The morning unfolded through spaces both intimate and shared. Jaxson raced across the playground, confident and free, before we settled on a park bench to watch the world pass by. Elderly couples ambled past, teenagers laughed in clusters, and families hurried to weekend activities – each group writing their own momentary story across the public green. Later, tucked into a quiet corner of the bakery, we shared a doughnut and dove into his new fascination with rockets, the pages of his fresh book from Charter Bookstore spread between us.

Each transition revealed new facets of Jaxson—from confident explorer on playground equipment to curious observer of strangers passing by, eager scholar picking out a book about rockets, and animated storyteller over our shared doughnut. As his grandfather, I treasured each moment. As a public historian, I saw how these seemingly ordinary shifts in space and interaction exemplify the subtle rhythms we so often fail to document.

The Swedenborgian concept of “continuous and discrete degrees” offers a valuable framework for understanding these subtle shifts. It suggests that change occurs constantly but in such minute increments that we only recognize the transformation once it becomes unmistakable – like watching a child grow. You notice it suddenly one morning, though the change has been continuous. In public history, we often miss these continuous degrees of change, instead focusing on discrete moments that seem more historically significant. Yet it’s in these small, continuous changes – like my grandson’s shifting engagement with space throughout our morning – where we find the true texture of human experience.

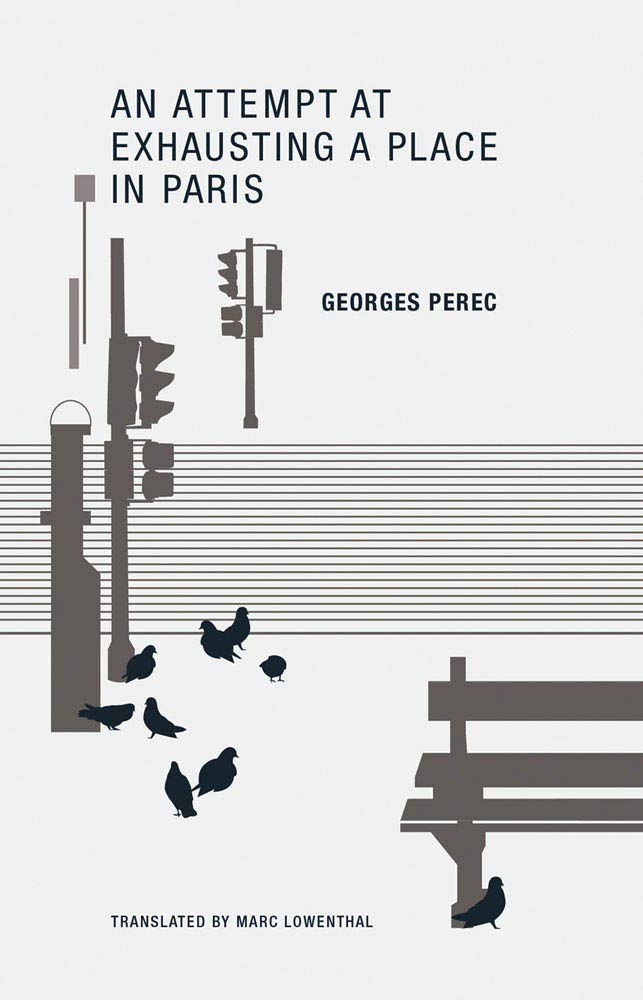

Michel de Certeau’s “The Practice of Everyday Life” (1980) explores this tension by examining how ordinary people’s daily routines constitute forms of meaning-making often overlooked by traditional historical narratives. Similarly, Carlo Ginzburg’s microhistorical approach in “The Cheese and the Worms” demonstrates how examining seemingly insignificant lives reveals deeper cultural patterns. Georges Perec’s “An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris” (1975) takes this further – through meticulous documentation of mundane details like passing buses and pigeons at Place Saint-Sulpice, he reveals how richly textured ordinary public spaces become when we truly pay attention. Yet despite these theoretical frameworks, we still mythologize “periods of significance,” freezing historic spaces – particularly homes – in supposedly meaningful moments while ignoring life’s continuous flow.

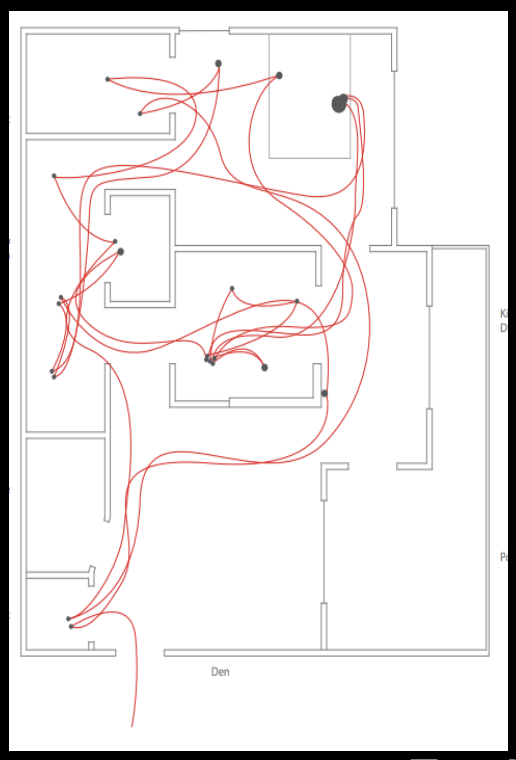

I’ve studied how rooms in homes organically evolve as families adapt them to their needs. A nursery becomes a teenager’s room, then a home office, then a guest room – each transformation carrying its own significance. Henri Lefebvre’s “The Production of Space” (1974) helps us understand how such spaces are socially produced through daily use. Yet, our current interpretive frameworks, focused on dramatic events and notable figures, struggle to capture these quieter aspects of history.

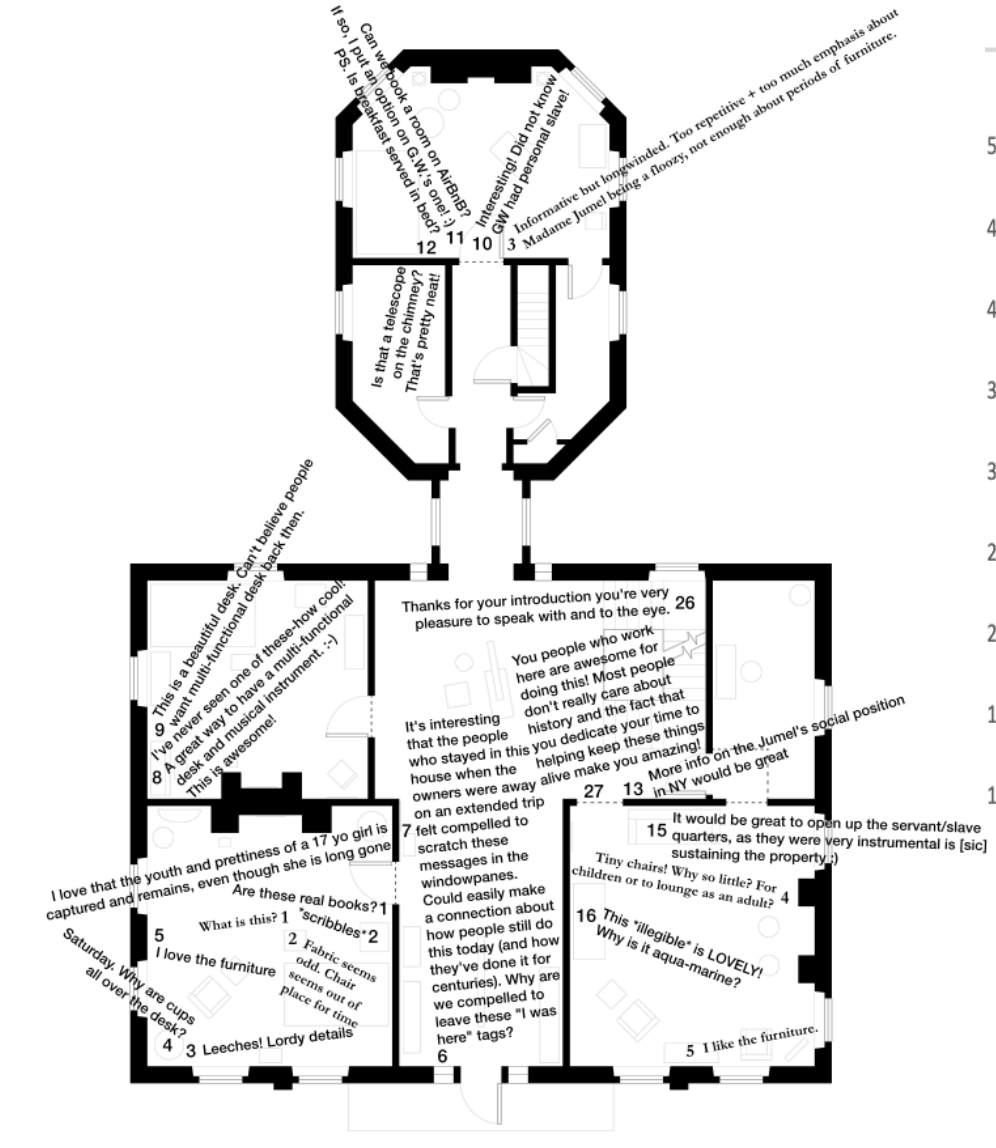

When we designate a period of significance, we arbitrarily decide which historical layer matters most. Collection policies, restoration decisions, and interpretive narratives become confined within these artificial temporal boundaries, stripping away the rich patina of lived experience that makes spaces meaningful. Just as my morning with my grandson moved between private intimacy and public space, historic sites accumulate countless such layers of meaning through generations of use. Our challenge as public historians lies in developing new methods to capture and convey these seemingly insignificant moments that ultimately shape both our personal spaces and our broader historical understanding.