Old Salem Tavern

Sneaking into my mom’s kitchen pantry, I marveled at the myriad pasta types. Our Italian-American family had so many varieties. Slyly, I’d lift several boxes, and once back in my bedroom/art studio, I would spread out my loot. Back then, my bedroom was my sanctuary, a place to draw and make building models. Compared to my older brothers, both into sports, girls, and not much else – I must have looked alien to my family – holed up in my sanctuary, quietly drawing and making models of buildings.

Each year for Halloween, I would spend months creating a large “haunted house” model replete with miniature fireplaces and cardboard chimneys, through which, I would stream up smoke. Since my secret sauce, so to speak, to create the smoke effect, was a lit cigarette of my dad’s, it’s a wonder the whole thing didn’t engulf in flames at some point.

Not being one to make friends easily, if at all – this was further compounded by our family abruptly moving to Charlotte, North Carolina from Pittsburgh in 1976. So, in the latter part of that decade, I kept more and more to my model-building self in my bedroom/studio sanctuary. I was a new student at the Albemarle Road Junior High School, and my Social Studies teacher, Mr. John Pappas, perhaps sensing my isolation, pulled me aside and asked me whether I wanted to join the Tar Heel Junior Historians’ Association (THJH). Though I was unsure what that was exactly, Mr. Pappas informed me it would involve a trip to Raleigh – so I said yes.

The annual THJH gathering featured a competition between participants to research and build models from a long list of historic sites throughout North Carolina. Having several year’s worth of experience with my imaginary haunted structures, it felt fun to create models of actual local Mecklenburg County sites. My first time in the competition, I constructed a model of the Hezekiah Alexander House. The following year, it was the Hickory Grove general store on Old Concord Road.

In my third and final year of participation, I designed a model of a small Queen Anne Victorian house which as I recall, I saw mentioned in local paper. In a photo, the house was on blocks, slated to for possible removal. This became my first in-depth research project. Not only did I track down the new owner of the house, but I managed to obtain blueprints, from which I constructed my model. Luckily, this treasure was saved and ultimately placed on the corner of Poplar and Seventh Streets within Charlotte’s Fourth Ward.

Clearly, stealing my mom’s noodles was justified. This Queen Anne house had a wood structure with an exterior clapboard Surface. Reproducing the appearance of clapboard proved quite a challenge, until I had a Eureka moment – Linguini! Of course – it had the exactly the correct scale and appearance. In short order, I had torn open the linguini box and slapped on some pieces of ‘clapboard’. It looked perfect! Fast forward several months later, and I was elated to accept the title of statewide THJH champion. Serendipitously, someone suggested I become “an architect” – which was, I assumed, a great suggestion, even though, up until that moment, I had not ever heard of that term. Yet this encouraging bit of praise led me on a new path and altered my trajectory in life.

One of the many benefits of the Tar Heel Junior Historians’ experience was traveling to visit various historic sites and monuments throughout the state. From this experience, I soon learned that the larger, more honorific sites offered little appeal. It was smaller houses and domestic spaces that I loved. Perhaps because I stayed in my room all day alone, my natural interests concentrated on others who did the same. Historic sites to me were not about the big things. Instead, they were the little moments – sitting on a chair looking out a window. The mundanity of small domestic spaces and the ways people lived in them spoke to me far more than the majestic, and this is a feeling I’ve carried with me up until the present.

Clear examples of this type domesticity I’m referring to were ones I discovered in one of the stop-offs on our Tar Heel Historian tour – the strikingly beautiful colonial town of “Old Salem” in Winston-Salem, NC.

The Town of Salem was founded by Moravians in 1766, in what was then called the “Wachovia Tract” in the middle of the North Carolina Piedmont foothills. Salem was to serve as the urban center for all the other Moravian communities in this same tract of land. It was one of the earliest planned communities of the New World, organized around the north-south axis of Main Street. Though the town was not largely agricultural in any sense, each house was built on a tract of land just large enough to allow for household use, i.e. a small vegetable garden. The town was in fact primarily a mercantile business economy, and soon became known for its beautiful buildings, well-tended gardens, and orderly landscape, a century later, its ornamental flower borders. Salem has been continuously inhabited since the founding, and amazingly, still exists in its originally designed state.

The Moravians (Unitas Fratum) were a group of early Protestant religious immegrants originating from the Bohemian lands of Europe. They originally organized in 1457, and by 1517 the sect numbered around 200,000, with over 400 Parishes. In 1735 the first Moravian refugees came to the American Colonies, attempting to establish a settlement in Georgia. After this unsuccessful attempt, they went on to establish several lasting sites in Pennsylvania (the towns of Bethlehem and Nazareth). After establishing these Northern colonial towns, some Moravians moved south into the Carolinas, creating the planned agricultural communities of Bethabara, Bethania, Friedberg, Friedland, and Hope. Eventually, they established the town of Salem (1766) to act as the mercantile, religious, and urban center for these outlying villages. The guiding spiritual principle was reflected in the Moravian motto: In Essentials, Unity, In Non-Essentials, Liberty, and in All Things, Love.

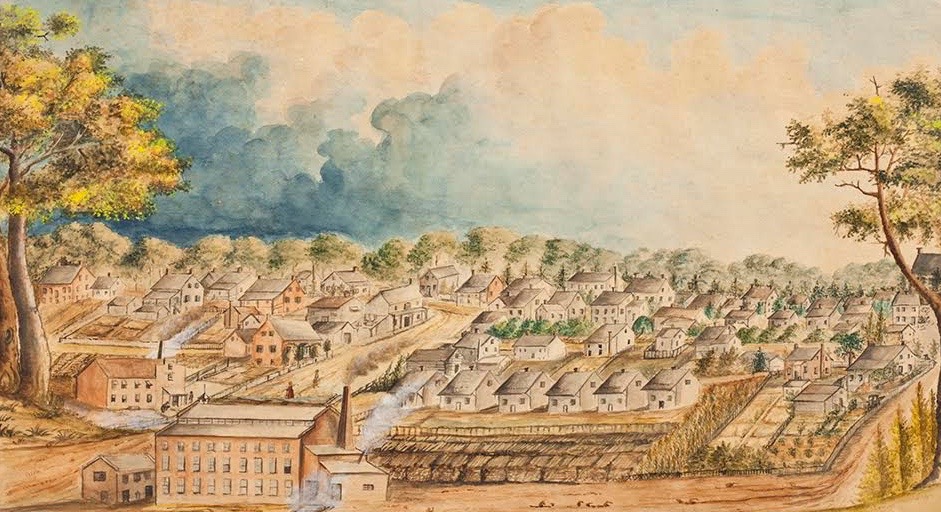

Even in the oldest images of Salem, you can still recognize today’s town. You can clearly see Main Street, the Home Moravian Church, and all the dwellings lined up in orderly succession. As a child, I didn’t truly “see” any of this urban morphology. What I remember from my THJH visits to Old Salem are the great sugar cookies and beautiful fall leaves on the big street trees. I didn’t quite get the Moravians and how they fit into the whole revolutionary war, or any understanding of “difficult narratives”, but for a 12-year-old, that was OK; the trip was fun anyway.

Even in the oldest images of Salem, you can still recognize today’s town. You can clearly see Main Street, the Home Moravian Church, and all the dwellings lined up in orderly succession. As a child, I didn’t truly “see” any of this urban morphology. What I remember from my THJH visits to Old Salem are the great sugar cookies and beautiful fall leaves on the big street trees. I didn’t quite get the Moravians and how they fit into the whole revolutionary war, or any understanding of “difficult narratives”, but for a 12-year-old, that was OK; the trip was fun anyway.

The present historic site of Old Salem, is much as it always has been, a seamless mix of real residential homes with historic house museums and quasi-commercial and commercial establishments. It has never lost its sense of habitation. In fact, almost the entire town is original, with very few reconstructed buildings. When you visit this site, what you see is what was there. That in itself is pretty remarkable. Salem’s original Main Street flows directly into the modern city center of Winston-Salem and remains Main Street. In fact, the modern city of Winston-Salem owes its urban form to the city planning of its Moravian founders. There is no strict demarcation between “history” and today.

Although buildings were removed throughout the restoration process, of the 109 buildings in Salem, 77 are original (thus, 70% original). This is in contrast to Williamsburg’s 300 buildings, where only 88 are original (29%). In this way, Old Salem holds a more unique place in the family of these types of historic sites in that it is not a created historic village or a predominantly reconstructed town. It’s the real deal – messy, fuzzy, and confusing – a perfect metaphor for life.

The contemporary historic site of Old Salem Museums & Gardens (OSMG) consists of an entire landmarked district containing the world-class Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), what seems like an endless Thomas A. Gray rare book library and document archive, the extensive Venturi/Scott Brown-designed Visitor Center, the St. Philips Heritage Center for African American history, Salem Academy & College, and the original active Home Moravian Church congregation. On the several days that I was on site that week, there were multiple school field trips, whose combined attendance total exceeded 2000! Busy and active do not fully describe this bustling historic district!

So here I find myself again, some 35 years after my initial THJH visit – this time, getting the chance to sleep over in the town’s one and only historic 1784 Tavern! I am initially reminded of my 14-year old self – a young, sometimes confused, and isolated kid. Back then, I had few friends, and I thought I was only person like me. It is not an exaggeration to state that the Tar Heel Junior Historians and by extension, the village of Old Salem, became lifelines for to me, my self-esteem, and my self-value. Suddenly, I realized I could take pride in my talent and aptitude for history and craft-making. These THJH trips nourished my soul when I needed it most, and showed me a world far bigger than my lonely bedroom.

So here I find myself again, some 35 years after my initial THJH visit – this time, getting the chance to sleep over in the town’s one and only historic 1784 Tavern! I am initially reminded of my 14-year old self – a young, sometimes confused, and isolated kid. Back then, I had few friends, and I thought I was only person like me. It is not an exaggeration to state that the Tar Heel Junior Historians and by extension, the village of Old Salem, became lifelines for to me, my self-esteem, and my self-value. Suddenly, I realized I could take pride in my talent and aptitude for history and craft-making. These THJH trips nourished my soul when I needed it most, and showed me a world far bigger than my lonely bedroom.

Recently, Mr. Pappas reached out to me via email, so I want to share with him via this article, just how much his support for me at that time influenced my life and future endeavors.

After undergraduate college, I left North Carolina as soon as I could, thinking that the political culture of the state was not supportive enough for me. I went on to live my life full of loving and caring partners and family members who nurtured me and taught me many things that I never even knew I should have known. I am the product of those whose lives have touched mine. For the past few decades, I’ve watched North Carolina from a distance morph from a red state (conservative) into a more purple state, eventually taking on the title of an official swing state -heading toward blue (progressive).

Last year with Deb Ryan I co-authored The Anarchist Guide to Historic House Museums. The book is now in its 3rd printing in a single year, and briefly held a place as Amazon’s #1 museum-related bestsellers in February 2016. In the book, I had made it clear that I was a museum anarchist, someone who did not think about history like other people. To me, historic sites are valuable not only in telling us about the past, but more importantly to inform our lives today in the present. When it comes to seeing and interpreting historic sites, I see myself not as staid or static, but more of a free-radical My cultural consulting firm Twisted Preservation prides itself on taking on special boutique projects which purposely blur or redraw the original boundaries between preservation and interpretation.

For these reasons, I was initially stunned that the board of Old Salem, through a search firm of their own, contacted me for an interview for their available President/CEO position. Though I stated that I would be far too radical for them, and not the best leader for a site in the middle of “conservative” North Carolina, they kept pushing back, and insisting I hear them out and come down for an interview.

As the possibility of my hire became imminent, I offered a big test to them – a suggestion that during my orientation week, I be allowed to conduct one of my so-called one-night stands in a building of theirs and blog about it. Surely that would scare them to death, I thought. Well, I was wrong. Not only did they agree to it, they supported the idea with a sincere interest and almost childlike gusto. The entire experience was engaging and thought-provoking, both on personal and professional level.

Years prior, a friend once encouraged me to “run into the roar” and for me, honestly this experience was running into the proverbial roar. Not in an inherently bad or scary way, rather in a way that made me face my childhood fears and preconceptions of what North Carolina was like (Jesse Helms and all). So, I write this blog in an honest state of self-reflection, and I am addressing what are for me, the most common, yet multi-layered, preservation-y and museum-y terms and tropes: history, authenticity, interpretation and yes, even costumes.

Just prior to my orientation visit, the staff mailed me a thickly bound set of documents providing me with a nice overview of the history of the Tavern, as well as the beliefs and achievements of the Moravian Church Community. The Moravians were no status quo group, rather they were 15-century religious reformationists long before Martin Luther’s official Protestant Reformation of 1517 began. They believed in educating women and early on, established a Salem Girl’s primary school, then an academy (high school) and ultimately the what is now the oldest continuously-operating college for women, founded in 1772. They believed in the spiritual equality of all members of the church, regardless of status, even if they were slaves. Members such as the once enslaved then freed potter Peter Oliver were buried side by side, regardless of socio-economic status. Giving further credence to this notion is the simplicity with which each grave marker is laid flat, each uniformly sized and spaced, in their Moravian church graveyard known as God’s Acre.

Delving into their thick compendium of papers, I expected a standard mind-numbing list of names and dates, but these Moravians turned out to be not what I expected, and in fact were pretty cool. Right on page one, this jumped out at me:

“Whereas it is the duty of the Board of Directors of the Congregation to supervise, with a watchful eye, the tavern, and it is their ardent desire that the guests who come here (who are of very different dispositions and customs, yea, even occasionally enemies and spies) may be served by our Brothers and Sisters thus, by their correct conduct, without words, testify to Jesus’ death, and in their difficult office and calling, be an honor to the Lord and Congregation.”

Coming out of the recent U.S. Presidential election, this sentence screamed out to me:” who are of very different dispositions and customs, yea, even occasionally enemies and spies”. Immediately, my perception was realigned. In the middle of the wilderness of late 1700s North America, these reformationist Moravians had established what was easily one of the most progressive towns in all the colonies. Having recently seen the 2016 Presidential election results map of North Carolina, I came to understand that one of the most systemically progressive, liberal areas (shown in purple/blue) in North Carolina is Forsyth County, and its county seat, Winston-Salem. It seemed logical that the forward-thinking Moravians sowed the seeds for this several hundred years prior.

Coming out of the recent U.S. Presidential election, this sentence screamed out to me:” who are of very different dispositions and customs, yea, even occasionally enemies and spies”. Immediately, my perception was realigned. In the middle of the wilderness of late 1700s North America, these reformationist Moravians had established what was easily one of the most progressive towns in all the colonies. Having recently seen the 2016 Presidential election results map of North Carolina, I came to understand that one of the most systemically progressive, liberal areas (shown in purple/blue) in North Carolina is Forsyth County, and its county seat, Winston-Salem. It seemed logical that the forward-thinking Moravians sowed the seeds for this several hundred years prior.

My first day visiting Old Salem as President-Elect, began early. I woke up, got dressed, and opened the door onto Main Street in Old Salem. There was a vibrancy in the air and symphony of sounds echoing down the street. There were cars, horse-drawn carriages, joggers, people unloading groceries into their houses, and about 800 school children on field trips. Fun Fact: As I was walking, I stumbled upon a small ground plaque on one of the sites. The first Krispy Kreme Doughnut Shop was built right on Salem’s Main Street!

The first order of business was to stop by the Single Brothers House, c. 1769. This would be the location of many a staff meeting as well as my future office location. It’s a strongly designed building of timber frame with brick infill. That particular morning, some of the interpretive staff had gathered there, so that I could be briefed about the Tavern and discuss questions regarding my one-night stand. I expected a long table of serious historian interpreters, dressed up in somewhat creepy costumes, telling me all about the importance of their “period of interpretation.” Instead, I was greeted by a welcoming group of dedicated history nerds like myself. Lively conversation ensued and two hours sailed by. Any question I asked was freely and fully answered. Never once did I feel, as I often do in historic sites, that there is an effort to diminish or not interpret the history of one or more marginalized groups. My questions ranged from issues regarding slavery at the site, the use of chamber pots, and why do they wear those funny wrap-around head bonnets?

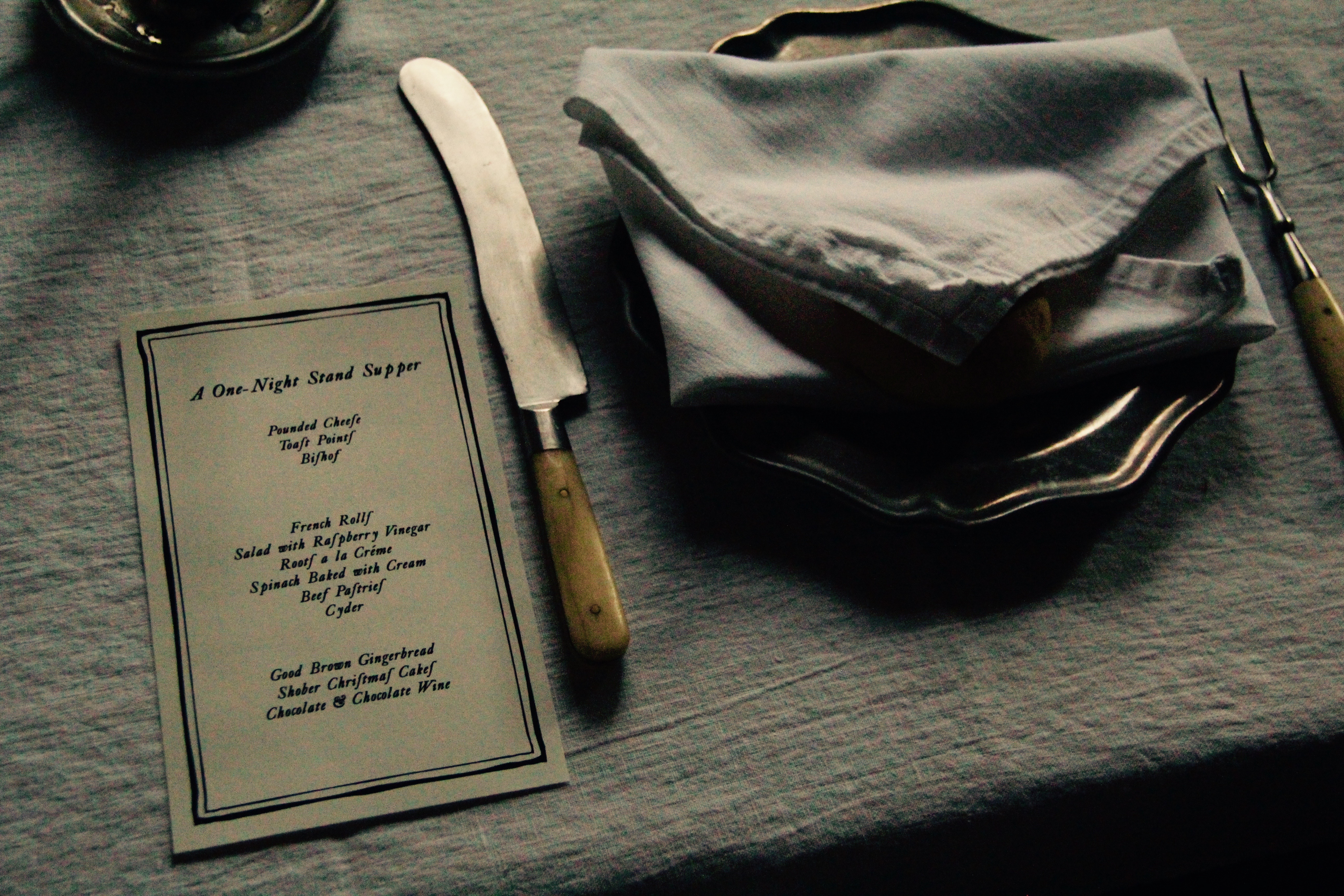

The kindness and generosity of the staff at Old Salem was overwhelming. Similar to some of my other one-night stand events, it would be preceded by a group dinner, however this dinner would serve the additional purpose of welcoming me into the Old Salem community. As part of Old Salem’s extensive food and horticulture program, this meal would be made entirely from food grown on site, hand-picked by myself and several others later that afternoon. What’s more, it would be prepared downstairs in the original Tavern kitchen. But that wasn’t all. Our evening would start with a carriage ride around town, while musicians serenaded us in front of Salem Square, just as the Moravians had done for old George Washington himself. A final added touch was the night watchman replete in interpretive costume, making the traditional Moravian evening rounds, in which he would sound the “all’s clear” signal by blowing into a conch shell.

Although not designated at Old Salem as such, a colleague of mine, who specializes in African-American heritage, once explained to me that often night watchmen who sounded the all’s clear, were more specifically informing the residents that all the slaves were back in their quarters. So, for this reason, the topic of slavery stuck in my mind. During my staff meeting, deeply probing discussions concerning slavery ensued, particularly how this institution of human bondage was negotiated within the Moravian Communities. It seems difficult to reconcile how could a group so progressive and so dedicated to spiritual equality would justify human slave ownership. Needing help understanding this, I continued to ask questions. The scholars & interpreters responded thoughtfully. There was a general consensus that it was difficult to imagine the social and spiritual machinations that could have taken place to justify slavery in this otherwise progressive community, that or perhaps an emotional disconnect, that prevented them from even contemplating such a notion.

(see Moravian Church formal apology: http://africanamericangenealogy.blogspot.com/2006/04/moravians-issue-apology-for-churchs.html )

Sitting to my right was Cheryl Harry, Director of African-American Programs at Old Salem. She provided me with some historical background, as did some of the other specialists in Moravian history. The truth is that slavery has a complicated history in Old Salem. Refreshingly, Old Salem as a historic site was one of the very first in the U.S. to actively investigate, interpret, and restore artifacts and buildings reflecting the African-American experience. Their archeological and restoration work predates many other heritage sites in recognizing the lost narrative of the black populations.

The first enslaved person purchased by the Moravian Church (Wachovia Administration) was in 1769, and his name was Sam. He was later baptized into the Moravian Church in 1771 and re-named Johannes Samuel. In Salem, except in special circumstances, individuals were subject to Slave Regulations. These regulations prevented the ownership of slaves by individuals of the community. In fact, much like co-ops today, the church collectively owned all the land, residents could only own the structures and landscape improvements. So while an individual could not own a slave, the church was able to collectively own slaves. When the construction of Salem began in 1766, there was more work than the Moravian population at the time could do and this resulted in hiring from outside of the community. Certain jobs were performed by outside white hired labor and by enslaved persons rented from outside owners. It seems clear to me that much of the work in Salem was accomplished by combinations of freemen, slaves, and strangers, a term for white non-church members. There was no way that Moravian Church members alone could handle the operations of the entire town.

This resulted in the “borrowing” of slaves, or hiring from outside of the community. During the construction of Salem, certain jobs were performed by outside white hired labor and enslaved persons rented from outside owners. It seems clear to me that much of the work in Salem was accomplished by combinations of freemen, slaves, and “stranger” white non-church members. It is my belief that there was no way that only Moravian Church members could run the entire town.

At first, the enslaved black people owned by the Wachovia Administration were supposedly treated as spiritual equals. They worshiped alongside the white members and were buried in the same graveyard, interspersed with white burials. There are historic records of church leadership requesting that slaves not be clothed in anything better than other members of the congregation – one wonders if they could be clothed in anything worse. There is some suggestion that the Moravians had a difficult time distinguishing between the moral and social constructs of slave ownership. I wonder if there are any first-hand accounts of how the slaves felt about all of this. This of course, would not justify slavery on any level – it could simply present a more nuanced understanding.

My hosts explained that in the first half of the 19th century, ownership of slaves in Salem by individuals was increasing, often in violation of the regulations. Others felt that the presence of slaves could be harmful to the Moravian youth, allowing their community’s work ethic, or which there was great pride, to be supplanted by laziness. Ultimately it did become permissible, although frowned upon, for some individuals to own slaves if they were kept outside of the town proper. Other owners were admonished or required to remove their slaves.

Many of the enslaved people within the Moravian communities of Wachovia learned specialty trades, and their skills became very valuable. Records and objects at Old Salem’s Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) reveal that Southern enslaved artisans produced some of the finest furniture, pottery and domestic arts. Enslaved hands produced many everyday items. I often think about how the silent, marginalized people at a historic site played such an important function. Just like the furniture itself, without the hidden “constructions” of the work of these people, much of what has been restored and open to the public as “heritage” (the pretty stuff) wouldn’t have been created in the first place. In many ways, we must go into the MESDA and flip the chair over, look for fingerprints in the bricks & pottery, or pull out a drawer and look inside the furniture casing to find the hidden legacy of the enslaved.

Eventually, the acceptance of slave ownership took hold in Salem, and by 1816, a separate slave burial ground was created, and in 1822, a black Moravian church congregation was formed, followed by the construction of a log cabin church building in 1823, now known as the St. Philips Moravian Church. Slave Regulations in Salem ended in 1847, and individuals were then able to own enslaved people within town boundaries.

Very early and cursory research has suggested that slave ownership in Salem involved approximately 16% of the town’s free population (1860: 160 enslaved people, 40 slave houses). Though a real and thorough study needs to take place, it appears as if there were 47 enslaved people owned in Salem in the 1840s, down from 83 in the 1830s. The slave population was most likely tied to the Moravian-owned textile mills that were built just north of the town center. While these compelling statistics are being verified, Old Salem has tentatively proposed a long-term archaeological project that incorporates the lot location of owners and the notation of slave houses held by those owners. Because much of the town is original, the potential for archeological information relative to the urban slavery narrative is quite high. This could become one of the most valuable sites for gathering information about slavery in North Carolina.

Very early and cursory research has suggested that slave ownership in Salem involved approximately 16% of the town’s free population (1860: 160 enslaved people, 40 slave houses). Though a real and thorough study needs to take place, it appears as if there were 47 enslaved people owned in Salem in the 1840s, down from 83 in the 1830s. The slave population was most likely tied to the Moravian-owned textile mills that were built just north of the town center. While these compelling statistics are being verified, Old Salem has tentatively proposed a long-term archaeological project that incorporates the lot location of owners and the notation of slave houses held by those owners. Because much of the town is original, the potential for archeological information relative to the urban slavery narrative is quite high. This could become one of the most valuable sites for gathering information about slavery in North Carolina.

Following the Civil War, former slaves eventually moved outside of the town center into an area now known as Happy Hill. This residential area still exists and remains occupied. I asked my hosts to show me Happy Hill and explain the connections between the African-American district of Old Salem, Happy Hill, and the Moravian town center. As we walked around the land surrounding St. Philips Church, my host Cheryl pointed off into the distance and noted, “That is Happy Hill over there. There is a path still in existence that ran directly from center city Salem over a creek, and into the heart of Happy Hill”. I asked if she would take us there and she agreed.

The main road, named “Liberia Street,” leads directly down to a footbridge that crosses a creek and leads to the town center of Salem. My host walked me across the footbridge and into Happy Hill. We walked up the main road and stood at the top of the hill. As you stand there, you are struck by how close it is to Salem; in fact, you can see Salem College and other Moravian Church buildings. Looking north and past Old Salem, modern skyscrapers of downtown Winston-Salem looms off in the distance to the east. There’s a clear divide between Happy Hill and the adjacent Old Salem, and it seems so close you could almost throw a rock into Salem Square.

The main road, named “Liberia Street,” leads directly down to a footbridge that crosses a creek and leads to the town center of Salem. My host walked me across the footbridge and into Happy Hill. We walked up the main road and stood at the top of the hill. As you stand there, you are struck by how close it is to Salem; in fact, you can see Salem College and other Moravian Church buildings. Looking north and past Old Salem, modern skyscrapers of downtown Winston-Salem looms off in the distance to the east. There’s a clear divide between Happy Hill and the adjacent Old Salem, and it seems so close you could almost throw a rock into Salem Square.

Before urban renewal devastated its built fabrics, the small community of Happy Hill contained the first school for black children in Winston-Salem and Forsyth County, along with rows of small shotgun houses. Today there are only a few original dwellings left. Cheryl walked me around two that she hopes will be restored and used to tell the history of the freed slaves and, later, the African-Americans who called Happy Hill their home through the Jim Crow era. As I walked around, I couldn’t help but wonder why Happy Hill was subjected to urban renewal, while Old Salem was restored. Was this urban renewal meant to address the poverty brought on by slavery, itself just a variant form of the preexisting segregation and racism?

It may seem unexpected to be discussing the Jim Crow Era at a one-night stand” that is taking place in a 1784 Tavern, but it made perfect sense to me. The legacy of the Moravians and Salem is not merely contained neatly within the beautifully restored town center, or in the archeological artifacts. The legacy can be found in all the families and individuals that are descendants of slaves from Salem. There is a present-day local black population that traces ancestry to the enslaved and free black population of Wachovia, who understand very well who their antecedents are and where they are from. There is also a substantial population of black people in Winston-Salem and Forsyth County who derive their ancestry from broader parts of the South and whose families were part of the post-Civil War northward migrations from farms and plantations to more industrial city centers. Old Salem is a site for them as well. It can and needs to speak to all of us.

With all this new information, I was looking forward to my one-night stand dinner at the tavern. We had invited a lively group of people who helped put all of this into some context, and helped me expand my understanding of Old Salem. I have never understood why the restoration of one narrative needs to be at the expense of another. We can do better than that.

Following my meetings and visit to Happy Hill, I was off to the Old Salem gardens, where I assisted in gathering up the veggies for evening’s one-night stand meal. My hosts handed a basket and gave me a list of items they needed. We walked around the site, visiting various period gardens, and collecting kale, carrots, onions, lettuce, thyme, and parsley among other things. We ran into Chet Tomlinson, of the trades staff, and an expert gardener who supervises one of the house garden programs. He showed me around and we collected some more food from the landscape. In the past, I’ve had some unease with the seriousness I’ve encountered among costumed interpreters. This experience however was not at all like that – it was fun and seemed perfectly natural. He wasn’t trying to be someone else, or a famous person. He was simply a gardener.

http://www.journalnow.com/gallery/news/frank-vagnone-s-one-night-stand-in-the-tavern-museum/collection_59e0aa20-b846-11e6-a1dc-bb57d2097e16.html

Following my trek across the town of Salem, I returned to the downstairs Tavern kitchen. My new friends, Darlee Snyder – Director of Education & Outreach Programming & Joanna Roberts – Assistant Director of Interpretation, had started a fire in the hearth and were unpacking for the evening’s one-night stand dinner. They welcomed me with an apron and a glass of cider. As living history interpreters, they understood the power of tactile involvement with the action of what was taking place. They didn’t skip a beat, but handed me a bucket and one interpreter told me to follow her outside to the well. We pumped the water and joked and laughed as we made our way back to the kitchen. “Can you clean the veggies?” she asked. So I proceeded to wash the soil off my gathered loot from earlier in the day as we worked and chatted and gossiped a bit by the hearth.

Their head coverings, I teased, made them look so stern – and yet they were both so nice and fun it was hard to reconcile the two in my mind. They smiled, paused, and told me that someday they would share with me the whole larger discussion they had had about the head garments. This discussion of headdresses made me wonder why Muslims’ wish to wear respectful headdress was so controversial to some, while these headdresses are seen as typically wholesome “Americana”. Curious about how they were worn, they allowed me try one on for size.

Just as soon as I had finished cleaning the veggies, I was called upstairs by Earl Williams of the Education Staff – We had to tighten the ropes to my bed and then make the bed.

Just as soon as I had finished cleaning the veggies, I was called upstairs by Earl Williams of the Education Staff – We had to tighten the ropes to my bed and then make the bed.

Starting to get hot and sweaty with all this rope tightening and bed making, I went over to the window to open it. Guess what? No go! Painted shut. This would never do, I thought, shaking my head. But for now, I let it go, and lay down on the bed. My hosts brought in a reproduction of a bed rug for me to use. We threw it over the newly prepared bed and I plopped down on top of it. It looked a lot like a 1970’s green shag rug, but it really felt luxurious. It was quite heavy and I thought that it would be too suffocating to use. In reality, it was extremely comfortable. It was not heavy at all and provided just the right amount of snugness. Another great example of how actual use changes perceptions. After a bit of rest, I got word the sisters requested my presence downstairs to help prepare dinner, so I got up and rushed downstairs.

The sun was setting, and the kitchen became darker. The flickering orange glow of the fire covered everything with a moving projection of shadows. Rolling up my sleeves, I first threw in a few more pieces of wood in the fire and then commenced with dinner prep. When this was done, I moved from the kitchen, up the uneven stone steps, and to the front public dining room, where we set up for our dinner. Everything looked beautiful and ready for our guests to arrive.

My guests for the dinner included stakeholders from all over Winston-Salem. My request had been that our dinner table represent the community that surrounds the historic site. We had elected officials, an artist/maker, a gentleman who gave the keynote speech for Old Salem’s 2015 Naturalization Ceremony, the Director of the Old Salem African-American Programs, and various board and staff members. As we gathered on the porch of the Tavern, a group of musicians, led by Scott Carpenter, began to play welcoming music.

My guests for the dinner included stakeholders from all over Winston-Salem. My request had been that our dinner table represent the community that surrounds the historic site. We had elected officials, an artist/maker, a gentleman who gave the keynote speech for Old Salem’s 2015 Naturalization Ceremony, the Director of the Old Salem African-American Programs, and various board and staff members. As we gathered on the porch of the Tavern, a group of musicians, led by Scott Carpenter, began to play welcoming music.

From the moment we sat down, we couldn’t stop talking. It felt like this was exactly how this Tavern was used. It housed political, and social discussions with people from all walks of life. It existed as a conduit between the spiritual community of Moravians and the strangers, a term meaning essentially anyone from the outside world.

After dinner, the guests all descended into the downstairs kitchen, where the fire continued at brisk pace. The sisters had prepared a special mixture of wine and think European hot chocolate. Since I rarely imbibe, I stuck to the hot chocolate. It was such an enjoyable ending to the day’s events. We made a toast to our hosts, and quickly followed it with another, more symbolic toast to all the Salem hosts, both past and present, free and enslaved, for their work in creating this amazing town of Salem, and showcasing the town’s warmth and hospitality.

After the toast, we discussed the relationship of slavery, inclusion, and diversity to the operations of the Tavern itself. Just like the larger Moravian slave narrative is complex, so too is the Tavern’s relationship to slavery. The Tavern stewards employed several slaves throughout the years. A few were bilingual and spoke German and English. A point was made that just above the room we were standing in was a room that quite possibly was the dwelling place of slaves. A narrow stair, with no other exits, accesses it. Interested, a few of us went up into the dark space and contemplated that possibility.

One by one, our guests left the warm kitchen, heading out the side door with hugs and selfies. Eventually the only two left in the entire tavern were me and my partner, Johnny Yeagley. We sat by the fire, occasionally putting another log or two, while we heated water for our tea. There was strangely satisfying immediacy to watching the wood flame up and heat the cast iron pot, which in turn held our water. The steam told us that the water was boiling and ready for the ladle. We kept filling up our mugs with hot water while chatting about the day’s experiences.

Holding my glazed mug, I contemplated how these objects of material culture became alive only when their form was tied to their use. Sure, this mug could be displayed in a decorative-arts museum with a text box beside telling me who made it and when, but it seemed far more powerful for me to be holding it, filled with boiling water and tea, sitting by the fire chatting. When critiques of heritage sites say that they are “boring” I often wonder: what exactly does that mean? Surely the mug is not boring (or exciting for that matter). It simply exists as an object for use. In that use, I can feel all the sensory things that we humans feel while holding it, but in themselves, I feel these objects hold very little substance without this use.

Johnny said goodnight and headed back to our guest accommodations, walking down Main Street into the darkness. After lighting a lantern, I made my way upstairs to my bedroom, stopping in each room to snoop around and imagine thes filled with travelers and other strangers.

The views out into the town landscape through the wavy glass window panes looked like contemporary art paintings. I noticed a man walking around the street, carrying a conch shell, so I knew he was the night watchman and was going to sound the “all’s clear” message. I went back out to sit on the front stoop, and waited for his call.

The views out into the town landscape through the wavy glass window panes looked like contemporary art paintings. I noticed a man walking around the street, carrying a conch shell, so I knew he was the night watchman and was going to sound the “all’s clear” message. I went back out to sit on the front stoop, and waited for his call.

As I waited, I noticed several people walking their dogs along Main Street. The prevalence of pets in Old Salem was something I had noticed earlier. Many pet owners proudly walk their dogs and gather on street corners to chat. There was also the occasional cat scurrying in and out of a crawlspace, no doubt keeping the rodent population in check! Yet another example of how, even today, Old Salem speaks to the historic habitation in present ways. From very early accounts of the town, pets were considered a part of the community. Several images from the Old Salem and Wachovia Historical Society Collection show dog houses and full integration of four-legged partners. When I inquired about their pet policy, the response I got was: “Beagles, cockatoos, goats, and all other pets are welcome to walk on the streets and sidewalks at Old Salem Museums & Gardens—provided they are leashed.” Now that’s a policy I can live with.

Sitting on the rope bed with my computer, I wrote and uploaded photographs to my social media accounts. It was a bit of a challenge trying to encapsulate the day’s events, especially since so much of what I encountered had upended my preconceptions and expectations. My naïve childhood understanding of Old Salem was forever altered. Forcing a realignment of preconceptions is, in fact, exactly what a historic site can and should do. It can renegotiate what you thought you already knew, and establish a paradigm that you didn’t even know existed. Such is the power of a site like Old Salem.

Sitting on the rope bed with my computer, I wrote and uploaded photographs to my social media accounts. It was a bit of a challenge trying to encapsulate the day’s events, especially since so much of what I encountered had upended my preconceptions and expectations. My naïve childhood understanding of Old Salem was forever altered. Forcing a realignment of preconceptions is, in fact, exactly what a historic site can and should do. It can renegotiate what you thought you already knew, and establish a paradigm that you didn’t even know existed. Such is the power of a site like Old Salem.

Old Salem is now for me no longer a site just about good cookies and beautiful fall leaves. It has taken on the full breadth of maturity and adult contemplation that the world around us has been and still is confusing and full of contradictions. How such progressive, thoughtful white Moravians could perceive people of all races as spiritual equals, yet simultaneously hold ownership and commoditize others is stunning — and that is just one example of the inherent confusions of difficult histories. Yet Old Salem, unlike so many other historic sites, is unafraid of honestly presenting and thoughtfully discussing and interpreting these types of messy historical contradictions, and we, as history lovers, are the better for it.

I did not come back to North Carolina just to hold a one-night stand. Nor, did I come back to North Carolina simply to help run a historic site. I came back to North Carolina for every lonely, scared, marginalized little kid looking around their world and searching for a lifeline in the past to help them in their present. I know I can help shed light on these types of powerful, complicated messages in ways that can help others dream bigger ideas and achieve beyond their own imagination. My job, as I see it, is to find a way into the hearts and minds of all those Tar Heel Junior Historian kids – to make them see that Old Salem is simply a different reflection of an everyday, normal existence. Dogs, trash, cookies, veggies, cars, social vs moral contradictions, and yes – costumed interpreters. This site can represent the extraordinary life of the mundane. But without a doubt, it includes each and every one of us.

The following morning, I locked the Tavern door, and walked up Main Street. People were already walking their pets, the street cleaners were picking up trash and brushing away the fall leaves. Commuters were heading out to work in their cars from their evening street side parking spots. This morning jaunt of mine following my one-night stand, was not a walk of shame. On the contrary, my evening had been sublime, far exceeding my expectations. As bright morning sunshine beamed down on me, I realized that Senator Jesse Helms was no longer to be found, not on the street, at least of all, in the bed that I had been sleeping in last night. In large part, thanks to the transformative power of history (and the shape of linguini), I am no longer that scared, little kid.

Come down to Winston-Salem, North Carolina and visit Johnny, me, and our dog Yogi. Soon the museum anarchist will soon be in the house! In a case of life imitating art, we will be living in an actual historic property called The Fourth House (c. 1767), which is, in fact, the oldest house in Winston-Salem… and keep an eye on what develops at Old Salem Museums & Gardens – they’ve hired me, the Museum Anarchist, as President & CEO. And by hiring me, they have made it 100% clear, they mean business.

Come down to Winston-Salem, North Carolina and visit Johnny, me, and our dog Yogi. Soon the museum anarchist will soon be in the house! In a case of life imitating art, we will be living in an actual historic property called The Fourth House (c. 1767), which is, in fact, the oldest house in Winston-Salem… and keep an eye on what develops at Old Salem Museums & Gardens – they’ve hired me, the Museum Anarchist, as President & CEO. And by hiring me, they have made it 100% clear, they mean business.

THANK YOU:

Ragan Folan

Johanna Brown

Steve Bumgarner

Scott Carpenter

Brian Coe

Tyler Cox

Cheryl Harry

Martha Hartley

Robbie King

Paula Locklair

Joanna Roberts

Darlee Snyder

Lindsay Sutton

Chet Tomlinson

Earl Williams

Robert Leath

Cheryl Harry

Michelle Moon – Twisted Preservation

Elon Cook – Twisted Preservation

John Yeagley – Twisted Preservation

Jon Prown – Chipstone Foundation

Steve Allred – Heritage Carriages

Salem Lower Brass Band

Ken Bennett, photographer

Allison Lee Isley, Winston-Salem Journal photographer: http://www.journalnow.com/gallery/news/frank-vagnone-s-one-night-stand-in-the-tavern-museum/collection_59e0aa20-b846-11e6-a1dc-bb57d2097e16.html

Rebecca McNeely, photographer

North Carolina Museum of History & The Tar Heel Junior Historians

I, too, was inspired to a career in history after tours of Old Salem as a child. Sounds like the beloved living history museum will be in good hands! I’m looking forward to my next visit already

LikeLike

Extraordinary! How thrilling (as a resident of Old Salem) to recognize again that we walk not only on “common ground” with the spirits of those in the past, but also today with like-minded community that includes you. Together we create one more layer to connect us all, from the past, through the present, into the future. WELCOME, Frank Vagnone and Johnny Yeagley!

LikeLike

Welcome! We are glad you are here in Winston-Salem.

LikeLike