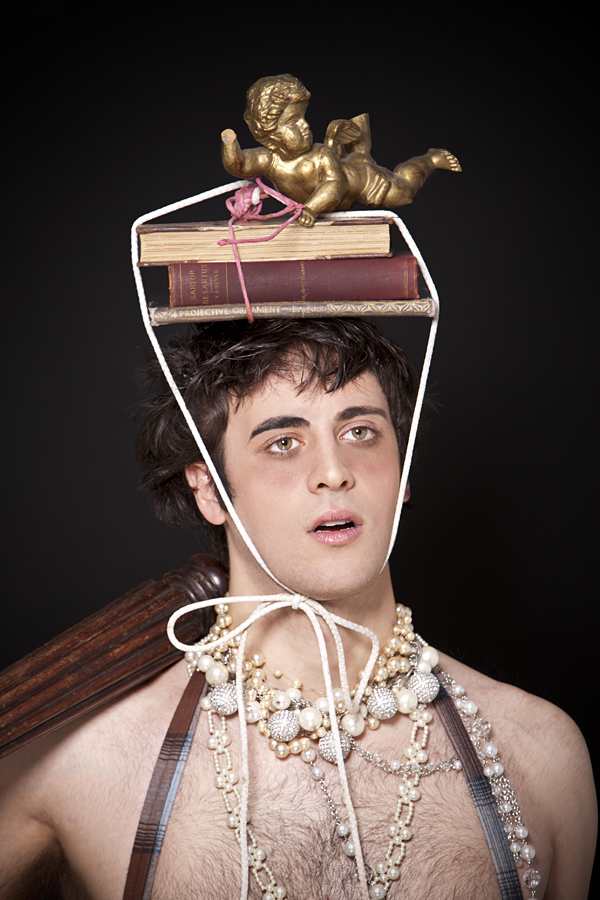

“Pretty things, so what if I like pretty things” Pretty Things, Rufus Wainwright

As a museum professional and public historian with over two decades of experience in collections care and archive organization, I’ve witnessed firsthand how our relationship with cultural heritage materials evolves. My career has focused on creating unified, accessible collections from dispersed materials – from establishing the Raymond & Mildred Pitcairn Archives at Glencairn Museum to establishing the Bryn Athyn Cathedral Archive to unifying documents for the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks’ formation. While at the Historic House Trust of New York City, I participated in collection and archive-related decisions and oversight for documents and archaeological artifacts across all 23 historic sites, with most heritage sites maintaining their own archives on-site. At Old Salem, I helped consolidate artifacts and documents into a single archive venue, enhancing storage conditions and accessibility. Most recently, at NRF, I was part of the team that gathered the collection of scattered materials into one location and hired their first professional archivist.

These experiences bringing together disparate collections have taught me that preservation isn’t just about loving pretty things—it’s about understanding their context and ensuring their relevance for future generations.

Rufus Wainwright’s meditation on beauty and impermanence captures a profound truth about our relationship with material culture. His lyrics acknowledge our attraction to beautiful objects while confronting their ephemeral nature – “This time will pass and with it will me/And all these pretty things.” As a preservationist, I live with similar tensions: the desire to preserve beautiful and meaningful objects, even as we recognize that relationships with material culture inevitably shift and transform across time and space.

Like the astronomical distances Wainwright invokes in his song (“From where you are/To where I am now/Is its own galaxy”), we find ourselves at a fascinating distance from traditional approaches to preservation and collections care. We can look back at these practices while charting a new course forward, acknowledging both our love of beautiful things and the complex realities of maintaining them.

Traditionally, museum conservation followed the “everything is a Rembrandt” approach – treating each object with the highest possible preservation standards, regardless of context or resources. While this reverence for material culture came from a good place, it’s increasingly clear that this approach isn’t sustainable or desirable today.

We’re witnessing this shift dramatically in the current generational transition. As Baby Boomers downsize, we see a fascinating and sometimes painful phenomenon: their children and grandchildren often cannot or do not want to take on the responsibility of preserving the life objects collected by previous generations. This isn’t simply about different tastes or values – it reflects profound changes in how younger generations live and relate to material culture.

Multiple factors drive this shift. There’s the digital transformation, where memories and experiences are increasingly stored in clouds rather than cabinets. But it’s more complex than a simple analog-to-digital transition. Young generations face different economic realities that often require geographic and professional mobility, making maintaining extensive collections of physical objects impractical. They’ve also grown up with different aesthetic sensibilities and relationships to consumption, often prioritizing experiences over possessions and sustainability over accumulation.

This generational shift mirrors broader changes in how we value and preserve objects institutionally. Instead of the traditional approach of comprehensive preservation, we need a more nuanced framework for collections care decisions. This framework must balance multiple factors: cultural and historical significance, available resources, potential uses, and preservation viability. However, perhaps most crucially, it must consider context – the web of relationships and meanings that make an object genuinely significant.

Context transforms objects from mere things into carriers of meaning. An object’s significance lies not just in its physical form but in its relationships: to its community of origin, to the stories it can tell, to the communities it serves today, to other objects in the collection, and to contemporary dialogues and issues. This contextual approach helps us make more intelligent decisions about resource allocation, focusing our preservation efforts where they can have the most meaningful impact.

This shift toward context-driven preservation intersects with changing realities in cultural heritage funding. Increasingly, grants and foundations are moving away from traditional collections care funding in favor of community engagement and programming initiatives. This isn’t simply a challenge to overcome – it’s an opportunity to reimagine how we approach collections care. Those charged with preserving cultural heritage must now think creatively about interweaving collection care with community engagement, developing purpose-driven preservation strategies demonstrating how objects can actively serve community needs and interests. Rather than seeing this as a choice between caring for collections and serving communities, we must show how these missions are fundamentally interconnected.

However, this emphasis on context doesn’t mean we should dismiss pure aesthetic value. Some objects possess inherent power through their visual or material presence alone—what we might call “art for art’s sake.” Yet even these seemingly context-free aesthetic objects exist within implicit frameworks: artistic traditions, material cultures, economic systems, and preservation choices. What’s changed is our willingness to acknowledge and examine these frameworks rather than present objects in an artificial vacuum.

As we look to the future of heritage conservation, these challenges become personal and institutional. How do we decide what to preserve when younger generations develop fundamentally different relationships with material culture? How do we balance preserving physical objects with the growing importance of digital heritage? What happens to the stories embedded in objects when the next generation chooses not to keep them?

The future of collections care lies not in treating everything as a Rembrandt but in making thoughtful, context-aware decisions about preservation. This means being more strategic about what we preserve and how. It means considering the entire web of relationships and meanings around objects. It also means being open to new ways of preserving and sharing cultural heritage that might differ significantly from traditional approaches.

Ultimately, the objects we choose to preserve and how we care for them reflect our past, present values, and hopes for the future. As museum professionals, our challenge is to navigate these generational shifts and changing values while maintaining our core mission of preserving and sharing meaningful aspects of our cultural heritage. Perhaps the solution isn’t to lament younger generations’ different relationship with objects but to understand it as part of the evolving story of how humans relate to their material world. Like Wainwright’s celestial metaphor suggests, we’re all moving through our own galaxies of meaning, watching pretty things pass through our orbits, deciding what to hold onto and let go.