“It’s about an hour flight outside of Sydney; then you have to drive to the homestead. It’s kind of out of the way, but well worth it.” That was the bait that lured me into traveling to the Saumarez homestead in New South Wales, Australia to hold a “One-Night Stand.” We had just spent about three weeks traveling through Australia speaking and facilitating workshops for the National Trust of Australia. I was coming off of another “One-Night Stand” at the Iron House in Melbourne and was intrigued by experiencing a more rural sleepover. I said “yes” and the next thing I knew I was standing in the Armidale airport.

Moments later ensconced in a car with a local driver behind the wheel, we rode a bit into the open vista of this agricultural region of Australia. Unexpectedly we turned onto a dirt road, and I was told that this was the homestead’s driveway. I kept waiting for the house to come into view. I waited. Waited some more. I finally took out my smartphone and started to film the drive. To say this place was remotely situated is an understatement. Eventually, we entered another gate and the house rested in front of us. Not jaw-dropping imposing, but beautiful. The car stopped, and we got out.

The sun was crisp and what became clear at that point was the intensity of the long horizontal vista of the slightly rolling landscape. The Australian sky felt very large and in control. The house was merely a small bit player in this theater. This experience was made more intense from the fact that we just had just spent a few weeks in dense urban cities where there is an almost complete absence of a vista or horizon. What was already clear to me was that this historic site was all about the landscape the relationship to it.

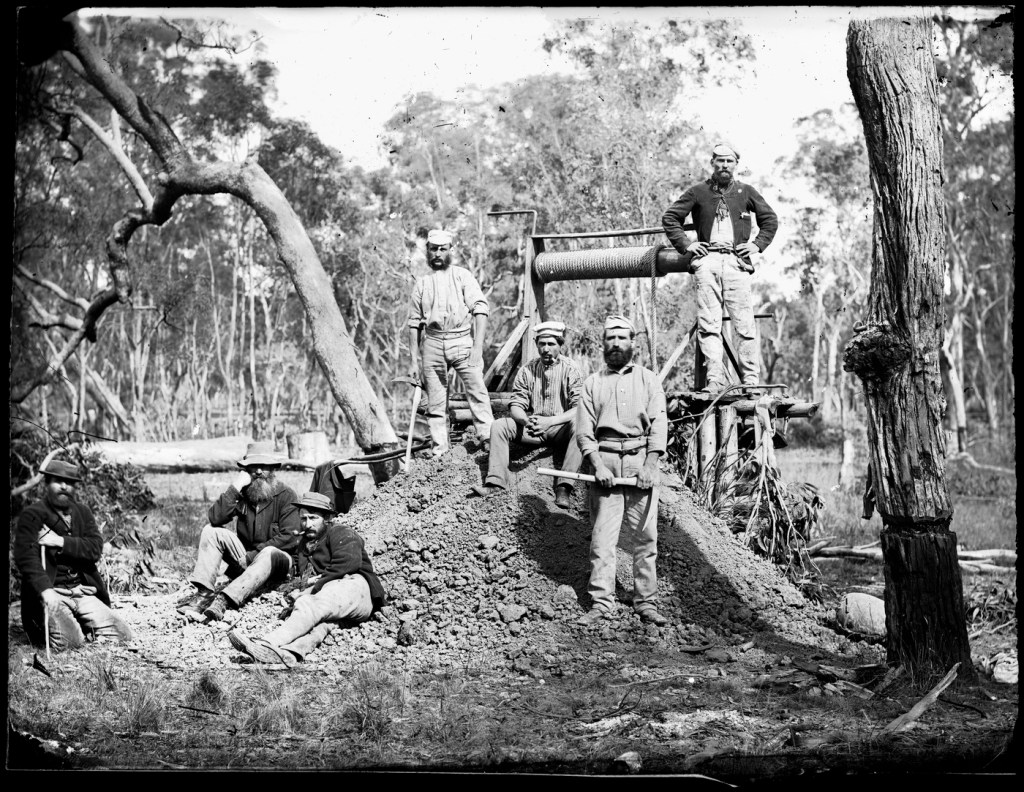

Saumarez Homestead was once an enormous 100,000-acre grazing property. Originally land occupied by the Aboriginal peoples, it was later first inhabited by British settlers in the 1830’s. The location was considered the last stop before traveling north “beyond the boundaries” of British civilization. The property was inhabited by several families up to 1984 when it was donated to the National Trust of Australia.

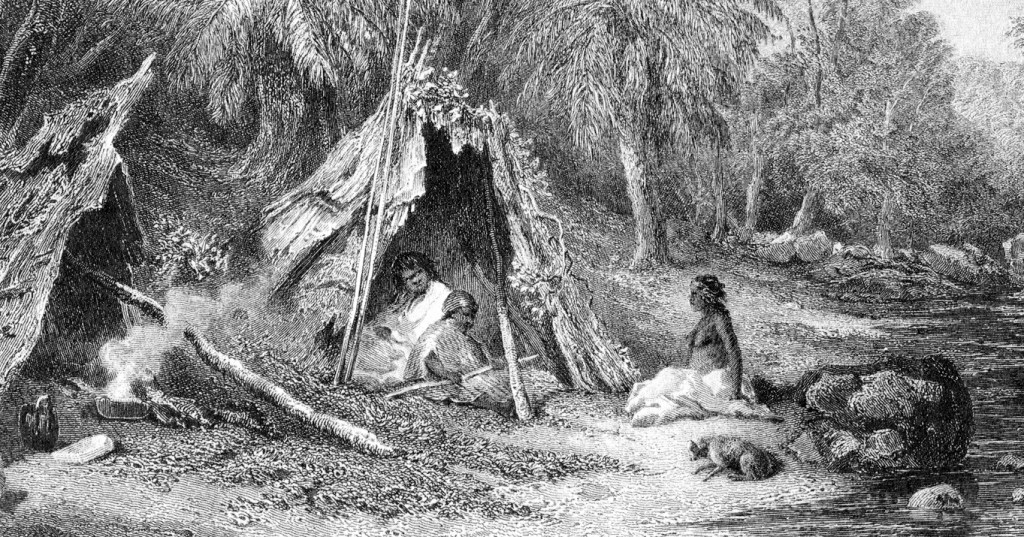

Prior to the British colonizers, the Anewan (Anaiwan/Anaywan) were the traditional occupiers of the land around the town of Armidale and the New England tableware in New South Wales, Australia. Collectively the lands measured about 3,200 square miles. The Anewan consisted of four clans, 1. Irong; 2. Arpong; 3. Lyong; and 4. the Imbong. The Irong intermarried with the Lyong and the Arpong with the Imbong. As was the case in almost all of Australia, the British forcibly moved and contained Aboriginal populations into tighter and tighter areas. By 1903 the remnants of the original tribes who occupied the land area around Saumarez had been relegated to the fringe of town in an area called “The Dump.” By the late 1940’s the area was still occupied by about 80 families living in humpies (shacks) built close to the trash heaps, which were absent of water, sewerage, and electricity. They were constructed of throw-away materials like hessian bags, corrugated sheet iron, and cardboard boxes. Eventually, these were replaced by brick units in a settlement which the local Aboriginal reservation named Narwan.

Knowing this history of colonization in the New South Wales area of Australia, we stepped out of the car expecting a severe landscape scarred by history. Instead, we were greeted by a world of thriving green plant life, vibrantly singing flowers and a chorus of flying insects dancing from blossom to blossom. It was almost too much to take in at one time. I just stood there, squinted my eyes from the sun and tried to separate all of the enmeshed plant life into discernable and understandable specimens.

It was impossible; everything was in a continuous, intertwined state of growth, bloom, and death. The smells of the landscape were spectacular. I have never really thought about the intangible element of smell as a part of heritage. Everything seemed big and alive. I didn’t feel like this heritage site was about history – I felt like it was about the present. As is often the case when I visit heritage sites, I have difficulty reconciling the full history (which in this case contains genocide) with the beauty and loveliness of the setting. In fact, the loveliness of the setting most likely had something to do with the initial push to remove the Aboriginal peoples from the land that now is Saumarez Homestead.

Almost immediately our host escorted us to a side garden where he told us to sit while he prepared our lunch. We offered to help him, but he insisted that we rest quietly and experience the garden. As we sat, we looked around and took notice of all of the delicate still life scenarios that surrounded us. It felt like a theater set orchestrated for just our moment in the garden. The food seemed a direct descendant of those populating the garden. The greens and colors of the salads spoke the same language of the garden plants.

As we ate lunch, we discussed Saumarez, its history, and present heritage site stewardship issues. Its remoteness not only was its charm; it was its primary liability. Once you arrived, the journey was worth it – but getting there was the task. I was eager to discover the other charms of Saumarez beyond its landscape.

Following our lunchtime discussion, we were left to roam the site and experience the house and grounds on our own. It is a large parcel of land so wandering about was no problem. In fact, it was exciting to peek and explore out-of-the-way gardens, farm buildings, and abandoned areas. This self-direction was perfect for the Saumarez site. As I walked, I noticed overgrown ponds, gravel walkways, fences holding in an exclusive area, and rusty long-ago-used farm equipment. One fenced area opens up to another. The homestead seems to take on multiple meanings for me. Not only does it stand as a remnant of a historical period of agriculture, but takes on a symbolic stand defining the era of British colonialization and suppression of the aboriginal peoples. The way the land is divided, fenced, and contained seems like a direct a front to the massive vistas of the Australian horizon. At what cost all of this beauty and tranquility?

Outbuildings were seemingly randomly placed throughout the landscape as if to now be a shadow of a previous existence where its functional placement, now lost to our understanding, was needed and designated in just that spot. This site had a lot to tell me about its past and how it is kept in its present state. The homestead vibrated with energy and growth. I particularly liked when the sprawling agriculturally-built environment could be seen encroaching in on the more formal main house. It was almost as if there were two types of landscape: the approved, and then that of the needed but unrestricted latent farm landscaped. The back of the house had a seemingly haphazard accretion of uses and forms that sat smoothly next to automobiles, garden equipment and the detritus of everyday upkeep. This dichotomy was meaningful and cogent.

Our exploration ended up in the back-mudroom of the main house. We wanted to get settled in our room before the sunset so we headed into the formal stair hall and upstairs to our bedroom. I stopped along the way to peek inside of each room. The sun was very bright outside, but inside was dramatically dark and contained. I could imagine in the heat of the summer the dark house would be very welcomed and cool respite.

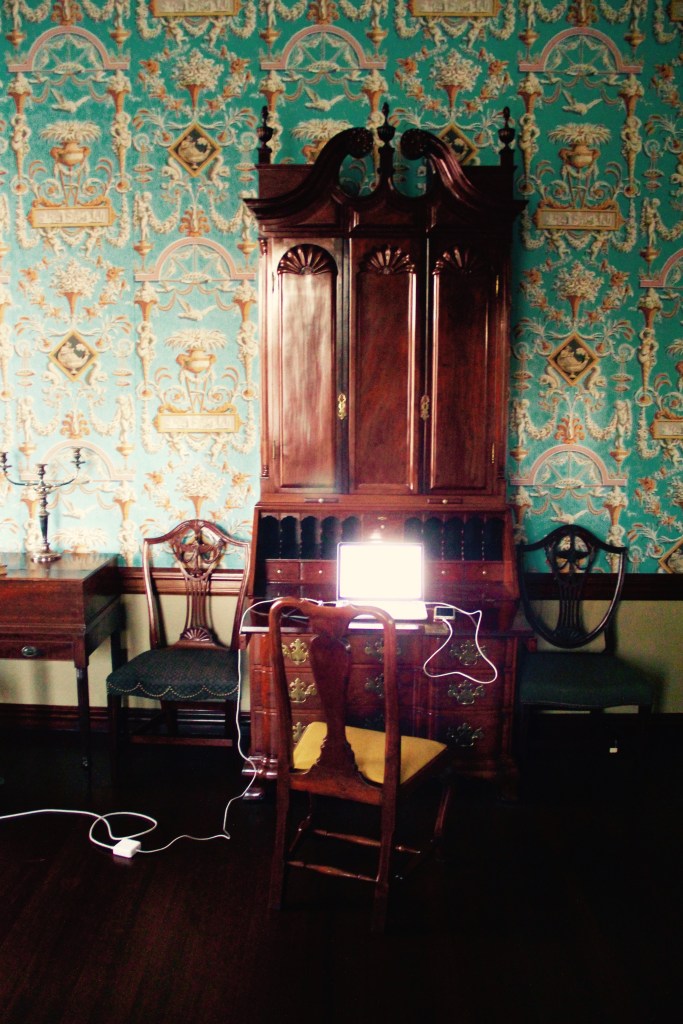

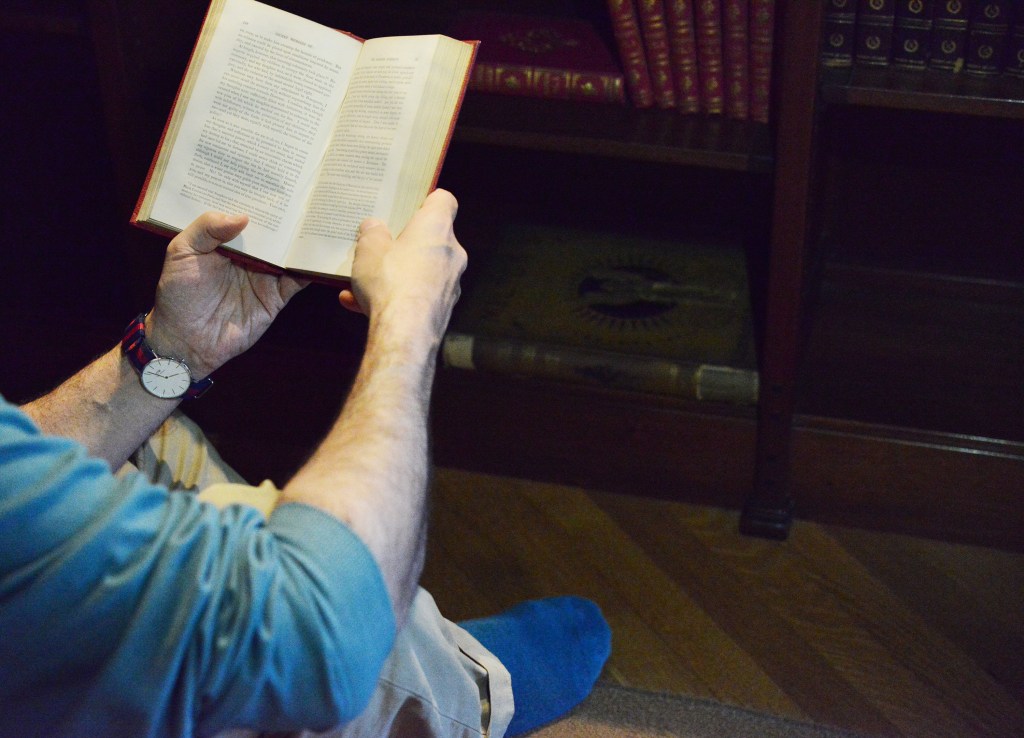

Walking up the grand staircase, I witnessed the second -floor hallway spaces blossom into a centralized open space, oozing out to large porches with deep overhangs. The bedrooms spiraled around this ample open space and each bedroom came equipped with its own sleeping porch area. The interior didn’t seem overly scrubbed by preservationists or overly curated. The spaces had a very lovely worn feel about them. We made it to our bedroom, dropped our bags, and I set up my computer.

My attention to the interior of the house was seriously re-directed by the setting sun. I felt like the sky was making another plea for attention. I ran out of the house, into the tree-lined, entrance drive courtyard, and out onto one of the fenced in pastures. I stood there for a few minutes, once again trying to grasp what I was seeing. The sunset and the landscape were so astoundingly picturesque that I consciously distrusted my eyes. I squinted and looked again. Nope, not #FakeNews. This was the real deal. The vast Australian landscape that I had been told about was right in front of me.

The sun set below the pasture, and it became void and dark. The sounds changed from birds chirping to sounds emanating from animals that I couldn’t recognize. The sky was wholly saturated with stars. Once again, I stood in amazement as to what I was seeing. As a resident of New York City, it is rare if I see any stars in the sky, so this experience was made all the more startling for me as my eyes adjusted to the darkness and my night time galaxy guests arrived. I walked onto the open -air porch, pulled the front door open, walked in and shut the door.

I headed back upstairs to finish organizing my bedroom and desk. I also wanted to take a bath before dinner so I figured out how to achieve a hot wash. The bathroom was a large, uncomfortably tall space. I felt like a little kid playing in the bathtub. It came equipped with an antiquated shower head, but clearly, it didn’t work because our host left a large water pitcher for us to use. The water was quite hot and the bath offered a very welcomed few minutes of quiet. I am not ashamed to say that the heated bath, along with my jet lag, made me tired. After getting dressed, we headed down to the dining room for dinner (and of course after, the washing of the dinner plates).

The day of exploration, the wonderfully warm bath, and the delectable dinner made me feel very relaxed. It didn’t take long for me to fall sound asleep. Being so isolated and far out in the countryside, I imagined that I would find it hard to go to sleep, but the opposite was the truth. This vast estate seemed like a cocoon. As quickly as I went to sleep, my alarm prodded me up before sunrise. I Iike to catch the light through the windows and experience how a house wakes up.

One of the most remarkable experiences I had that morning was walking out onto the second-floor stair hall balcony and listening to the landscape become animate again. I stood there in my bare feet, once again perplexed by the sounds and smells of the estate. As I look back on it now, that moment the real experience of the Saumarez Homestead. This heritage site lives within the space of the past and the present. It allows you to inhabit today’s animate landscape at the same time as you garner hints at the previous life of the land. I imagine that the same sounds that I heard that sunrise morning were the same that those who lived in the house a hundred years ago heard. The porches act as a mediating zone between the history of the house itself and the future as externalized in the landscape.

Compelled by the beauty of the homestead’s natural environment, I delved into researching the indigenous Australian landscape. Ironically, when the British began colonizing this area of Australia, they cleared the lands of mostly eucalyptus trees so that the sheep could graze. In an attempt to make their new land much like Britain, they imported massive amounts of flora that was previously not grown on the island. Both of these actions forever altered the natural landscape and instigated a cascading effect of changes that in many ways made it impossible for the Aboriginal peoples to continue living their lives in the manner they were accustomed.

It is estimated that about 40% of all Australia’s forests have been cleared to make way for grazing and other forms of agriculture. Species of an animal were introduced in such quantities that the natural ecosystem was shifted in such ways that food-producing animals for the Aboriginal were lost in favor of other species more beneficial to the British.

This is a fascinating quality about this landscape: the abundance of lush green spaces and beautiful flowers and garden are actually the results of colonial dominance over a naturally harsh landscape. The very notion of a “garden” is in itself an act of control. It does take a bit of intention for me to be reminded that the beauty of the flowers is a mechanism to assure pollination – Beauty is not an end in itself.

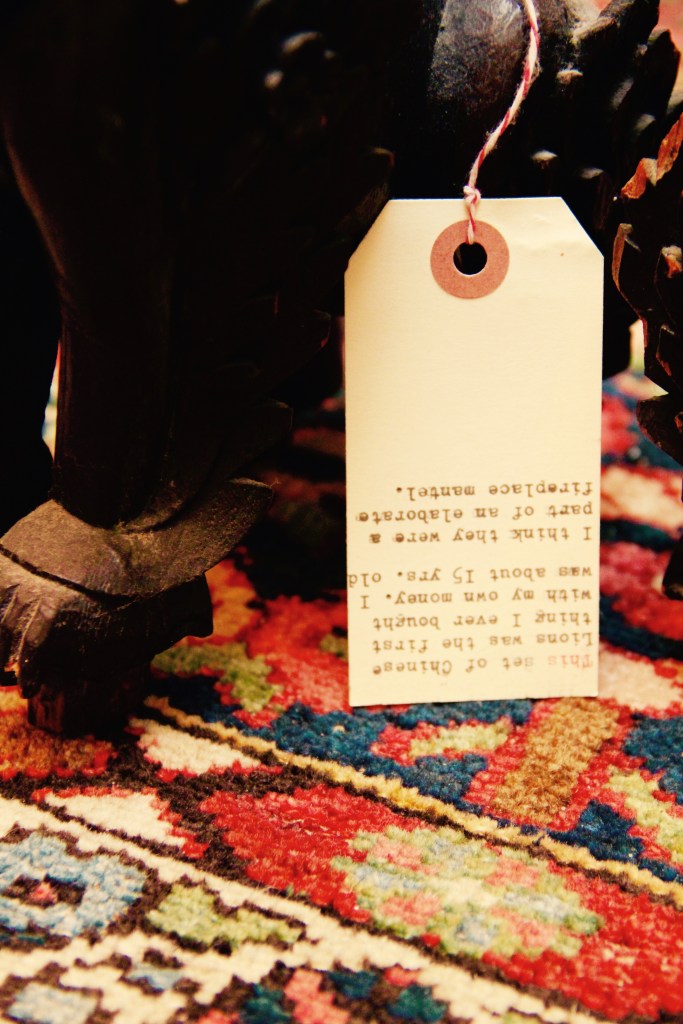

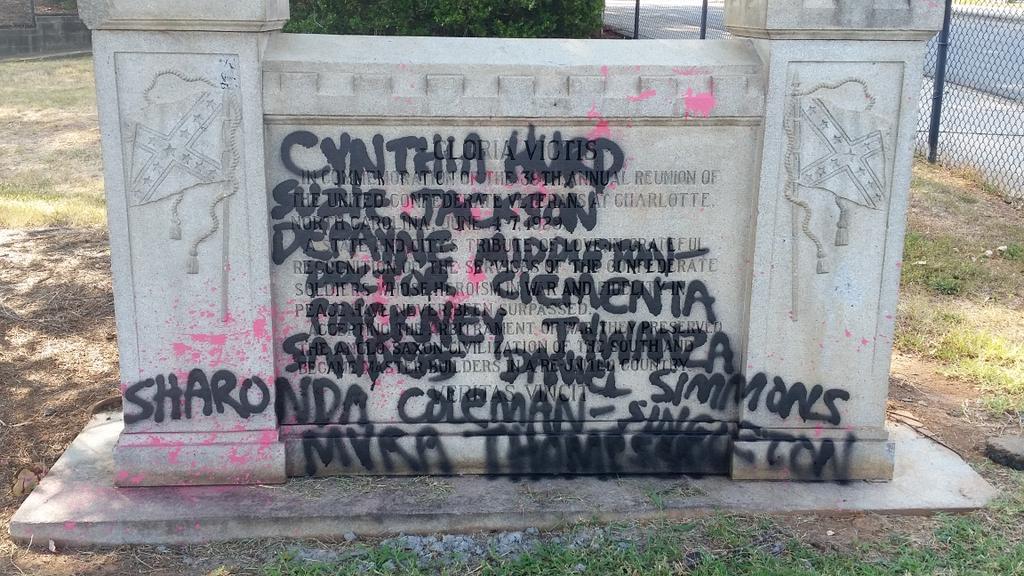

As you walked through the landscape and house, you take notice of all of the family’s accumulated possessions. You occasionally see objects of colonialization: a British flag, a favored UK food, or an image of the Queen. These items are important. They are memorials if interpreted well, capable of producing a landscape of dialogue and debate. Removing the artifact simply means that there will be nothing against which to focus our understanding of the flaws and biases. They stand as records and archives of things that, without the physical forms, would quickly disappear from our memory – and thus, our decision-making process.

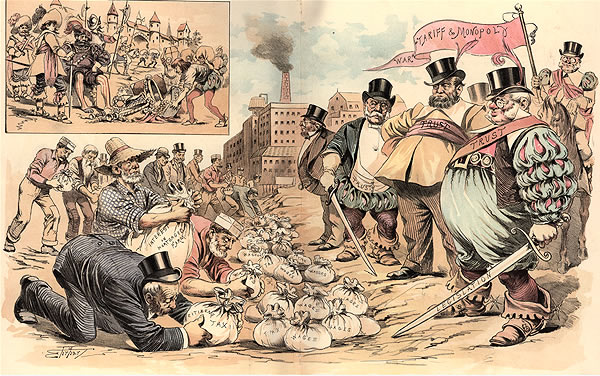

Many social commentators are suggesting that the world is now fully entering into a second “Gilded” or “Edwardian” Age. The amount of collected wealth in a few is producing a built environment full of massive estates and new forms of “colonization.” I wonder if looking back one hundred years – as I am doing at Saumarez now – will give us clues to the push and pull of economic and social constructs? Will the heritage sites from today’s era be interpreted in a way that manifests the abrasive realities of our world? Or will they be beautiful landscapes and well-curated historic house museums that glazing over the fractured cake that lies underneath that beautiful icing? What part might a site like Saumarez Homestead play in our understanding of this socio-economic situation?

As is usual with heritage sites that I visit, the real story is somewhere behind the glamour of the Edwardian Gilded Age big house or found in a tertiary family member. For the Saumarez Homestead, the real story lies in a small three- room brick slab building hidden among the disparate, aging farm buildings a short walk from the big main house. This simple structure is an isolated shadow of a complicated ownership process beginning with the Colonel Henry Dumaresq, who came to New South Wales in 1825, then to Henry Thomas 1856, and finally the White family in 1874.

The Dumaresq homestead started out as one of the very earliest English settlements in New South Wales. The land area housed about 16000 sheep, 1600 cattle and was managed by about 24 working men. The family built a small slab building and a handful of agricultural farm buildings.

Following the sale of the land in 1856 to Henry Thomas (born in British India), the Thomas family built a brick cottage addition to the previous Dumaresq building. The original Dumaresq building is no longer extant, but the Thomas addition is still standing. This house is a small, out-of-the-way brick building on the present Saumarez homestead site. In this quiet structure is the real story of British colonization.

The original brick homesteading house looks much like a streamlined RV with tent awnings pulled out from the brick core. It is much smaller than the later main house; with its curved tent-like roof, it feels more like a temporary place of habitation than a permanent home.

As I rested in the curving voluminous billowing porch of the house, I closed my eyes and listened to expansive songs of the birds and inhaled the alchemic scents of the plant material surrounding me. It was peaceful and introspective. How did this non-descript slab house play a part in the more extensive process of economic and political domination throughout the Gilded Age? This process of economic maturity seems to be at the core of this heritage site. The families and individual members of those families seem to me to be merely small specs in a windstorm of cultural change.

In some ways that very quality is the reason to visit this heritage site – if allowed, this site can be quiet enough to whisper to you a fuller story of Australia; a story of its beauty as well as its historically destructive cultural forces. Ultimately, it can share with you what it meant to live as a small player within a larger privileged system.

Ironically, the stewards of Saumarez understand the need for inclusion and expansion of the visitor engagement for the site. A few months after our visit I received an email from our host. He wanted to tell me about a new project he had initiated. He invited traveling RV owners to come to the homestead and form a caravan on the farm property. He attached a few pictures showing how he allowed the RVs to be parked fully integrated with the historic farm landscape. There, right next to one of the tiny, original colonial dwellings, are a handful of mobile RVs. In some ways, you have to look twice to distinguish between the permanent and the temporary dwellings.

The stewards of the homestead understand that their remoteness is one of the liabilities to increased community engagement. Because of this challenge, they are attempting to change the standard model of visitation. So, successful was this first attempt that they are considering expanding the pilot project into a regular visitation event. This type of reconsideration of a standard model of practice is precisely the area that can be so fertile for heritage sites. Seeing change not as something forced upon the site, but as an opportunity to remake what the homestead can be to visitors, is the core of a successful future for any heritage site.

If judged by the usual historic house museum standards, Saumarez Homestead is quite pleasant enough as a building and collection. It is, however, significantly superior in providing a contextual understanding of British colonialization and the relationship of the landscape to those who inhabit it. We can ascertain this relationship more clearly out in Armidale than in denser and overbuilt megacities like Sydney and Melbourne. For me, the meaningful story here is the superimposition of the British culture on top of the existing Aboriginal populations. This narrative has much to say to us today and how we respond to issues like immigration, nationalization, and refugees.

That is one reason is why I find the mobile RV caravan camps so appealing for this site. It symbolically proclaims a sort of temporary “colonization” upon an established site and allows a culture to overtake and/or blend with an existing framework. I think this is a wonderful opportunity for the stewards of Saumarez homestead to re-think the stories and the narrative structure of the site.

Waiting for the car to take us back to the Armidale airport, I rested on the main house porch. What luxury to simply relax in this environment. What privilege. Perhaps that privilege is the substance of this heritage site – are our regular lives so basic, average and mediocre that we seek out these saved spots of privilege so that we can sneak a few minutes of what it would have felt like to be one of the 1%? So many house museums in which I experience “One-Night Stands” are remnants of this Gilded Age period (or another period of privilege) and many times I think how disconnected I feel to the basic premise of sites like these.

True, they hold beauty, but what else can they tell us? Are they merely shrines to a particular family or individual? What I initially experienced as natural landscape beauty at Saumarez, I now see as dominance and colonization. The plant material, the cleared grazing lands, the fenced pastures, and the agricultural and industrial built form of the site all join into a landscape of symbolic meaning and dark shadows. These structures are not merely architecturally significant forms; they stand as a manifestation of power, control, dominance, and suppression.

My time at Saumarez highlighted one of the recurring themes to many of the “One-Night Stand” experiences. The excitement and beauty of a site eventually dissolve in such a way that, if you are seeking such information, deeper layers of experience are revealed to you. The problem that I have long understood is that if you are not interested, or simply unaware of a site deeper meaning, then you head home with only the surface souvenir of beauty. I have stated many times in these blogs that I love pretty things, and visual beauty can be quite moving to me, but I usually can push past this initial stage of appreciation and cut deeper into the cake.

My goal with these ONSs is not to be judgmental or critical of a site’s interpretation of stewardship, rather I am seeking how these sites can teach me how to reach into the less knowledgeable and discussed aspects of the history so that we can utilize our fragile heritage sites in more contemporary and urgently anticipated issues. How can Saumarez Homestead teach me about something other than Saumarez Homestead? Is this even a fair pursuit?

I have begun to think of these One-Night Stands as a series of theoretical scientific experiments whereby I enter into an engagement seeking an, as of yet, unrealized problem. If I have a bias it is that I know these sites have incredible depth and substance, and I want to learn from them and the staffs how this depth can become better communicated. As someone who has long stewarded heritage sites, I know from my experiences that it is never an easy job. In fact, many of the things that keep us from telling greater expansive stories have nothing to do with public history, but rather economics, philanthropy, and management.

The holy grail of public history is how we can both pay for preservation at the same time as presenting the substantive dept. of a heritage sites potential. I often feel like we are a circus act, spinning dishes on poles, trying to keep them all moving at the same speed so that none of the dishes will fall to the concrete floor and shatter. This is a skill that I will always be attempting to master. This sort of skill comes from experience and learning how others are attempting to keep all of the plates spinning. That is why I so appreciate my One-Night Stand experiences. I get to learn from the many skilled museum professionals the “tricks of the trade”.

I have recently become aware of a project in the UK, “KICK THE DUST”, which is a grassroots effort of young people to reevaluate the biases and narratives presented at heritage sites and consider how these sites can inform our present world issues. This seems to me to be a very good and positive effort at keeping the dishes spinning.

So how do we reconcile these things with the resultant beauty and experiences that can be found at sites like Saumarez? Carefully and with deep sincerity as to the causes and motivations that produced such a magnificent and fascinating homestead.

THANK YOU:

Saumarez Homestead Staff & friends

National Trust of Australia

After getting settled into my sleeping porch, my first real interaction with the house was utilitarian. This was a strange feeling: because I was in a house that I thought of as so beautiful, to use it as a house was shocking. I found myself in the same rarefied world that I criticize others for occupying – the world that thinks of historic house museums as pretty dollhouses, not as real places for living. Interestingly, my daughter didn’t have the same reactions. She threw her bag down and began using the house like it was her own. I found myself wanting to tell her “be careful!” and “don’t touch that” and to explain why “this is important.” I needed to give myself an internal slap-down: ease up – it’s just a house.

After getting settled into my sleeping porch, my first real interaction with the house was utilitarian. This was a strange feeling: because I was in a house that I thought of as so beautiful, to use it as a house was shocking. I found myself in the same rarefied world that I criticize others for occupying – the world that thinks of historic house museums as pretty dollhouses, not as real places for living. Interestingly, my daughter didn’t have the same reactions. She threw her bag down and began using the house like it was her own. I found myself wanting to tell her “be careful!” and “don’t touch that” and to explain why “this is important.” I needed to give myself an internal slap-down: ease up – it’s just a house.

As my mind returned to the meal preparation, I needed more light, so I moved closer to the windows. When the food was prepped, we set dinner on the servants’ table. The servants’ dining room is a comfortable bump-out from the kitchen, surrounded on all four sides by windows. It almost felt like we were in an outdoor pavilion. I opened some of the windows and allowed a breeze to enter. I had five dinner guests and a lot of food. After we sat down, I toasted my generous hosts. It was nice having my friends from the Gamble House and my daughter share the meal with me. The house faded away as my guests and I chatted about life. No mention of the Gambles, nor the Arts & Crafts movement.

As my mind returned to the meal preparation, I needed more light, so I moved closer to the windows. When the food was prepped, we set dinner on the servants’ table. The servants’ dining room is a comfortable bump-out from the kitchen, surrounded on all four sides by windows. It almost felt like we were in an outdoor pavilion. I opened some of the windows and allowed a breeze to enter. I had five dinner guests and a lot of food. After we sat down, I toasted my generous hosts. It was nice having my friends from the Gamble House and my daughter share the meal with me. The house faded away as my guests and I chatted about life. No mention of the Gambles, nor the Arts & Crafts movement.

When I had opened every window and every door, the sun streamed into the core of the house and the wind blew from the front of the house straight through to the back terrace. You could hear the water fountain in the back all the way to the front porch. To my amazement, the house transformed from a solid, jeweled, safety box into an open-air, stick-built tree house. The entire first floor dissolved into a continuous flow from the green front lawn, past the wide stair, out onto the terrace. A funny thing happened that I think is quite telling. In the middle of this transformation, a couple walked up to the front door area (now simply a series of columns with no barrier) and introduced themselves. I was sitting on the stair landing breathing in the new life of the house. I asked them to join us. We chatted and I invited them back when the house was “open.” Funny, yes, the house was more open at that moment than when they would return to visit it later!

When I had opened every window and every door, the sun streamed into the core of the house and the wind blew from the front of the house straight through to the back terrace. You could hear the water fountain in the back all the way to the front porch. To my amazement, the house transformed from a solid, jeweled, safety box into an open-air, stick-built tree house. The entire first floor dissolved into a continuous flow from the green front lawn, past the wide stair, out onto the terrace. A funny thing happened that I think is quite telling. In the middle of this transformation, a couple walked up to the front door area (now simply a series of columns with no barrier) and introduced themselves. I was sitting on the stair landing breathing in the new life of the house. I asked them to join us. We chatted and I invited them back when the house was “open.” Funny, yes, the house was more open at that moment than when they would return to visit it later!

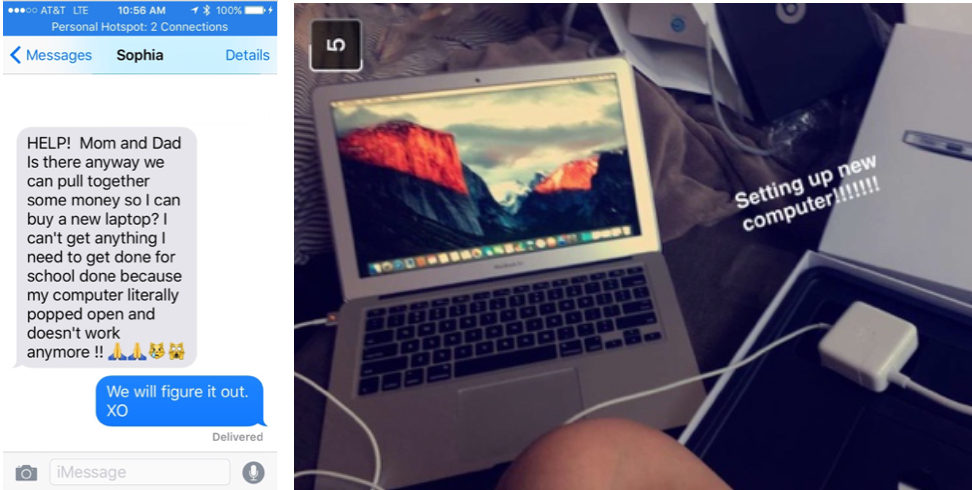

Maybe my issue with house museums is not that they have become less accomplished or beautiful, it’s just that what mattered before matters differently now. My daughter Sophia made that perfectly clear when she asked about the rainforest wood. It’s not that we are ignoring that past, it’s more like we are now interested in embracing another, additional past. The Gamble House hasn’t become ugly or any less meaningful, What has changed is the language with which that beauty and meaning are communicated. It’s not the thing that has changed – we have.

Maybe my issue with house museums is not that they have become less accomplished or beautiful, it’s just that what mattered before matters differently now. My daughter Sophia made that perfectly clear when she asked about the rainforest wood. It’s not that we are ignoring that past, it’s more like we are now interested in embracing another, additional past. The Gamble House hasn’t become ugly or any less meaningful, What has changed is the language with which that beauty and meaning are communicated. It’s not the thing that has changed – we have. As my daughter and I sat on the front porch of the house, watching the cars drive by (including a Rose Bowl Parade float that paraded by), I looked back through the stair hall and out the other side onto the terrace. The house, for me, had broken through the two-dimensionality of its iconic image and blossomed into a three-dimensional, spatial entity. I think, for all of us, there is a moment when in maturity we understand the word around us, not from a distance (in admiration of the great), but rather immersed within its messy, complex structure. We begin to understand that the three-dimensionality of life propels us forward and keeps us alive and aware of shadows and situations that, when younger, we didn’t even know existed.

As my daughter and I sat on the front porch of the house, watching the cars drive by (including a Rose Bowl Parade float that paraded by), I looked back through the stair hall and out the other side onto the terrace. The house, for me, had broken through the two-dimensionality of its iconic image and blossomed into a three-dimensional, spatial entity. I think, for all of us, there is a moment when in maturity we understand the word around us, not from a distance (in admiration of the great), but rather immersed within its messy, complex structure. We begin to understand that the three-dimensionality of life propels us forward and keeps us alive and aware of shadows and situations that, when younger, we didn’t even know existed.

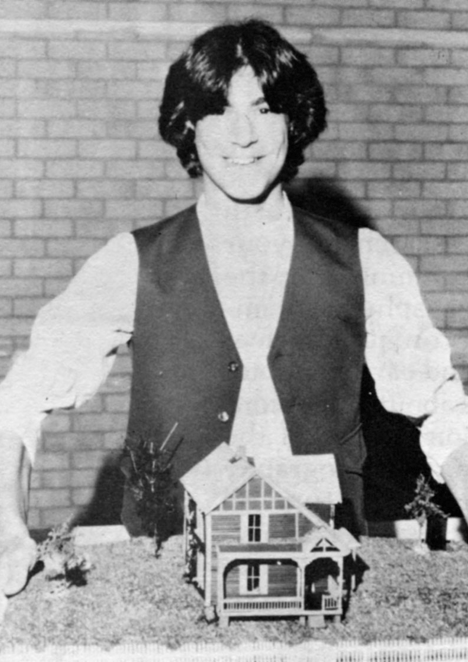

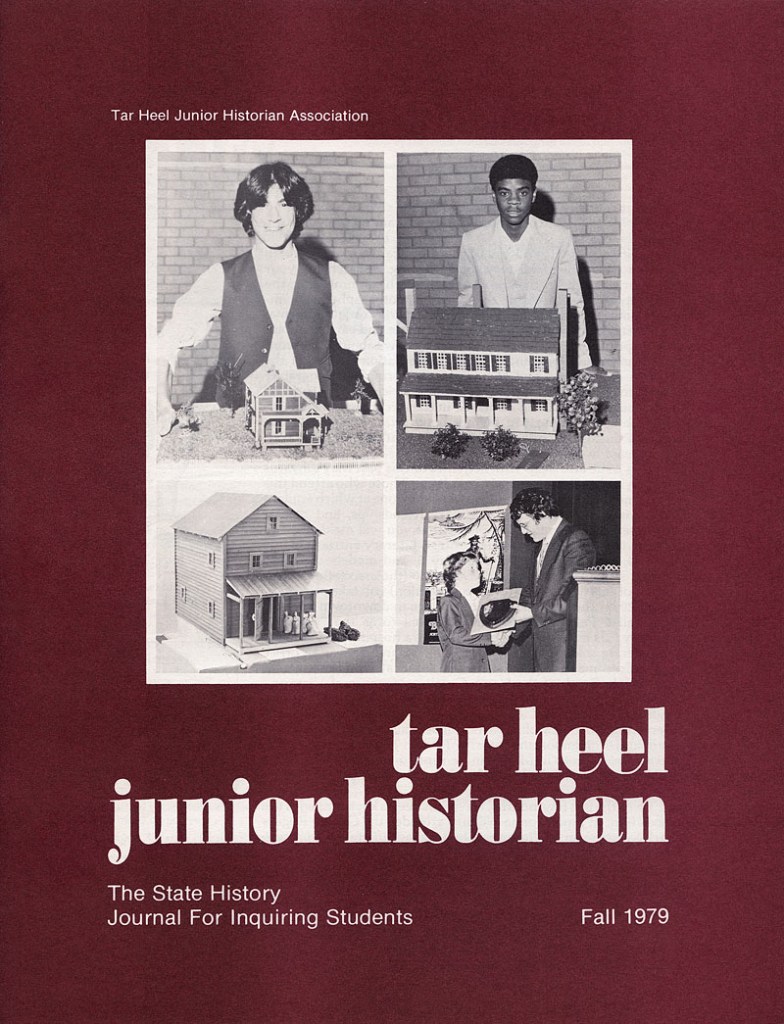

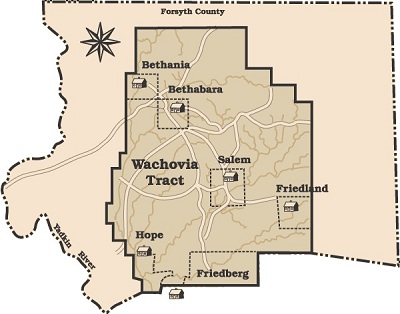

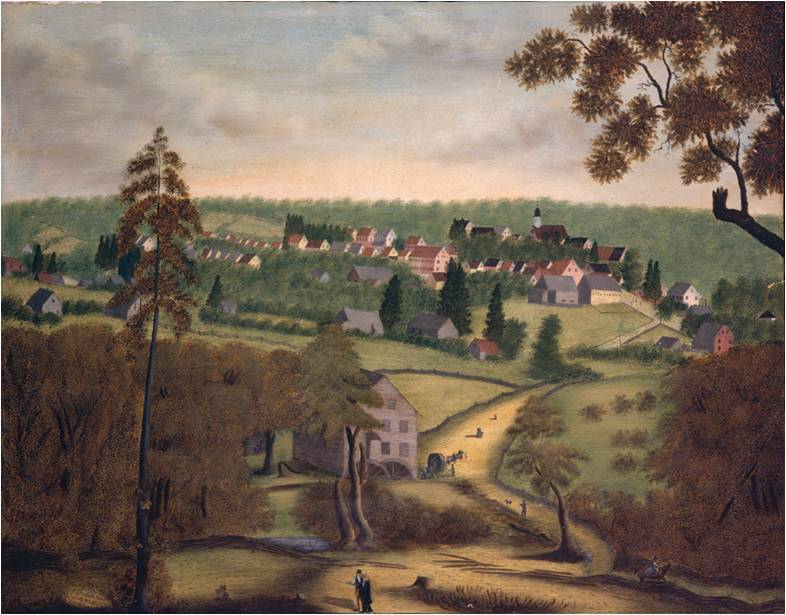

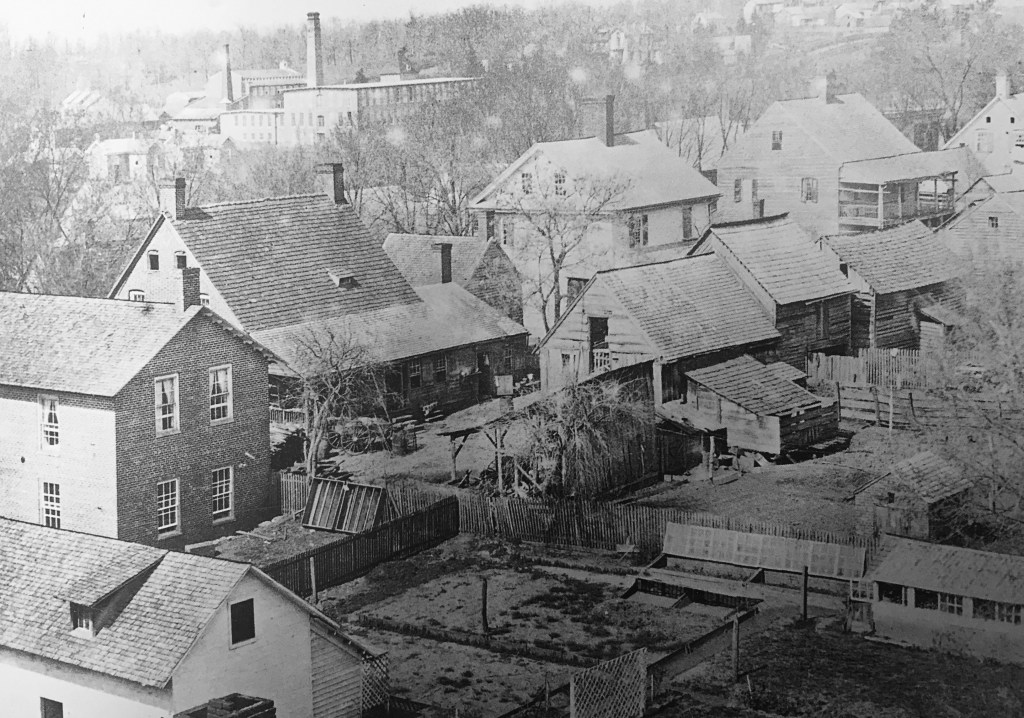

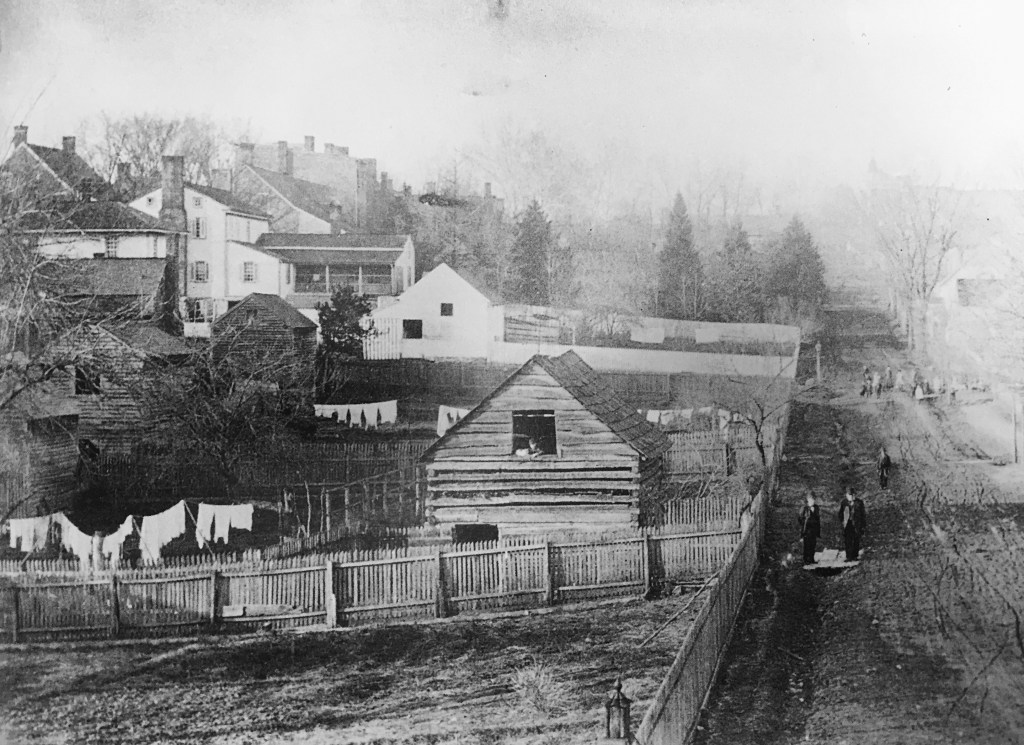

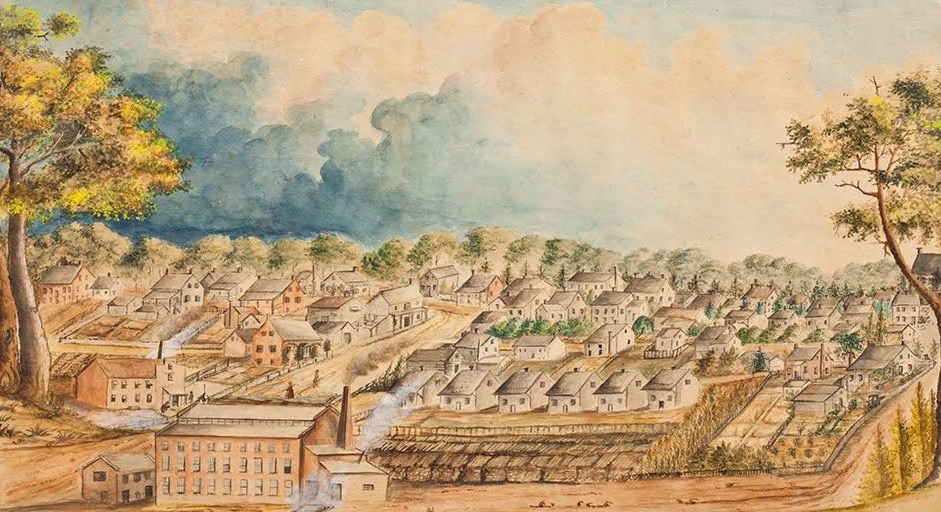

Even in the oldest images of Salem, you can still recognize today’s town. You can clearly see Main Street, the Home Moravian Church, and all the dwellings lined up in orderly succession. As a child, I didn’t truly “see” any of this urban morphology. What I remember from my THJH visits to Old Salem are the great sugar cookies and beautiful fall leaves on the big street trees. I didn’t quite get the Moravians and how they fit into the whole revolutionary war, or any understanding of “difficult narratives”, but for a 12-year-old, that was OK; the trip was fun anyway.

Even in the oldest images of Salem, you can still recognize today’s town. You can clearly see Main Street, the Home Moravian Church, and all the dwellings lined up in orderly succession. As a child, I didn’t truly “see” any of this urban morphology. What I remember from my THJH visits to Old Salem are the great sugar cookies and beautiful fall leaves on the big street trees. I didn’t quite get the Moravians and how they fit into the whole revolutionary war, or any understanding of “difficult narratives”, but for a 12-year-old, that was OK; the trip was fun anyway.

So here I find myself again, some 35 years after my initial THJH visit – this time, getting the chance to sleep over in the town’s one and only historic 1784 Tavern! I am initially reminded of my 14-year old self – a young, sometimes confused, and isolated kid. Back then, I had few friends, and I thought I was only person like me. It is not an exaggeration to state that the Tar Heel Junior Historians and by extension, the village of Old Salem, became lifelines for to me, my self-esteem, and my self-value. Suddenly, I realized I could take pride in my talent and aptitude for history and craft-making. These THJH trips nourished my soul when I needed it most, and showed me a world far bigger than my lonely bedroom.

So here I find myself again, some 35 years after my initial THJH visit – this time, getting the chance to sleep over in the town’s one and only historic 1784 Tavern! I am initially reminded of my 14-year old self – a young, sometimes confused, and isolated kid. Back then, I had few friends, and I thought I was only person like me. It is not an exaggeration to state that the Tar Heel Junior Historians and by extension, the village of Old Salem, became lifelines for to me, my self-esteem, and my self-value. Suddenly, I realized I could take pride in my talent and aptitude for history and craft-making. These THJH trips nourished my soul when I needed it most, and showed me a world far bigger than my lonely bedroom.

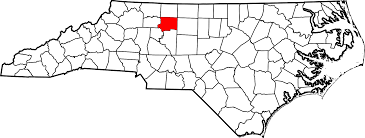

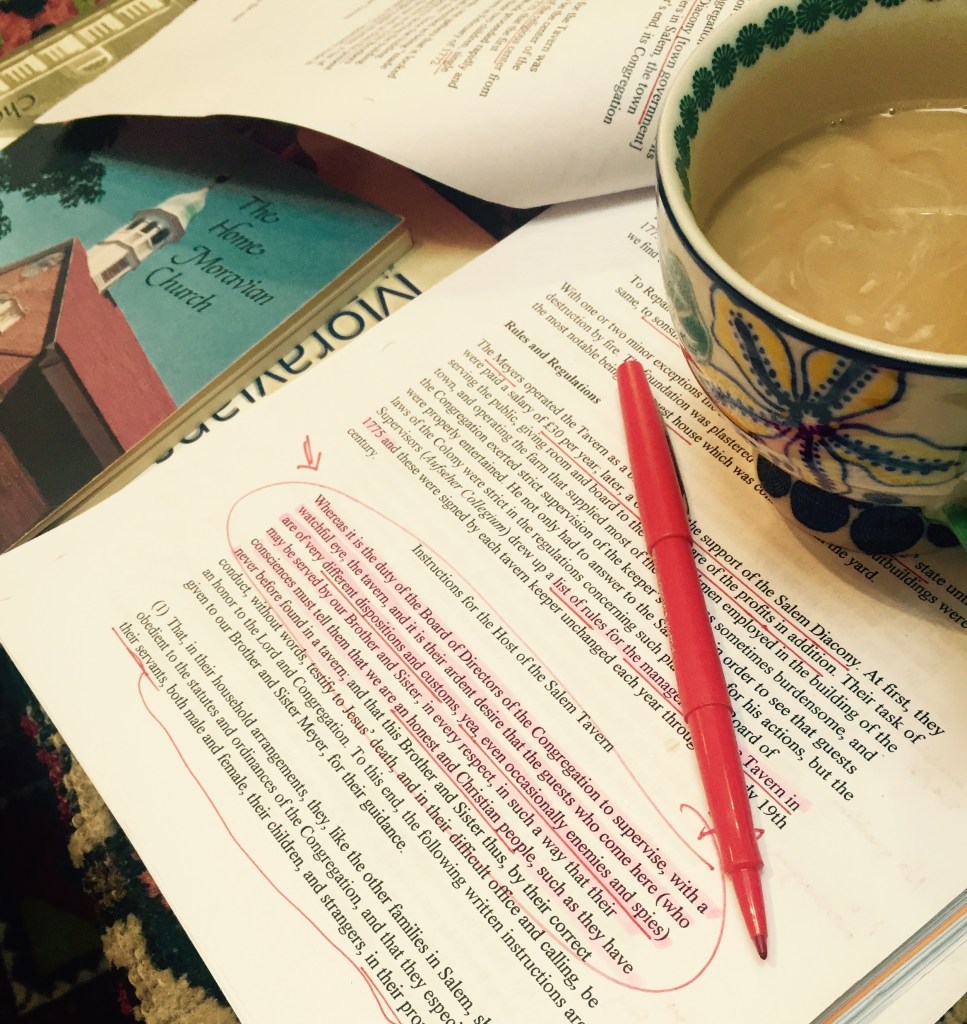

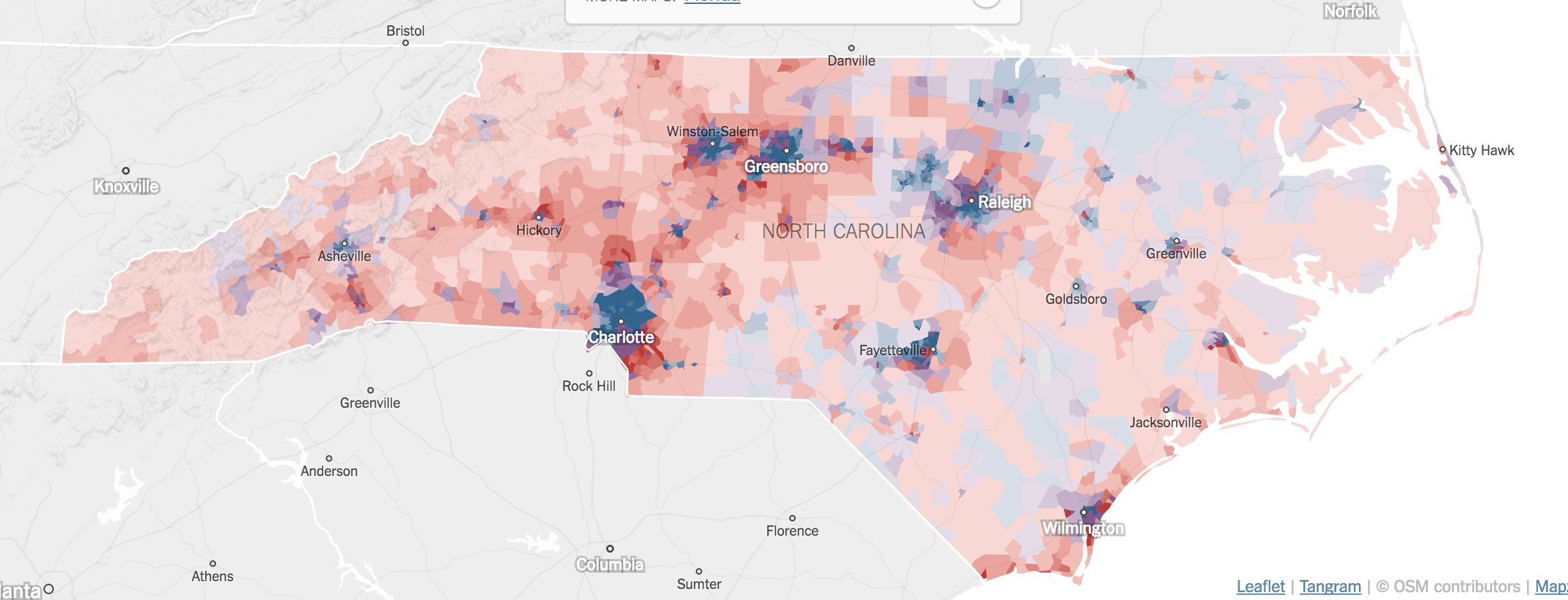

Coming out of the recent U.S. Presidential election, this sentence screamed out to me:” who are of very different dispositions and customs, yea, even occasionally enemies and spies”. Immediately, my perception was realigned. In the middle of the wilderness of late 1700s North America, these reformationist Moravians had established what was easily one of the most progressive towns in all the colonies. Having recently seen the 2016 Presidential election results map of North Carolina, I came to understand that one of the most systemically progressive, liberal areas (shown in purple/blue) in North Carolina is Forsyth County, and its county seat, Winston-Salem. It seemed logical that the forward-thinking Moravians sowed the seeds for this several hundred years prior.

Coming out of the recent U.S. Presidential election, this sentence screamed out to me:” who are of very different dispositions and customs, yea, even occasionally enemies and spies”. Immediately, my perception was realigned. In the middle of the wilderness of late 1700s North America, these reformationist Moravians had established what was easily one of the most progressive towns in all the colonies. Having recently seen the 2016 Presidential election results map of North Carolina, I came to understand that one of the most systemically progressive, liberal areas (shown in purple/blue) in North Carolina is Forsyth County, and its county seat, Winston-Salem. It seemed logical that the forward-thinking Moravians sowed the seeds for this several hundred years prior.

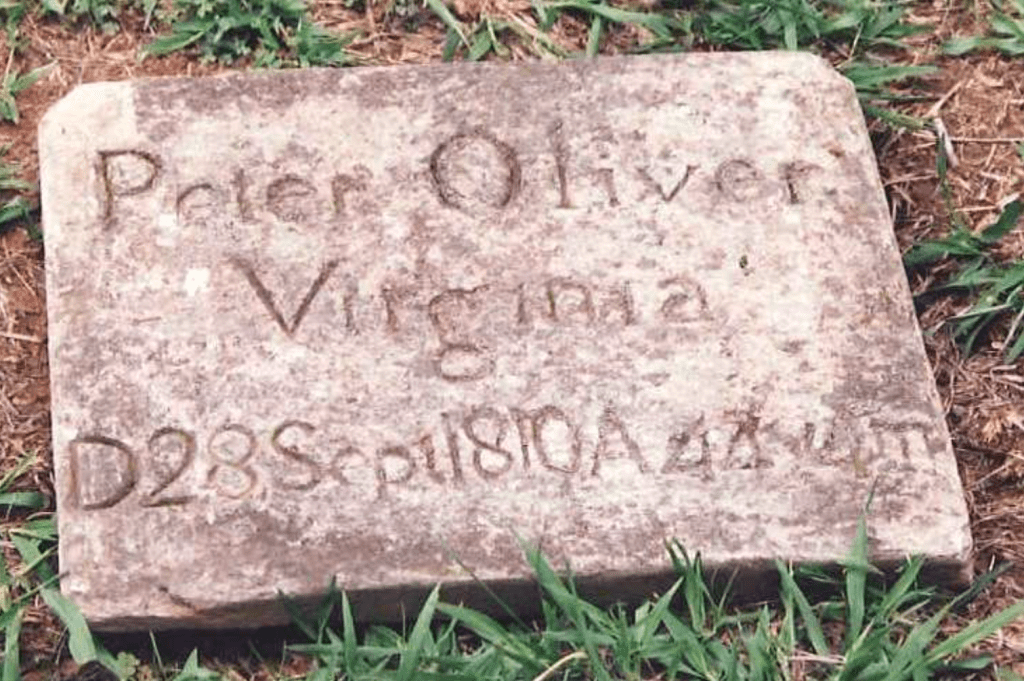

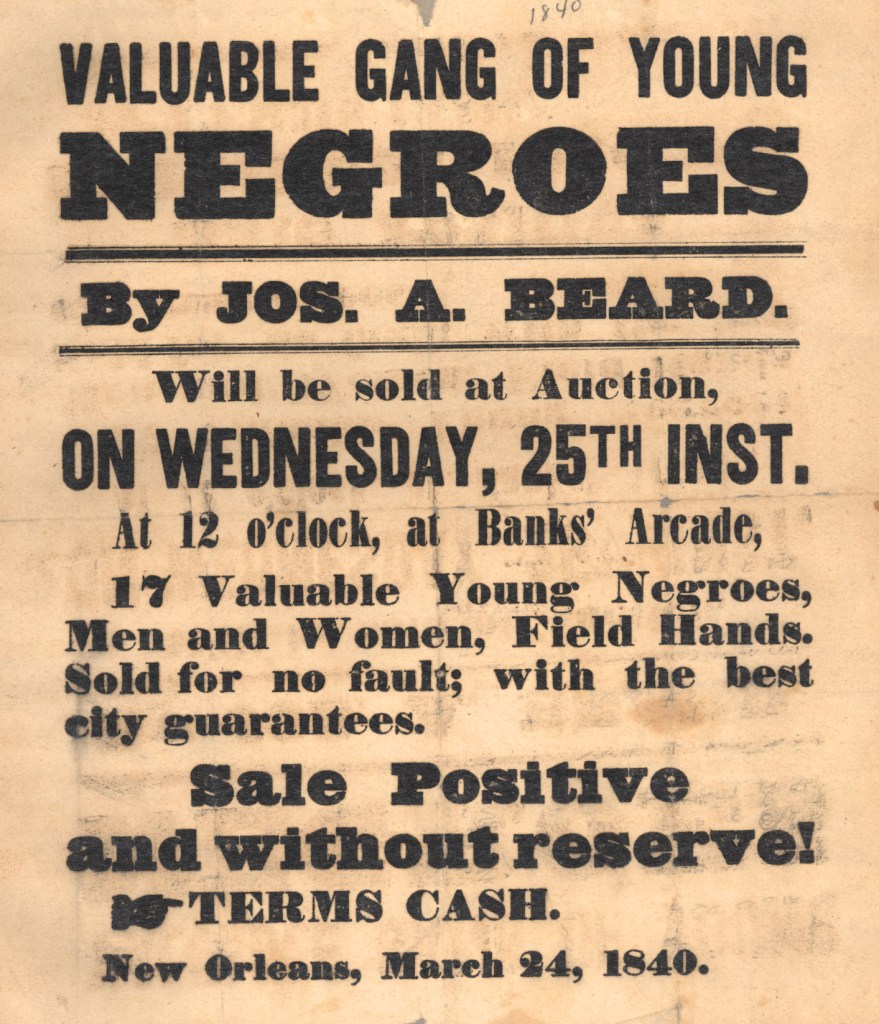

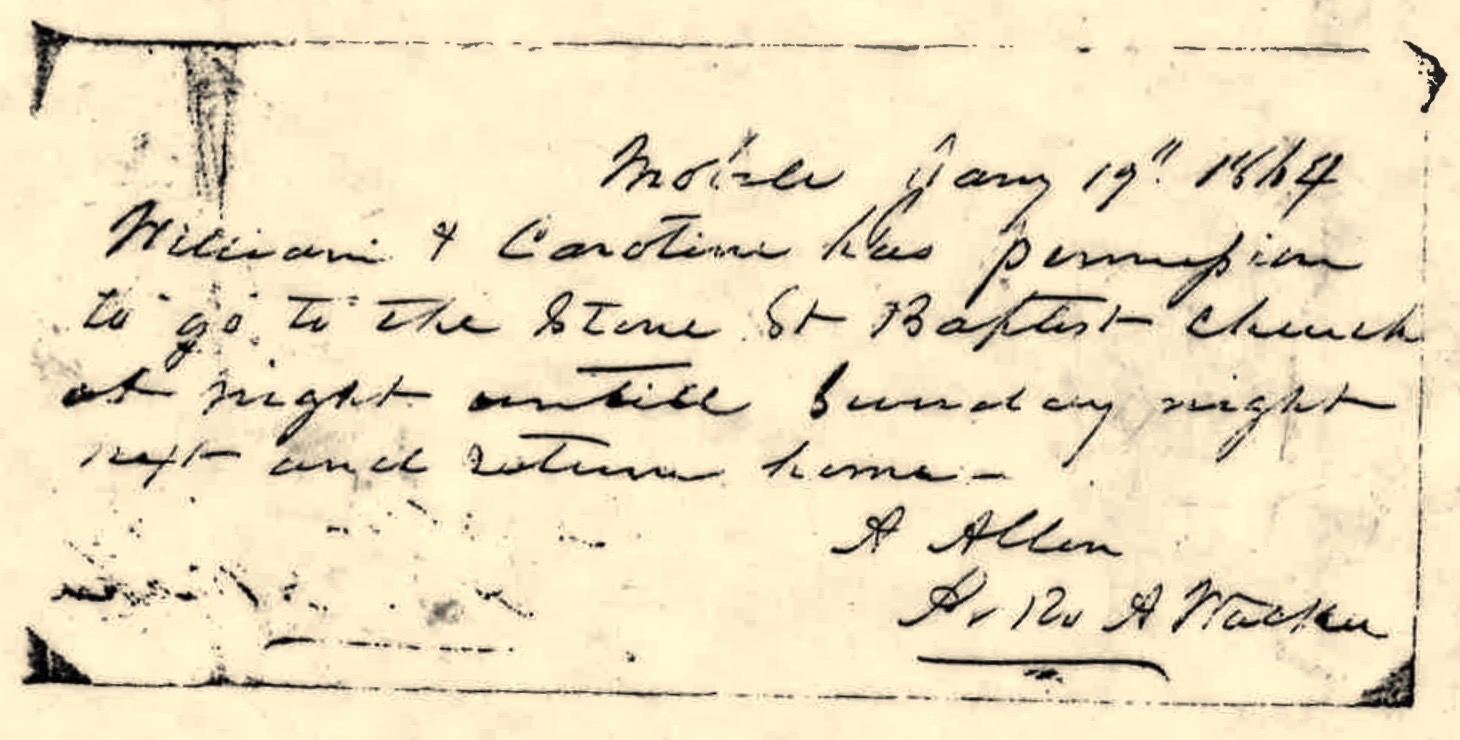

Very early and cursory research has suggested that slave ownership in Salem involved approximately 16% of the town’s free population (1860: 160 enslaved people, 40 slave houses). Though a real and thorough study needs to take place, it appears as if there were 47 enslaved people owned in Salem in the 1840s, down from 83 in the 1830s. The slave population was most likely tied to the Moravian-owned textile mills that were built just north of the town center. While these compelling statistics are being verified, Old Salem has tentatively proposed a long-term archaeological project that incorporates the lot location of owners and the notation of slave houses held by those owners. Because much of the town is original, the potential for archeological information relative to the urban slavery narrative is quite high. This could become one of the most valuable sites for gathering information about slavery in North Carolina.

Very early and cursory research has suggested that slave ownership in Salem involved approximately 16% of the town’s free population (1860: 160 enslaved people, 40 slave houses). Though a real and thorough study needs to take place, it appears as if there were 47 enslaved people owned in Salem in the 1840s, down from 83 in the 1830s. The slave population was most likely tied to the Moravian-owned textile mills that were built just north of the town center. While these compelling statistics are being verified, Old Salem has tentatively proposed a long-term archaeological project that incorporates the lot location of owners and the notation of slave houses held by those owners. Because much of the town is original, the potential for archeological information relative to the urban slavery narrative is quite high. This could become one of the most valuable sites for gathering information about slavery in North Carolina.

The main road, named “Liberia Street,” leads directly down to a footbridge that crosses a creek and leads to the town center of Salem. My host walked me across the footbridge and into Happy Hill. We walked up the main road and stood at the top of the hill. As you stand there, you are struck by how close it is to Salem; in fact, you can see Salem College and other Moravian Church buildings. Looking north and past Old Salem, modern skyscrapers of downtown Winston-Salem looms off in the distance to the east. There’s a clear divide between Happy Hill and the adjacent Old Salem, and it seems so close you could almost throw a rock into Salem Square.

The main road, named “Liberia Street,” leads directly down to a footbridge that crosses a creek and leads to the town center of Salem. My host walked me across the footbridge and into Happy Hill. We walked up the main road and stood at the top of the hill. As you stand there, you are struck by how close it is to Salem; in fact, you can see Salem College and other Moravian Church buildings. Looking north and past Old Salem, modern skyscrapers of downtown Winston-Salem looms off in the distance to the east. There’s a clear divide between Happy Hill and the adjacent Old Salem, and it seems so close you could almost throw a rock into Salem Square.

Just as soon as I had finished cleaning the veggies, I was called upstairs by Earl Williams of the Education Staff – We had to tighten the ropes to my bed and then make the bed.

Just as soon as I had finished cleaning the veggies, I was called upstairs by Earl Williams of the Education Staff – We had to tighten the ropes to my bed and then make the bed.

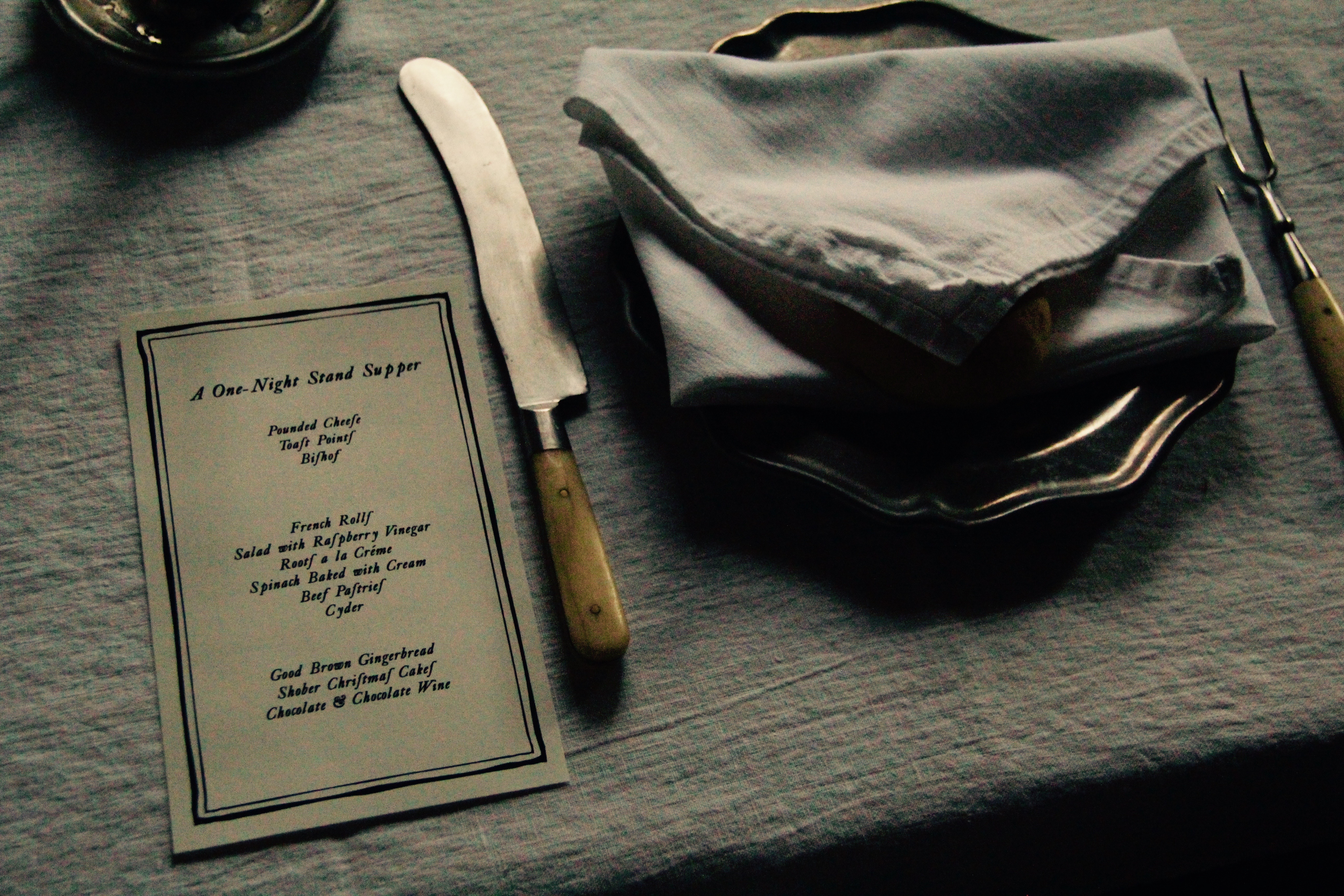

My guests for the dinner included stakeholders from all over Winston-Salem. My request had been that our dinner table represent the community that surrounds the historic site. We had elected officials, an artist/maker, a gentleman who gave the keynote speech for Old Salem’s 2015 Naturalization Ceremony, the Director of the Old Salem African-American Programs, and various board and staff members. As we gathered on the porch of the Tavern, a group of musicians, led by Scott Carpenter, began to play welcoming music.

My guests for the dinner included stakeholders from all over Winston-Salem. My request had been that our dinner table represent the community that surrounds the historic site. We had elected officials, an artist/maker, a gentleman who gave the keynote speech for Old Salem’s 2015 Naturalization Ceremony, the Director of the Old Salem African-American Programs, and various board and staff members. As we gathered on the porch of the Tavern, a group of musicians, led by Scott Carpenter, began to play welcoming music.

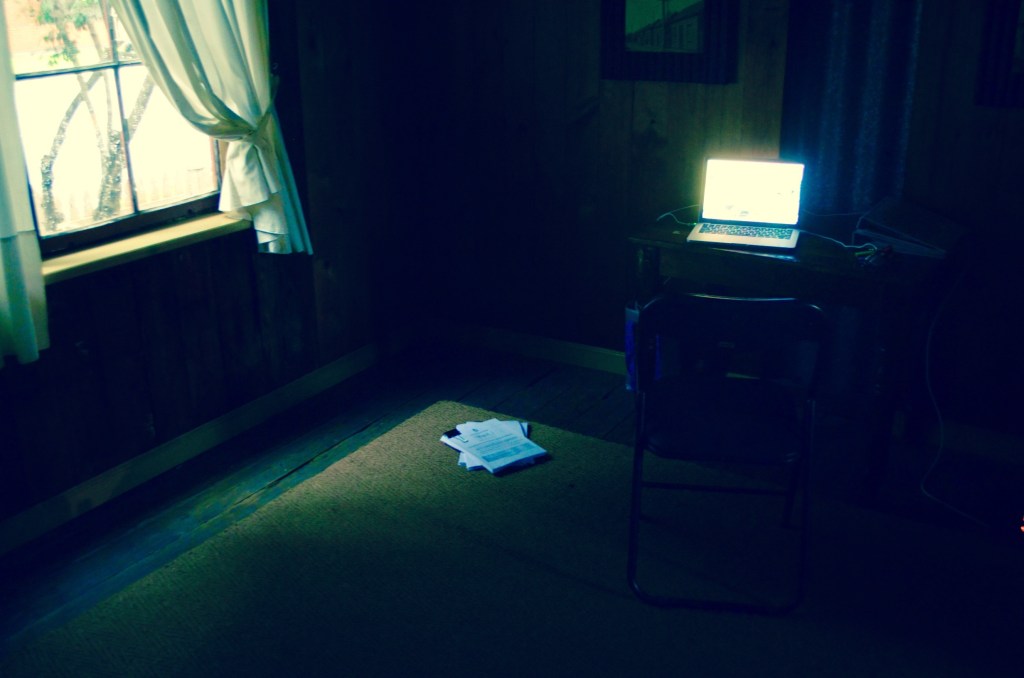

Sitting on the rope bed with my computer, I wrote and uploaded photographs to my social media accounts. It was a bit of a challenge trying to encapsulate the day’s events, especially since so much of what I encountered had upended my preconceptions and expectations. My naïve childhood understanding of Old Salem was forever altered. Forcing a realignment of preconceptions is, in fact, exactly what a historic site can and should do. It can renegotiate what you thought you already knew, and establish a paradigm that you didn’t even know existed. Such is the power of a site like Old Salem.

Sitting on the rope bed with my computer, I wrote and uploaded photographs to my social media accounts. It was a bit of a challenge trying to encapsulate the day’s events, especially since so much of what I encountered had upended my preconceptions and expectations. My naïve childhood understanding of Old Salem was forever altered. Forcing a realignment of preconceptions is, in fact, exactly what a historic site can and should do. It can renegotiate what you thought you already knew, and establish a paradigm that you didn’t even know existed. Such is the power of a site like Old Salem.

Come down to Winston-Salem, North Carolina and visit Johnny, me, and our dog Yogi. Soon the museum anarchist will soon be in the house! In a case of life imitating art, we will be living in an actual historic property called The Fourth House (c. 1767), which is, in fact, the oldest house in Winston-Salem… and keep an eye on what develops at Old Salem Museums & Gardens – they’ve hired me, the Museum Anarchist, as President & CEO. And by hiring me, they have made it 100% clear, they mean business.

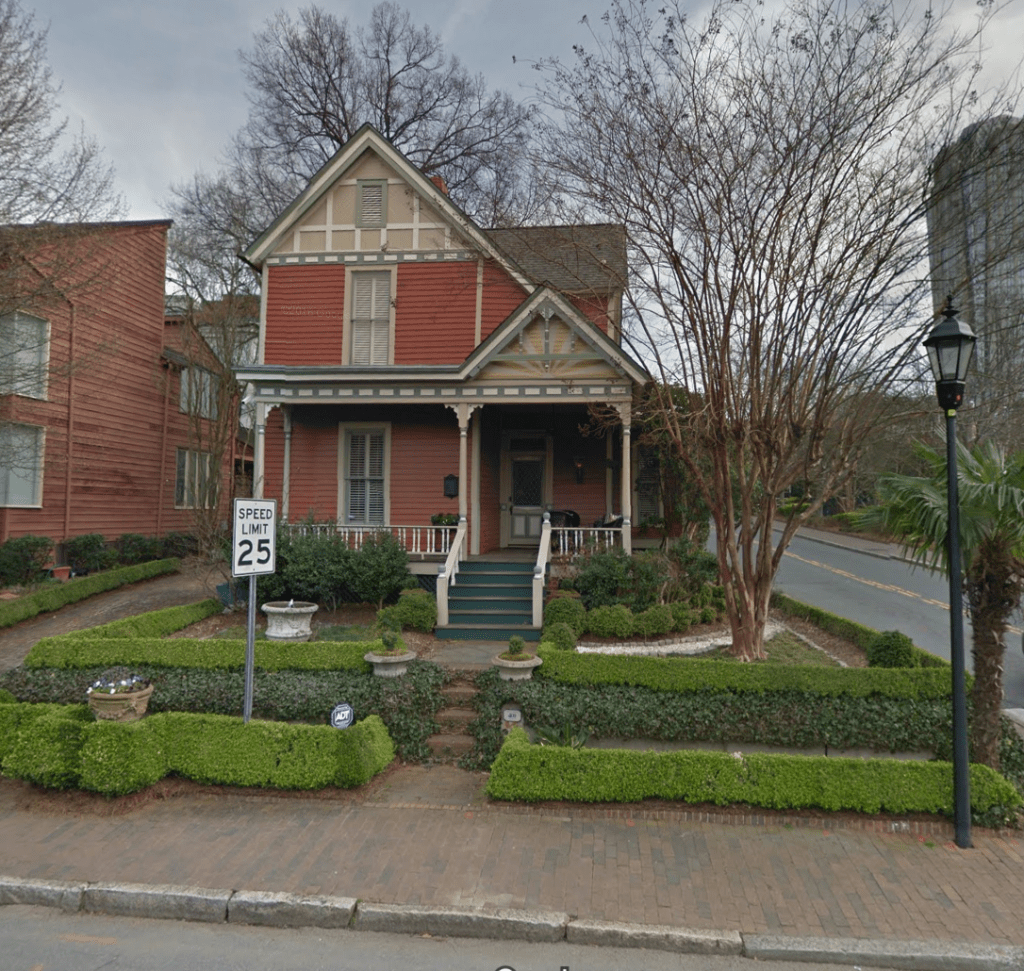

Come down to Winston-Salem, North Carolina and visit Johnny, me, and our dog Yogi. Soon the museum anarchist will soon be in the house! In a case of life imitating art, we will be living in an actual historic property called The Fourth House (c. 1767), which is, in fact, the oldest house in Winston-Salem… and keep an eye on what develops at Old Salem Museums & Gardens – they’ve hired me, the Museum Anarchist, as President & CEO. And by hiring me, they have made it 100% clear, they mean business. Even though our first home stood right in the middle of a densely populated urban area of Charlotte, North Carolina, it felt like homesteading. We were a young, white couple of privilege with two small children and a dog, moving into an older, historically significant residential area long before I was mature enough to understand that “gentrification” was considered economic disaster to existing residents. At the time, I naively thought we were part of a grass-roots effort to fix up decaying sections of the city, bringing renewed interest and value to mislabeled historical neighborhoods. I had no notion of the effects our movement into the area might have on the pre-existing populations. I regret not being more sensitive to the effects of our movement into the area and how are neighbors felt. As I return now, some 20+ years later, the street is hardly recognizable, and all of those long-established neighbors have moved away.

Even though our first home stood right in the middle of a densely populated urban area of Charlotte, North Carolina, it felt like homesteading. We were a young, white couple of privilege with two small children and a dog, moving into an older, historically significant residential area long before I was mature enough to understand that “gentrification” was considered economic disaster to existing residents. At the time, I naively thought we were part of a grass-roots effort to fix up decaying sections of the city, bringing renewed interest and value to mislabeled historical neighborhoods. I had no notion of the effects our movement into the area might have on the pre-existing populations. I regret not being more sensitive to the effects of our movement into the area and how are neighbors felt. As I return now, some 20+ years later, the street is hardly recognizable, and all of those long-established neighbors have moved away.

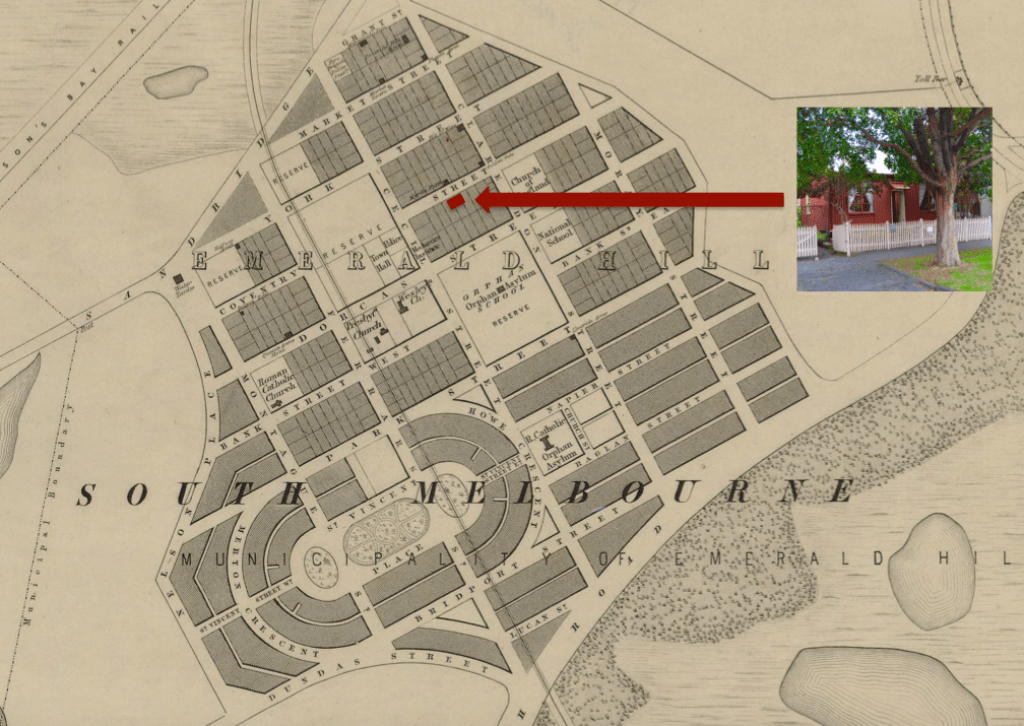

Everything on the street had a similar scale and was densely landscaped. After a moment, I located the Iron Houses hidden behind a large tree and densely landscaped front yard, all tucked behind a tidy white picket fence. I was struck by the feeling that it felt in scale and presence almost exactly like our first tiny home in Charlotte. I wondered if it was simply natural, when existing in a tiny house, to expand its presence and livability by integrating well-formed landscape “rooms” into the very structure of the home?

Everything on the street had a similar scale and was densely landscaped. After a moment, I located the Iron Houses hidden behind a large tree and densely landscaped front yard, all tucked behind a tidy white picket fence. I was struck by the feeling that it felt in scale and presence almost exactly like our first tiny home in Charlotte. I wondered if it was simply natural, when existing in a tiny house, to expand its presence and livability by integrating well-formed landscape “rooms” into the very structure of the home?

Once my items were secured, I walked backward down the stairs and began exploring. To my surprise, there was not simply one pre-manufactured iron house on the site, but three. Each was in varying degrees of restoration. The organization of these three houses produced a friendly landscaped, cloistered area. The main iron house, The Patterson House (c. 1850), the one in which I was spending my overnight, was original to the site. The second dwelling, The Abercrombie House, was moved in 1970, placed on the back edge of the property, and left as they found it. This unrestored iron house has the evocative quality of a stabilized ruin. The third iron house, The Bellhouse (c. 1853), serves as the education center. It had been stripped down to the fundamental structure to show how these pre-fabricated dwellings were made. Combined, all three of the structures tell a nicely tied narrative.

Once my items were secured, I walked backward down the stairs and began exploring. To my surprise, there was not simply one pre-manufactured iron house on the site, but three. Each was in varying degrees of restoration. The organization of these three houses produced a friendly landscaped, cloistered area. The main iron house, The Patterson House (c. 1850), the one in which I was spending my overnight, was original to the site. The second dwelling, The Abercrombie House, was moved in 1970, placed on the back edge of the property, and left as they found it. This unrestored iron house has the evocative quality of a stabilized ruin. The third iron house, The Bellhouse (c. 1853), serves as the education center. It had been stripped down to the fundamental structure to show how these pre-fabricated dwellings were made. Combined, all three of the structures tell a nicely tied narrative.

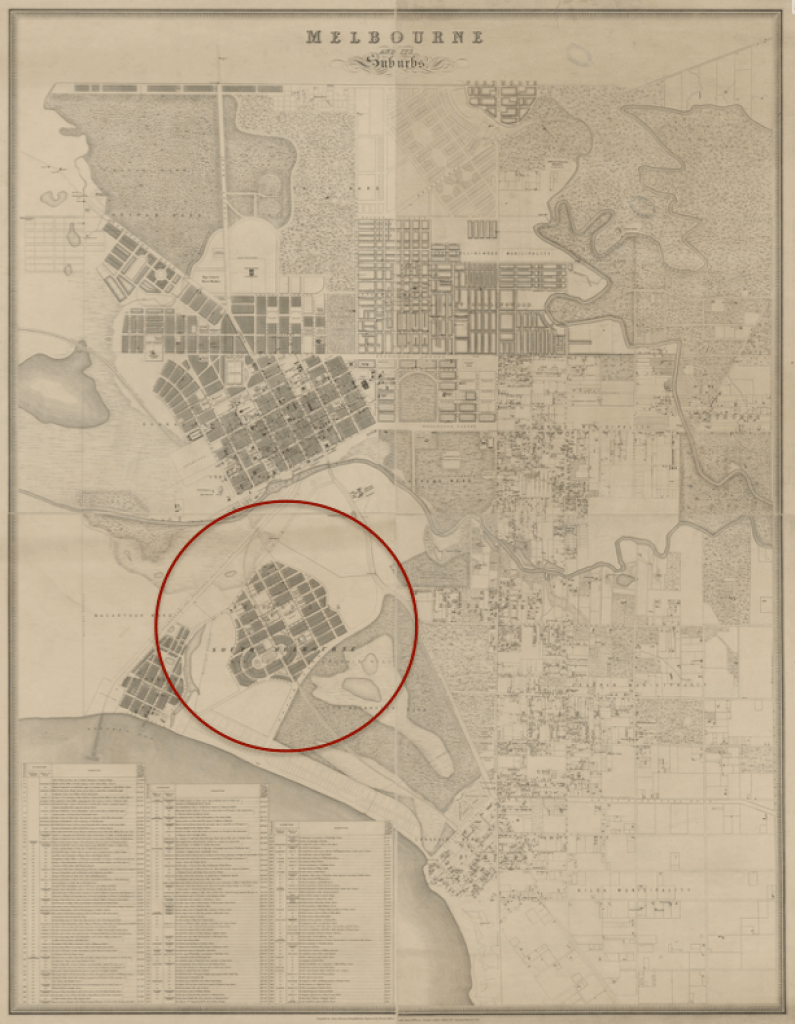

Since I did not know much of the history of the people who originally occupied the land where Melbourne now rests, my host provided information that helped inform my experience. Melbourne lies within the traditional lands of the Yalukit Willamm people, who inhabited the swampy areas below Emerald Hill (South Melbourne). The various clans comprising this group met in large gatherings on land now occupied by Melbourne. Although white settlement of Victoria did not commence until the 1830s, earlier accounts of indigenous people by settlers described them as “peaceable natives”. Unfortunately, early on, there are written accounts of Aboriginal women from these clans being kidnapped and used as laborers and concubines. These kidnappings often resulted in hostile battles and relationships between Aboriginal people and European invaders.

Since I did not know much of the history of the people who originally occupied the land where Melbourne now rests, my host provided information that helped inform my experience. Melbourne lies within the traditional lands of the Yalukit Willamm people, who inhabited the swampy areas below Emerald Hill (South Melbourne). The various clans comprising this group met in large gatherings on land now occupied by Melbourne. Although white settlement of Victoria did not commence until the 1830s, earlier accounts of indigenous people by settlers described them as “peaceable natives”. Unfortunately, early on, there are written accounts of Aboriginal women from these clans being kidnapped and used as laborers and concubines. These kidnappings often resulted in hostile battles and relationships between Aboriginal people and European invaders.

As we all stood in the cloister, amidst the three iron “portables”, I couldn’t help but imagine how an Aboriginal person of the time might have viewed these dwellings. Permanent, made out of a locally unknown material, arranged in a hyper-organized fashion, these houses in South Melbourne must have seemed like the equivalent of warships floating in the sea of territory lands.

As we all stood in the cloister, amidst the three iron “portables”, I couldn’t help but imagine how an Aboriginal person of the time might have viewed these dwellings. Permanent, made out of a locally unknown material, arranged in a hyper-organized fashion, these houses in South Melbourne must have seemed like the equivalent of warships floating in the sea of territory lands. Watching the dinner cook on the open fire, we chatted about Aboriginal people, Australian colonization, the gold rush era in Melbourne, and my other “One-Night Stands”. Hovering above the open fire pit was a beautiful Australian sunset. Its brilliant colors seemed to stand firmly against the hard-edged corrugated steel roof of the iron houses. There was a moment when the site became an intense post-modern, saturated landscape. As if to push through all of the history of the site, the spiritual power of the Australian sun, land and essence seemed to coalescence into a dream-like story of simultaneous voices – the Aboriginal, the colonizers, all the way unto us – standing by the fire watching the sparks fly upward into the purple/pink sky. Even in the middle of Melbourne, you could hear the voice of the land reach out.

Watching the dinner cook on the open fire, we chatted about Aboriginal people, Australian colonization, the gold rush era in Melbourne, and my other “One-Night Stands”. Hovering above the open fire pit was a beautiful Australian sunset. Its brilliant colors seemed to stand firmly against the hard-edged corrugated steel roof of the iron houses. There was a moment when the site became an intense post-modern, saturated landscape. As if to push through all of the history of the site, the spiritual power of the Australian sun, land and essence seemed to coalescence into a dream-like story of simultaneous voices – the Aboriginal, the colonizers, all the way unto us – standing by the fire watching the sparks fly upward into the purple/pink sky. Even in the middle of Melbourne, you could hear the voice of the land reach out.

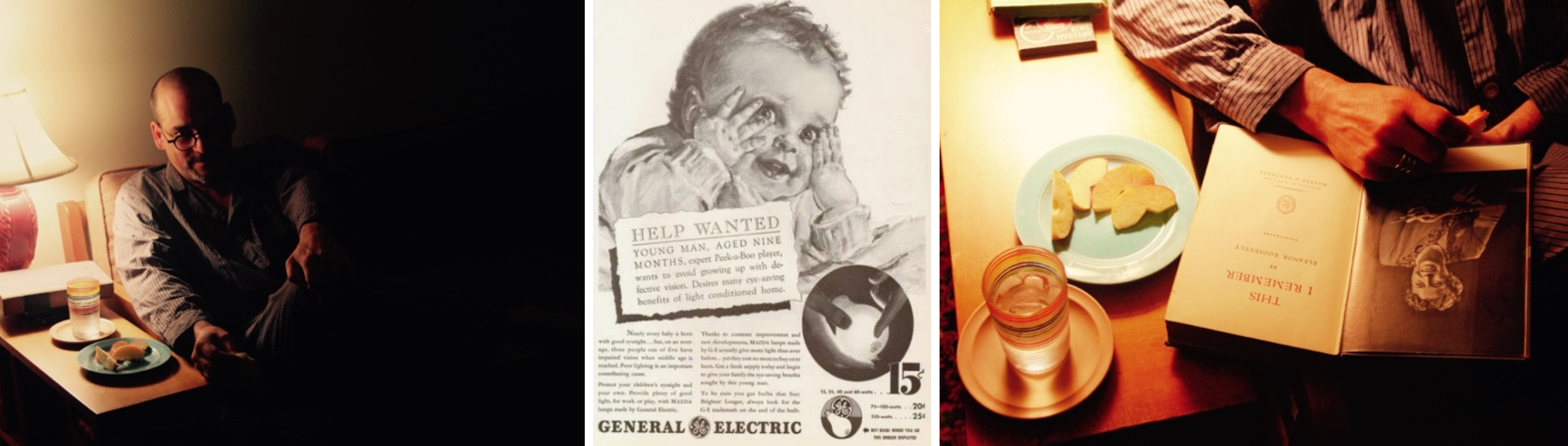

As I stepped closer to Wharton’s colorful, cubist, expressionist jewelry box–it looked beautiful, yet clearly used. The compositions were at the same time powerful, yet harsh, and discordant. The house wasn’t painted, it occupied Color, and as an area was used, the top color was eroded away and a lower color revealed itself. This wasn’t by accident – it appeared fully intentional. I immediately thought of Rudolph Steiner’s paintings and of his philosophy of how color, painting, and the arts could affect society as a whole. He believed in the healing qualities of color, the nature of this color “therapy” being to stimulate different emotional responses for each individual. Most discuss the studio as “colorful” and “playful”. I, however, see it as a search for direction – an acknowledgment of our lives as foggy, beautiful, and at times confusing.

As I stepped closer to Wharton’s colorful, cubist, expressionist jewelry box–it looked beautiful, yet clearly used. The compositions were at the same time powerful, yet harsh, and discordant. The house wasn’t painted, it occupied Color, and as an area was used, the top color was eroded away and a lower color revealed itself. This wasn’t by accident – it appeared fully intentional. I immediately thought of Rudolph Steiner’s paintings and of his philosophy of how color, painting, and the arts could affect society as a whole. He believed in the healing qualities of color, the nature of this color “therapy” being to stimulate different emotional responses for each individual. Most discuss the studio as “colorful” and “playful”. I, however, see it as a search for direction – an acknowledgment of our lives as foggy, beautiful, and at times confusing.