The act of remembering is never neutral. As I’ve watched different cultures and institutions create monuments to commemorate historical violence and genocide, I’ve found myself increasingly troubled by the underlying dynamics at play. There seems to be an unspoken assumption that memorialization somehow balances the scales of history – as if acknowledging past wrongs through bronze and stone could make them right.

In my observation, these permanent monuments often serve less as authentic vehicles of remembrance and more as tools for controlling historical narratives. When the same power structures that enacted historical violence control how that violence is remembered, we risk creating what feels to me like a form of collective gaslighting – where the performance of remembrance becomes more critical than genuine reconciliation or change.

As I’ve contemplated these monuments and memorials, I’ve become increasingly aware of how power shapes what we remember and how we remember it. The official commemoration seems to channel memory through specific cultural filters, often overwhelming and replacing the lived experiences of affected communities. When those who hold power get to determine the “official” version of history through their monuments, what voices are we losing? What memories are being overwritten?

Across Europe, I’ve encountered powerful alternatives to traditional memorialization that have shaped my thinking about these questions. In Budapest’s Memento Park (Szoborpark), the massive Socialist monuments of Hungary’s communist era stand in exile. Rather than destroying these ideologically charged statues after the fall of communism or allowing them to maintain their positions of authority throughout the city, they were gathered and deliberately displaced into what amounts to a statue graveyard on the outskirts of the city. This act of preservation through displacement creates a fascinating tension – the statues remain as historical artifacts but are stripped of their original power and purpose. By removing them from their pedestals of authority and gathering them in this almost satirical setting, the park transforms what were once symbols of oppression into objects of reflection and even subtle ridicule.

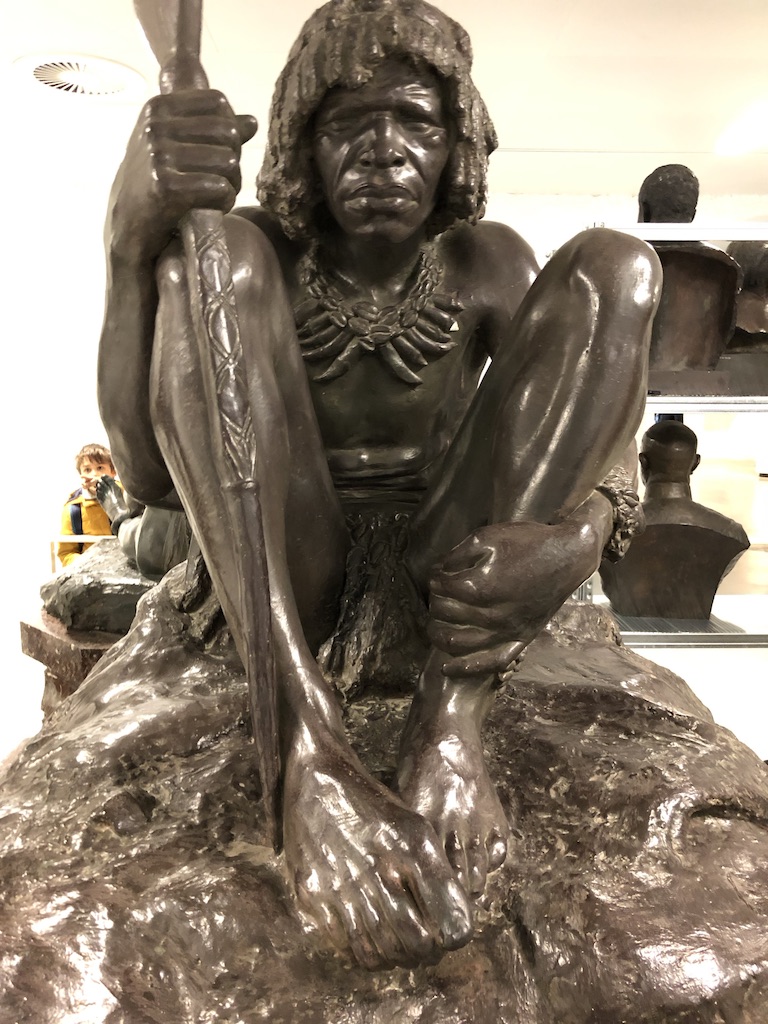

A more direct confrontation with problematic commemoration can be found at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (now AfricaMuseum) in Tervuren, Belgium. Here, the very same triumphant bronze sculptures and elaborate dioramas that once celebrated Belgium’s colonial “civilizing mission” in Congo now serve as damning evidence of colonial violence and racist ideology. Rather than removing these troubling artifacts, the museum has reframed them, surrounding them with new interpretative materials that expose their original propagandistic intent. The infamous gilded statue showing a Belgian “bringing civilization” to a Congolese child remains but now exists as a specimen of colonial arrogance rather than an object of admiration. This approach creates a powerful cognitive dissonance – forcing visitors to simultaneously see both the intended message of these monuments and their proper historical significance as tools of oppression.

In America, the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, offers perhaps the most moving example of how humble materials can carry immense memorial weight. Their soil collection project uses nothing more valuable than earth gathered from lynching sites across America, preserved in glass jars. Each jar contains perhaps the most common and overlooked of materials, yet this soil holds within it the last physical connection to these acts of violence and their victims. Named, dated, and carefully preserved, these jars of earth become powerful transmitters of memory, their very ordinariness making them all the more affecting. The power lies not in the permanence or grandeur of the material but in its direct connection to the event being remembered. These jars of soil also speak to the impermanence of memory – the soil can be scattered, mixed, and transformed – yet paradoxically, this impermanence makes them more truthful as carriers of historical memory than imposing bronze or marble monuments.

The artist Jorge Otero-Pailos’s “Ethics of Dust” series offers another compelling approach to what we might call anti-honorific memorialization. By carefully removing centuries of accumulated pollution and grime from historical buildings and preserving these extracted layers as independent artifacts, he creates what amounts to negative impressions of history – literal shadows of time’s passage. These delicate latex sheets of preserved dust and debris tell stories not of grand historical moments or influential figures but of daily life, industrial development, and environmental change. Like the soil collections in Montgomery, these dust extractions elevate the overlooked and seemingly worthless into powerful carriers of memory. They suggest that perhaps the true story of a place lives not in its carefully maintained facades but in the accumulated grime of everyday existence – the residue of countless forgotten moments and anonymous lives. This approach inverts traditional monumentality: rather than adding something grand and permanent to a space, it preserves what time itself has deposited, making visible the usually invisible processes of decay and transformation.

These various approaches to memorial-making – from the displaced monuments of Memento Park to the recontextualized colonial artifacts in Belgium, from the profound simplicity of collected soil in Montgomery to the preserved dust of everyday life – have profoundly influenced my artistic practice. Rather than contributing to the tradition of permanent monuments, I’ve created what I call “transient monuments” – works that deliberately embrace their own impermanence. Using detritus and disposable materials as my medium, much like the humble soil of Montgomery or Otero-Pailos’s extracted histories, I aim to create memorials that can shift, deteriorate, and transform, mirroring how our understanding of history evolves.

My “Life Museum” project emerged from this thinking about constructing and reconstructing memory. Instead of presenting a fixed narrative, these installations allow for constant rearrangement and reinterpretation. How elements can be reconfigured mirrors how our understanding of historical figures and events evolves. By using found objects and society’s cast-offs, I’m suggesting that our collective memory is built from what we choose to remember and what we’ve decided to forget or discard.

In my transient, kinetic monument projects, like the ones pictured here, I explore how revealing and concealing can become part of the memorial experience. The piece consists of a simple wooden cabinet mounted on a utilitarian stepladder – both found objects that carry their own histories of use and discard. Inside, fragments of domestic life are glimpsed through an intentionally restricted viewing experience, forcing the viewer to physically engage with the piece to access its contents. This interaction becomes a metaphor for how we engage with memory – partial, fragmentary, requiring effort and involvement. The motion of discovering what lies within mirrors our own process of uncovering historical truths, while the humble materials – the worn wood, the everyday objects, the makeshift display – resist the monumentality typically associated with memorial-making. Like the soil collections in Montgomery or Otero-Pailos’s preserved dust, these pieces elevate the overlooked and ordinary into memory carriers. But they go further by making remembering itself a physical, time-based experience. The viewer becomes a witness and participant, their movement and engagement essential to the piece’s meaning. This approach suggests that memory isn’t something to be passively received from an imposing monument but rather something we must actively work to uncover and understand.

Through this work, I’m not just questioning traditional forms of memorialization – I’m trying to imagine new ways of engaging with our collective past. Perhaps accurate remembrance isn’t about creating permanent markers that resist time and change but embracing the inherently transient nature of memory and understanding. By acknowledging this impermanence in the physical form of our memorials, we might come closer to honest engagement with history.

The challenge isn’t just about creating new forms of memorials but about fundamentally rethinking our relationship with historical memory. Through Public History-informed sculptural work, I’m exploring the possibility that meaningful remembrance requires us to embrace uncertainty and change rather than trying to fix memory permanently in place. In this way, the physical transformation of these pieces becomes a metaphor for the transformation of understanding itself – always in flux, always open to reinterpretation, always alive with the possibility of new meaning.

One thought on “The Disposable Monument: Finding Truth in Transient Memory”