Like a person, a neighborhood carries the weight of its history in its name – a linguistic fossil that can outlive its original meaning. The Meatpacking District is now a paradox: a place defined by an industry that will soon be completely absent from its streets. This phenomenon creates what we might call a “nomenclature ghost” – where the signifier remains but the signified has vanished, like a shadow without its object.

This dilemma mirrors our personal struggles with identity through time. When a lawyer who once dreamed of being a poet introduces themselves, are they still that aspiring poet inside? When a former athlete becomes a business executive, do they shed their athletic identity like a snake’s old skin, or does it remain as an integral layer of their being? Our titles and roles – student, parent, professional – accumulate like geological strata, each layer informing but not erasing what came before.

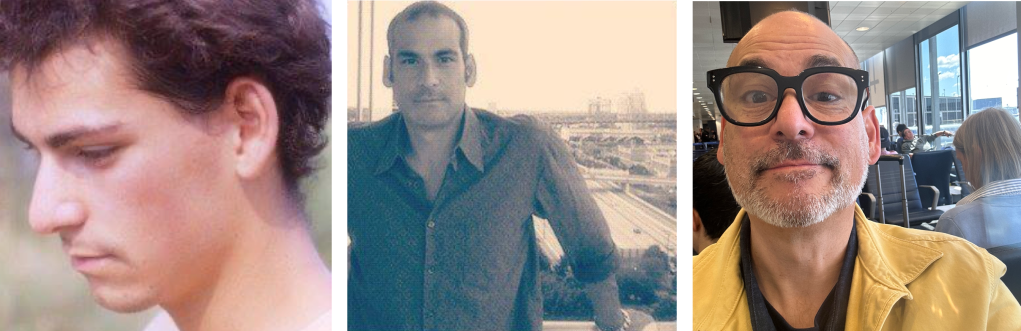

The mirror presents a daily paradox. In my mind’s eye, I can still see that young man with abundant hair and a metabolism that could forgive any indulgence. Growing up in the South, I moved through the world wrapped in the invisible cloak of cultural privilege, completely unaware of how this unseen advantage smoothed certain paths while my internal reality as a queer person simultaneously pushed me toward the margins. This early experience of existing in the space between appearance and authenticity created its own kind of cognitive dissonance – my outward presentation conferring unearned advantages even as my authentic self remained carefully hidden from view.

The social worlds I inhabited existed in the borderlands between dominant and non-dominant cultures, creating a rich tapestry of understanding that would have been impossible from a position of unexamined privilege alone. Like the Meatpacking District, whose industrial façades now house entirely different realities, I too contained multitudes that weren’t immediately visible to the casual observer.

The body I inhabit now bears the signatures of decades: thinning hair, slower recoveries, the need for reading glasses that somehow keep migrating to forgotten locations throughout the house. Yet this transformed vessel carries not just physical changes but a profound shift in responsibilities. Where once I was the one being cared for, I now find myself in the complex dual role of caring for aging parents – those who once tied my shoes and cleaned my scraped knees – while also nurturing and protecting new life. The energy that once felt bottomless now requires careful stewardship, like a finite resource that must be mindfully allocated.

What describes me now is perhaps best captured not by physical attributes or singular roles, but by this capacity to span time – to hold simultaneously the memory of being cared for and the active responsibility of caring for others. The privilege I once moved through the world unaware of has become a tool I can consciously deploy in service of others, while my experience of otherness helps inform a more compassionate and nuanced approach to understanding different lived experiences.

The desire to preserve a specific moment in time – whether through maintaining a historical district’s name or through cosmetic surgery – reflects a deeply human impulse to arrest change. But this impulse often conflicts with the organic nature of both urban and human development. Just as my own narrative couldn’t be fully understood through surface-level observation, the rich histories of places and communities resist simple categorization or single-story interpretation.

Public history, as a discipline, often struggels with this tension between preservation and evolution. When we designate a historic district or landmark, we’re essentially drawing a circle around a moment in time and saying “this matters.” But in doing so, we risk creating a kind of historical taxidermy – preserving the outer form while the inner life has moved on. The Meatpacking District’s transformation from an industrial hub to a fashionable neighborhood reveals the limitations of this approach.

Perhaps a more nuanced approach to public history would acknowledge that change itself is part of the historical narrative. Rather than trying to freeze neighborhoods or buildings in amber, we might embrace their evolution as part of their story. This would mean moving beyond the traditional model of historical interpretation that focuses on a single “period of significance” to one that recognizes the value of layered histories and ongoing transformation.

Like historic places that carry multiple layers of meaning and significance, we too contain multitudes, our identities shaped not just by time’s passage but by the complex interplay of how we are seen and who we know ourselves to be. The young man I was doesn’t need to be gone for the person I am to exist. Rather, he is a crucial chapter in an ongoing story, one that continues to unfold with each passing day. The chasm between perception and reality, between privilege and marginalization, between past and present selves, isn’t just a void to be bridged – it’s a space where meaningful understanding can grow.

The profession of public history might thus evolve to become less about preserving specific moments in time and more about documenting and facilitating the dialogue between past and present, acknowledging that every historic place, like every person, is not just what it was, but what it is becoming. The challenge lies in maintaining a connection to history without becoming its prisoner – allowing places and people to grow and evolve while keeping their stories alive.