The traditional model of living historical education often relies heavily on passive observation – visitors read panels, view artifacts behind glass, or listen to reenactors perform a task. However, a different approach is emerging, transforming these passive experiences into dynamic, hands-on learning opportunities that engage multiple senses and create deeper connections to historical narratives while teaching STEAM concepts through authentic historical practices.

When visitors physically engage with historical processes and crafts, they develop a more intimate understanding of the past while naturally encountering fundamental concepts in science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics. This kinetic learning approach lets participants get dirty with history while discovering the sophisticated knowledge embedded in traditional practices.

Interdisciplinary Learning Through Historical Practices

Quilting: Geometry in Action

Traditional quilting serves as a sophisticated laboratory for geometric concepts. Visitors who work with conventional patterns naturally engage with mathematical principles, including symmetry, tessellation, fraction work, and spatial reasoning. Creating complex geometric patterns through simple shapes helps develop mathematical intuition and precise measurement skills. Historical quilting patterns often demonstrate advanced mathematical concepts like rotational symmetry and geometric transformations, making abstract mathematical ideas tangible and practical.

Seed Saving: Living Biology Lessons

The historical practice of seed saving provides a direct window into biological concepts. While engaging with traditional agricultural practices, participants learn about plant life cycles, genetics, and natural selection. This hands-on experience with seeds connects visitors to historical agricultural methods and fundamental concepts in biology, including plant reproduction, genetic diversity, and adaptation. The process demonstrates how historical farmers developed a sophisticated understanding of plant biology through careful observation and selection.

Carpentry: Applied Physics and Geometry

Traditional woodworking techniques naturally incorporate principles of physics and advanced geometry. Visitors engage with historical carpentry methods and encounter concepts like mechanical advantage, force distribution, and structural integrity. Measuring, cutting, and joining materials provides practical experience with geometric principles including angles, proportion, and spatial relationships. Historical joinery techniques often demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of materials science and engineering principles.

Pottery: Geological Sciences and Chemistry

Working with clay connects visitors to both geological processes and materials science. The pottery experience teaches participants about mineral composition, physical properties of materials, and chemical transformations through firing. Traditional glazing techniques incorporate practical chemistry lessons, while the pottery process demonstrates principles of thermal dynamics and physical changes in materials. This hands-on experience shows how historical artisans developed sophisticated understanding of materials through experimentation and observation.

Baking: Chemistry in the Kitchen

Historical baking practices provide an accessible introduction to chemical reactions and precise measurement. As visitors work with traditional recipes, they encounter concepts like fermentation, protein chemistry, and the effects of temperature on chemical reactions. The process demonstrates how historical bakers developed practical understanding of complex chemical processes through careful observation and experimentation.

Multiple Pathways to Understanding

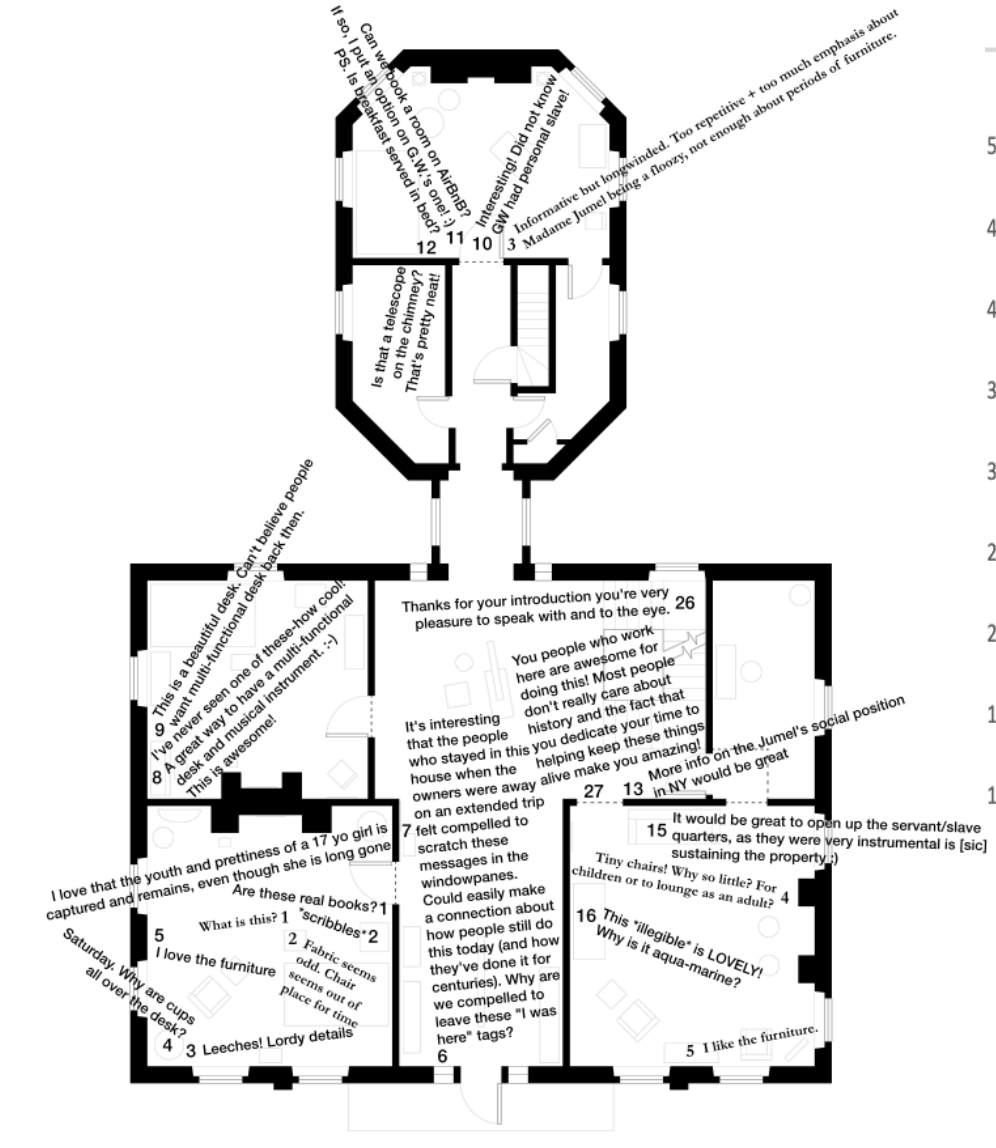

These kinetic learning experiences accommodate diverse learning styles and abilities while naturally integrating STEAM education into historical interpretation. Some visitors might connect deeply with the mathematical precision required in quilting, while others might find their understanding through the tactile experience of working with clay or sorting historical materials. This multi-modal approach ensures that both historical education and STEAM concepts become accessible and meaningful to a broader range of learners.

Creating Lasting Impact

The impact of these interdisciplinary kinetic learning experiences extends beyond the immediate activity. When visitors actively participate in historical processes, they develop:

- Deeper understanding of historical contexts and scientific principles

- Increased appreciation for historical innovation and problem-solving

- Better retention of both historical and STEAM concepts through physical memory

- Enhanced critical thinking skills through hands-on problem solving

- Stronger connections between historical practices and modern science

These experiences help demonstrate that historical practices weren’t simply crude predecessors to modern methods, but sophisticated systems that incorporated deep understanding of scientific and mathematical principles. Visitors begin to appreciate historical figures not just as people of the past, but as innovative problem-solvers who developed complex understanding through careful observation and experimentation.

Looking Forward

As we continue to develop and refine these kinetic learning experiences, we’re seeing how they can transform both historical and STEAM education from passive reception of information into active, engaging processes of discovery. This integrated approach doesn’t just teach history or science – it demonstrates how these fields have always been interconnected through human innovation and problem-solving.

The success of these programs suggests that the future of education lies in breaking down artificial barriers between disciplines and creating opportunities for visitors to discover knowledge through direct experience. By literally putting historical practices in people’s hands, we’re not just teaching about the past – we’re helping visitors develop a deeper understanding of how human knowledge and innovation develop across time.

Through these hands-on experiences, history becomes not just a subject to study but a process to participate in, creating deeper understanding of both historical practices and the fundamental principles of science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics that underlie them.