In my work as a public historian, I’ve repeatedly returned to four fundamental frameworks that have shaped my understanding of how landscapes, monuments, and cultural memory intersect: Simon Schama’s insights into landscape meaning, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s architectural theory, John Hejduk’s architectural narratives, and contemporary approaches to monumentality. These intersections reveal new ways of commemorating the past while acknowledging memory’s fluid nature.

Schama’s “Landscape and Memory” (Knopf, 1995) transformed my understanding of how landscapes accumulate layers of cultural meaning over time. His work reveals that these meanings aren’t fixed but evolve as societies reinterpret their relationships with particular spaces. I see this evolution constantly in my work – a forest or river that once held sacred significance becomes a symbol of national identity, industrial progress, and environmental concern. This fluidity of meaning now shapes everything I do with cultural landscapes.

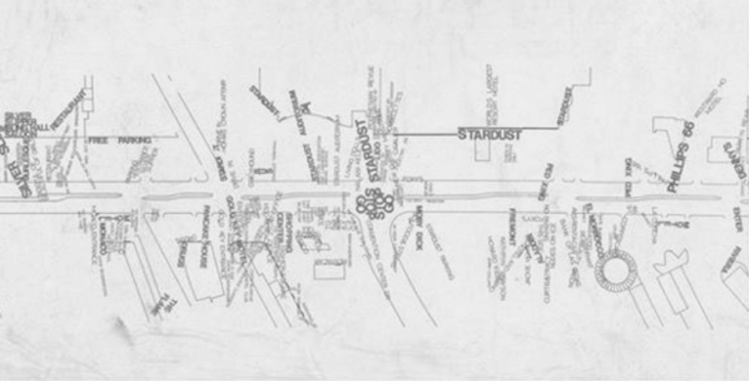

Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour’s “Learning from Las Vegas” (MIT Press, 1972) provides equally vital insights. Their analysis of how built environments function as systems of signs and symbols illuminates how interventions in the landscape – whether commercial signs or public monuments – function as what they termed “billboards to meaning.” They showed me how physical spaces can be intentionally designed to convey particular messages.

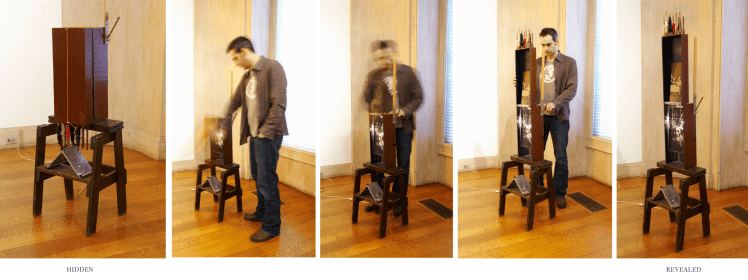

John Hejduk’s “Mask of Medusa” (Rizzoli, 1985) offers another crucial perspective on how landscapes and structures carry meaning. Through his concept of “masques” – architectural characters between reality and imagination – Hejduk demonstrates how physical spaces can simultaneously embody stories, memories, and transformations. His work suggests that landscapes, like his architectural characters, are never simply physical entities but are constantly engaged in a theatrical performance of memory and meaning. This understanding of landscape as both a physical presence and narrative device helps explain how places can simultaneously preserve the past while remaining alive in the present.

Yet in “The Disposable Monument: Finding Truth in Transient Memory” (2024), I argued that traditional approaches to monumentality often control historical narratives rather than facilitate genuine remembrance. Like Hejduk’s masques, which resist fixed interpretation in favor of ongoing performance of meaning, monuments, and landscapes might better serve memory by acknowledging their role as actors in an ongoing narrative rather than fixed symbols of the past.

My work with transient monuments attempts to develop alternatives that align with both Schama’s understanding of fluid landscape meaning and Hejduk’s conception of architecture as temporal performance. By embracing impermanence, these monuments make visible what Schama shows happens naturally – the evolution of meaning over time. Just as Hejduk’s architectural characters perform different roles depending on their context, projects like the soil collection at the Legacy Museum in Montgomery or Jorge Otero-Pailos’s “Ethics of Dust” series demonstrate how ephemeral materials become powerful carriers of memory precisely because they acknowledge their own impermanence.

The recontextualization of monuments at Budapest’s Memento Park or Belgium’s Africa Museum offers another strategy for working with meaning’s fluid nature. These spaces become what Hejduk might recognize as stages for his masques – places where meanings perform and transform through changing contexts rather than remaining fixed in stone.

This understanding of fluid meaning becomes particularly relevant when considering how landscapes change over time. The life cycles of trees and other landscape features mirror Hejduk’s interest in transformation and temporality – both experience growth, maturity, decline, and regeneration. Traditional preservation practice often calls for like-kind replacement when historic trees die, or landscape features deteriorate. This approach offers continuity and comfort, providing communities with tangible connections to their past. Many find deep meaning in seeing “the same” tree species growing where their ancestors walked.

However, these moments of landscape transition also present opportunities for deeper community engagement with place and meaning. Rather than viewing preservation choices as binary – either traditional replacement or contemporary reinterpretation – we can embrace multiple approaches that allow landscapes to carry both historical and emerging meanings. Like Hejduk’s masques, these spaces can perform multiple roles simultaneously.

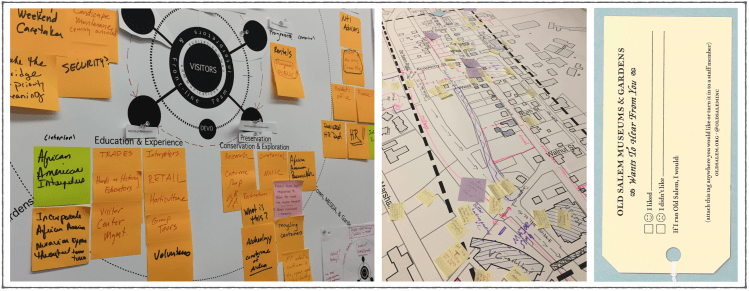

Community design charrettes around landscape changes can become powerful tools for collective memory-making. Alongside traditional preservation approaches, we can create space for temporary installations that help people process and reflect on landscape change. These “anti-monuments” or temporal landscape interventions might include artists working with fallen limbs to create temporary sculptures, community documentation projects capturing stories about dying trees, seasonal installations marking transitions between old and new plantings, or interactive elements inviting people to share their memories and hopes for the space. Each approach echoes Hejduk’s understanding of architecture as a form of storytelling, where physical forms become characters in an ongoing narrative of place.

Through practice, I’ve developed these core principles for working with evolving landscapes:

- Design commemorative spaces that can accommodate both permanent and temporary interventions

- Use ephemeral materials and installations to highlight the dynamic nature of landscape meaning

- Create opportunities for community engagement in interpretation and design

- Develop frameworks that acknowledge multiple, layered meanings

- Embrace change as an opportunity for renewed community connection with the place

This dual approach—honoring traditional preservation while creating space for temporal interpretation—reflects how landscapes function in our lives. Like Hejduk’s architectural characters, they are simultaneously physical and narrative, historic and contemporary, fixed and fluid, personal and communal. By embracing both permanent and temporary interventions, we allow communities to engage with landscapes as living, evolving spaces rather than just historical artifacts.

The convergence of Schama’s insights about landscape meaning, Venturi and Scott Brown’s ideas about architectural communication, Hejduk’s concepts of architectural performance, and contemporary approaches to transient monuments opens rich new directions for public history. When we acknowledge landscapes as both carriers of historical memory and performers of ongoing meaning-making, we create opportunities for more authentic and inclusive forms of preservation practice.

Our challenge as public historians extends beyond creating new forms of monuments to fundamentally rethinking our relationship with historical memory in public spaces. By embracing multiple landscape preservation and interpretation approaches, we can create spaces that honor continuity and change, allowing communities to engage more deeply with their shared environments. This approach moves us beyond traditional monumentality toward a more dynamic and honest form of public commemoration that recognizes landscapes as creations of the past and living elements of contemporary community life.