovations, even when well-intentioned, can sometimes reinforce societal inequalities rather than resolve them—a sobering reflection of how our ideals can sometimes clash with our realities.

Standing in what was once the heart of the home, I was struck by how the ruins revealed the villa’s attempt to balance multiple, often conflicting ideas. It tried to be a showcase of European sophistication, a laboratory for a new American architecture, a statement of democratic ideals, and a functional family home—all while hiding the harsh realities of slavery within its walls. The decayed state of the villa now laid bare these contradictions, revealing the challenges of inhabiting a space so burdened with ideological weight.

The very internal organization of Pope Villa, with its innovative public/private bifurcation, inadvertently highlighted the deep societal divisions it sought to obscure. The in-between spaces and marginal placements of servant quarters within the house’s formal, public cubic box spoke volumes about the era’s attempts to reconcile high-minded ideals with the brutal practice of human bondage. How, I wondered, did the Popes navigate this architectural manifestation of their society’s deepest contradictions?

These architectural choices revealed a disturbing strategy: to render the enslaved individuals who made the Popes’ lifestyle possible as invisible as architecture would allow. The stark separation between the public areas and the slave-filled servant spaces further emphasized this troubling dynamic, making me question how one could genuinely inhabit a “diagram of democracy” built on such fundamental contradictions. Did the Popes feel the weight of this irony as they moved through their home, or did Latrobe’s clever design allow them to ignore this uncomfortable truth?

In this light, Pope Villa became a physical manifestation of this cognitive dissonance. Its clean lines and revolutionary spaces, designed to showcase a new American aesthetic, simultaneously worked to camouflage the ugly truth of slavery. Latrobe and the Popes, in their pursuit of architectural innovation, seemed to treat the issue of slavery and servitude as an inconvenient reality to be absorbed into an undefinable ether of negligibly discernible forms. But could such a reality be hidden, even in the most ingeniously designed home?

As I continued my exploration, I found myself continually reintroduced to the remains of the villa’s ambitious central rotunda, Latrobe’s artistic centerpiece. In its decayed state, it stood as a poignant reminder of the risks ambitious aspirations which can catastrophically fail to materialize. The rotunda, which must have once impressed visitors with its grandeur, now seemed to caution against losing sight of the human scale in pursuing ideological statements. How, I wondered, did the Popes and their guests experience this space? Did its imposing geometry inspire lofty thoughts of civic virtue, or did it simply make everyday interactions feel overwrought and performative?

This careful separation of public and private spaces, now laid bare by decay, revealed the complex social choreography required to maintain the illusion of effortless democracy within the home. In exposing these hidden mechanisms, the villa revealed how spatial arrangements can shape social interactions, for better or worse. Did the inhabitants of Pope Villa feel liberated by these Euclidian spaces or constrained by their implicit rules and social expectations?

As the day wore on and shadows lengthened across the ruins, I reflected on the villa’s story as revealed, not through its diagram but through its decay. In its ruined state, Pope Villa offered a unique perspective on the limits of idealism, providing insights that might have remained hidden had the building survived intact. Once cutting-edge, the villa’s innovative design elements now seemed to express a rueful wisdom. The ruins appeared to caution not against innovation itself but against the uncritical pursuit of architectural ideals at the expense of livability and ethical consistency.

Latrobe’s design for Pope Villa represented a significant departure from colonial American domestic architecture, particularly in treating servant spaces. Traditionally, these areas were often relegated to an “L”-shaped wing attached to the main house—a feature Latrobe vehemently disliked. His aversion to this common layout revealed much about his architectural vision and the societal tensions he wrestled with in his work.

By absorbing the servant functions into the main block of Pope Villa, Latrobe attempted to resolve multiple challenges simultaneously. On one level, he sought to create a more cohesive, geometrically pure form that aligned with his vision of a new American architecture. This approach allowed him to manifest the ideals of egalitarian democracy in built form, at least superficially. However, this design choice also served a more complex—and potentially problematic—purpose. Latrobe effectively veiled the underlying social hierarchy that the traditional “L” wing made explicit by obscuring the clear delineation between servant and served spaces.

This subtle obfuscation of the household’s actual functional and social dynamics presented Latrobe with a significant challenge: maintaining the necessary separation and functionality within a unified architectural form while still projecting an image of democratic ideals. The resulting design, with its ingenious use of in-between spaces and carefully placed servant areas, reflected this intricate balancing act. I couldn’t help but wonder: did this architectural sleight of hand genuinely serve the cause of democracy, or did it simply allow its inhabitants to ignore the contradictions at the heart of their society?

As the sun began to set on my “one-night stand” with Pope Villa, casting long shadows across the ruins, I reflected not just on the villa’s place in the larger narrative of American architecture but on my life’s unexpected deformations.

Just as Pope Villa stood as a bold experiment in creating a uniquely American architectural language, I, too, found myself amid an experiment – not of my own design, but one thrust upon me by life’s unpredictable nature. The villa’s ruins offered a more nuanced perspective on the endeavor of reinvention, revealing both the triumphs and the contradictions of such ambitious transformations.

The villa’s decay revealed the challenges inherent in trying to forge a new identity, whether in architecture or life. Its ruins highlighted the difficulties of balancing innovation with functionality, ambitious dreams with practical needs, and imported ideas with local realities. In its proportions and details, I could read my struggle to reconcile my private self with public expectations, my local commitments with broader responsibilities, and the comfort of familiar routines with the gravitas of a life taking on new, unexpected dimensions.

As I prepared to leave the site, I took one last walk through Pope Villa. In its ruined form, stripped of pretense and exposed to the elements, the villa offered an unexpected opportunity for reflection and learning that paralleled my journey. Just as Pope Villa in decay presented its successes and failures not as endpoints but as valuable lessons, I realized that my own period of deconstruction and reconstruction was not a failure of my original life plan but a valuable process of growth and discovery – where does one go from here?

The villa’s ruins stood as a testament to the power of honest evaluation in architecture and life. In its decayed state, Pope Villa revealed truths about the process of identity-building and the role of our crafted environments in shaping who we are—truths that would have remained hidden had it survived intact.

I couldn’t help but feel reluctantly grateful for the villa’s revelations and the timing of this visit. In laying bare its triumphs and missteps, Pope Villa in ruins offered a profound meditation on the complexities of inhabiting a space – or a life – designed to embody conceptual ideals. The lessons whispered by these weathered boards resonated deeply with my current struggles: the importance of aligning our aspirations with our lived values, considering the full human cost of our personal reinventions, and remaining vigilant against the temptation to obscure uncomfortable truths about ourselves.

Pope Villa had become more than just a relic of the past – it had become a mirror, reflecting my aspirations, contradictions, and hidden truths. It challenged me to look deeper and think more critically about the life I was building, the ideals I professed, and the often-messy reality of trying to live up to those ideals in my daily existence.

As I turned to leave Pope Villa’s charred remains, I felt a complex mix of emotions. There was a sense of unfulfilled expectation – I had approached these ruins hoping to uncover some profound architectural truth, yet found myself struggling with personal revelations instead. The villa’s innovative diagram of democracy that I had so eagerly anticipated exploring had not yielded the insights I craved about architecture but offered unexpected parallels to my own life’s design.

What resonated most as I departed was not Latrobe’s grand design or the villa’s place in architectural history but the shadows it cast – both literal and figurative. These shadows, stretching across the decaying floors and seeping from the spaces between walls, seemed to embody the unspoken narratives and contradictions that my idealistic life plan sought to obscure. In the villa’s awkward in-between spaces, now exposed by decay, I saw reflections of my own uncomfortable yet potent state of transition.

As I shut the heavy front door of Pope Villa, I felt a certain calm wash over me, tinged with melancholy for what was left behind – both in the villa and in my own life. Yet surpassing that sadness was a landscape of potential and new experiences stretching out before me.

I left with the realization that, like Pope Villa, the true significance of my life might not lie in its original ambitious design but in the exposed questions and stories that surrounded it. As I walked away, I carried with me not the enlightenment I had initially sought but a quiet resignation of the complexities that no ingenious plan could fully capture or resolve.

The villa had not provided miraculous answers or a clear path forward. Instead, it had deepened my contemplation on the mystery of transformation—architectural, societal, and personal. I found myself understanding that, like the villa, I, too, was being deconstructed, my in-between life now made public. It was awkward and sometimes uncomfortable, yet as I left my old self behind, I felt not just sadness but confusion about the new experiences that awaited me.

In the end, Pope Villa’s greatest gift was not as an exemplar of Federal-era architecture or as a laboratory for a new American style. For me personally, its value lay in its ability to reveal the gulf between idealism and lived reality –

The door closed behind me, and unlike Pope Villa, I didn’t have a diagram to orchestrate my next move.

Special thanks to The Blue Grass Trust (Jonathan Coleman). Daniel Ackermann

Read Twisted Preservation’s latest article, “One Night Stand: Living in the Shadows of a Diagram,” for intriguing insights and unique perspectives.

LikeLike