GETTING TO PASAQUAN

You don’t just happen upon Pasaquan Estate, the built environment created by the visionary St. E.O.M. You really have to make a committed effort to get in a car and drive through the two-lane backroads of rural Georgia to find it. I knew that Georgia consisted of miles and miles of pine barrens, and I, mistakenly, imagined them as quiet forests of tall pine trees, gently blowing in the breeze while growing out of a floor of soft, welcoming brown pine needles. Instead, while driving along the isolated road, I saw jagged loblolly pines in a dense and choppy landscape that looked, as I then surmised it felt, prickly and adversarial. This desolate area of Georgia has a history of being a land of escape, seclusion, and dissent. During the American Civil War, the pine barrens were a destination for wartime deserters and those trying to avoid the destruction of war. I wondered what imagination must have been able to see this inhospitable landscape and envision a dreamscape. I sensed that this One Night Stand at Pasaquan would be unlike any others I had experienced.

The landscape in February 2020 was composed mainly of browns and grays. The weather was typical of a mild Georgia winter, and the green of the tall pines penetrated the blue sky, making the vista appear like the skyline of a dense city whose chimneys and church steeples floated above the mass of buildings below. It was impossible to gain a long view as I stared into the pine forests. In fact, the lower levels were almost dusky because of the lack of light, giving the entire forest the appearance of a matted coat of hair on a dog. In areas, I could see vast acreage that had been selectively scorched. The remaining landscape resembled the outline of a city that had been through a war. Occasional burnt pine trees with no needles poked up through an undercover of completely charred shrubs and saplings. I later learned that state and local governments often facilitate this type of controlled fire-induced underbrush clearing because it is the only way to protect pine barrens from unexpected vast forest fires. Although controlled burns bring about new growth, thus making the pine barrens attract and maintain wildlife and plant species, the initial results are a blackened, desolate landscape. As the Dadaist artist Picabia suggested, the only way to save something precious is seemingly to destroy it – transform it. In a way, one must re-make it into something else. Remember that.

DESTINATION

DESTINATION

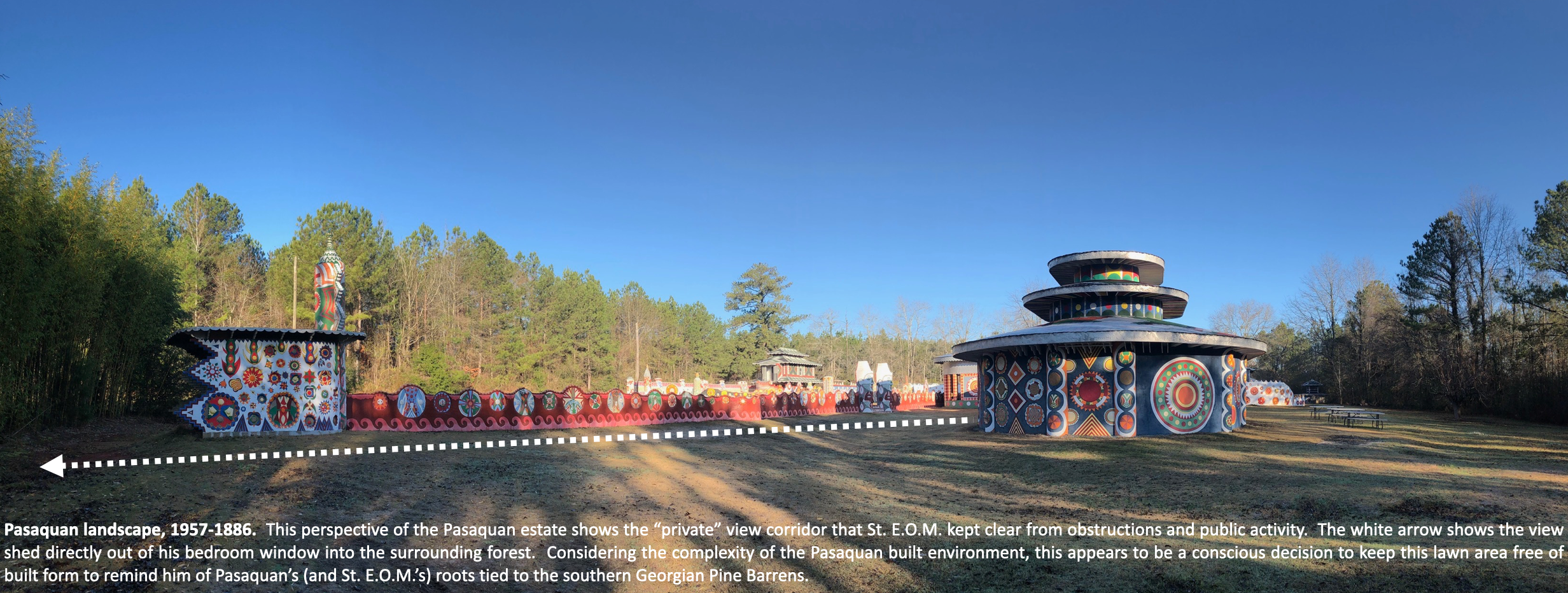

This bleak landscape is part of the compound that was once home to St. E.O.M, originally named Eddie Owen Martin (1908-1986). He was the charismatic visionary who designed and built the singular Pasaquan Estate. The crafting of his unique compound did not begin until 1957 when, after decades of travel, sex work, illegal activities, fortune-telling, underground life in NYC, and brief prison stints, St. E.O.M. left NYC and moved permanently to a Georgia farmhouse on four acres he had inherited from his mother. He started building the walls of the estate in 1957 and continued the site’s creation up until his death in 1986. In its final form Pasaquan emerged as a 19-room expansive organism consisting of open-air and enclosed spaces. Much like a traditional rural Georgia farm with barns, outbuildings, and fenced off pastureland and crops, the built landscape of Pasaquan consists of outbuildings and fences, but instead of functioning as farm spaces, they are walls and platforms that define multiple theatrical stages, honorific stairways, processional pylon gateways, remote meditation studios, and a caretaker’s house.

Pasaquan was used by St. E.O.M. as the center of his fortune-telling business. So well-known was his ability to tell the future that he often had multiple cars parked beyond his front yard, with drivers and passengers waiting their turn to get their fortunes told. Visitors arrived unannounced, wanting to experience not only St. E.O.M. himself, but also the mystical grounds of the estate. In forming his own spiritual idea of “Pasaquoyanism,” St. E.O.M. combined a wide mixture of religious concepts and philosophies with aesthetic principles from across the world. Separate from the site standing out as one of the most complete visionary landscapes in the United States, it, like a fortune teller, asks many more questions than it answers.

Pasaquan was used by St. E.O.M. as the center of his fortune-telling business. So well-known was his ability to tell the future that he often had multiple cars parked beyond his front yard, with drivers and passengers waiting their turn to get their fortunes told. Visitors arrived unannounced, wanting to experience not only St. E.O.M. himself, but also the mystical grounds of the estate. In forming his own spiritual idea of “Pasaquoyanism,” St. E.O.M. combined a wide mixture of religious concepts and philosophies with aesthetic principles from across the world. Separate from the site standing out as one of the most complete visionary landscapes in the United States, it, like a fortune teller, asks many more questions than it answers.

ARRIVAL

This landscape of endless pine trees made my arrival at St. E.O.M.’s Pasaquan all the more impactful. After meandering down multiple miles of lonesome two-way roads, I suddenly came upon a vibrant, graphic sign. With the exception of the new colorful sign and the high chain-link fence surrounding the complex, the entrance road has changed very little since St. E.O.M. lived at Pasaquan. It is still unpaved and framed by the pine barrens. As I turned into the unpaved road, the tight vista of the pine forest opened up to a wide clearing. In the middle of the clearing was a vividly present and intentful landscape. I can only describe it as shocking. I had seen photos of the complex, but I assumed the photographers had used strong, highly saturated Instagram filters to produce the bright colors. No, those intense pictures were accurate.

Entering more fully into the clearing, I spotted the main landscape standing boldly to my right. What I saw was a farmhouse peeking through the accretions of a vast, interconnected exterior wall system. Bright colors, faces, mandala, genitalia, and shapes of all types sang and danced in a constant opera of storytelling. My questions began as soon as I opened the door of the car, and they are still with me today as I sit in my little office and write this. The colorful orgy of built form rebelliously mocked the pine barrens that surrounded it. The dull green and brown trees of the shadowy backdrop seemed to withdraw, like homely spectators at a dance, and understand that they were in the presence of an impenetrable avant-guard spectacle.

Entering more fully into the clearing, I spotted the main landscape standing boldly to my right. What I saw was a farmhouse peeking through the accretions of a vast, interconnected exterior wall system. Bright colors, faces, mandala, genitalia, and shapes of all types sang and danced in a constant opera of storytelling. My questions began as soon as I opened the door of the car, and they are still with me today as I sit in my little office and write this. The colorful orgy of built form rebelliously mocked the pine barrens that surrounded it. The dull green and brown trees of the shadowy backdrop seemed to withdraw, like homely spectators at a dance, and understand that they were in the presence of an impenetrable avant-guard spectacle.

There was no mistaking where to park and where the front entrance was located. Everything about the built landscape led me to the massive androgynous spiritual guardians of the complex. These pillars are decorated with two-dimensional imagery of beaded, tattooed warriors wearing headdresses that culminated in a fiery flame poking towards the sky. Often confronted with large numbers of unscheduled visitors, St E.O.M. himself placed signs by this front entrance giving visitors clear instructions on what was expected of them: “Beware of bad dogs. Please blow horn and stay in car until I come out” or “Blow horn….” After a bit of a wait, visitors would be met by St. E.O.M. standing between these pillars, greeting them in one of his colorful bespoke garments and beads, with hands in prayer. St. E.O.M. clearly understood the importance of an impactful arrival, the symbolic strength of initial impressions, and the power of keeping people guessing.

There was no mistaking where to park and where the front entrance was located. Everything about the built landscape led me to the massive androgynous spiritual guardians of the complex. These pillars are decorated with two-dimensional imagery of beaded, tattooed warriors wearing headdresses that culminated in a fiery flame poking towards the sky. Often confronted with large numbers of unscheduled visitors, St E.O.M. himself placed signs by this front entrance giving visitors clear instructions on what was expected of them: “Beware of bad dogs. Please blow horn and stay in car until I come out” or “Blow horn….” After a bit of a wait, visitors would be met by St. E.O.M. standing between these pillars, greeting them in one of his colorful bespoke garments and beads, with hands in prayer. St. E.O.M. clearly understood the importance of an impactful arrival, the symbolic strength of initial impressions, and the power of keeping people guessing.

The site was exactly as I had expected and not at all what I imagined. I was greeted at the gate by Pasaquan’s Caretaker, Charles Fowler, who was appropriately accessorized with a St. E.O.M. beaded necklace and bright red-frame glasses. Quiet and thoughtful, Charles started to walk me around and give me the background of the site. We explored and walked from garden room to garden room. Each space seemed to have a different set of symbolic definitions and boundaries – oddly discordant but still related. I had numerous questions; I won’t lie. I wanted to understand the site, and initially I wasn’t having an easy time of it. The more answers I got from Charles, the deeper the riddles became. Things were only getting “curiouser and curiouser.” I asked to see a site plan, in hopes that I could better understand the bones of Pasaquan. No such luck.

The site was exactly as I had expected and not at all what I imagined. I was greeted at the gate by Pasaquan’s Caretaker, Charles Fowler, who was appropriately accessorized with a St. E.O.M. beaded necklace and bright red-frame glasses. Quiet and thoughtful, Charles started to walk me around and give me the background of the site. We explored and walked from garden room to garden room. Each space seemed to have a different set of symbolic definitions and boundaries – oddly discordant but still related. I had numerous questions; I won’t lie. I wanted to understand the site, and initially I wasn’t having an easy time of it. The more answers I got from Charles, the deeper the riddles became. Things were only getting “curiouser and curiouser.” I asked to see a site plan, in hopes that I could better understand the bones of Pasaquan. No such luck.

Since I was here for a One Night Stand overnight stay, I decided to unpack my bags in the visitor greeting room. There were two daybeds that visitors had once sat upon while they spoke to St. E.O.M. and heard him tell their fortunes. Occasionally these beds would be the place visitors slept. I changed into more comfortable clothes and started to walk around the oozing house. As I roamed, I finally began to find some answers.

Since I was here for a One Night Stand overnight stay, I decided to unpack my bags in the visitor greeting room. There were two daybeds that visitors had once sat upon while they spoke to St. E.O.M. and heard him tell their fortunes. Occasionally these beds would be the place visitors slept. I changed into more comfortable clothes and started to walk around the oozing house. As I roamed, I finally began to find some answers.

THE MAIN HOUSE

The main house at Pasaquan had very ordinary beginnings. Originally the landscape held only a small, typical four-room Southern farmhouse (c. 1885) with a large open porch and central fireplace. It had a shed addition at the back comprised of two small rooms bisected by an open-air passthrough. Both the house morphology and the evolution of the rear shed addition correspond to other 19th-century Georgia farmhouse designs (see examples below). In fact, although greatly modified, today the now yellow house is clearly visible as the seminal generator of the built landscape surrounding it.

St E.O.M.’s mother secretly saved money for years so that she could buy the house and 100-acre property. It represented freedom and protection–freedom from her life as a housewife and protection from an abusive husband. The core of this little house served as the emotional, architectural, and germinating cocoon for the Pasaquan one sees today. I tried to imagine the mind that could see the simple farmhouse and create a landscape swirling around it of such different character and personality. The original house and the site today seem not from the same world. The “Re-garmenting” of this little farmhouse into Pasaquan could have been facilitated only by someone who understood deeply and personally how exteriors may not always reflect the true essence of identity. The true meaning of our existence can be found through honoring the power of that which is not seen. Beyond merely eccentric, St E.O.M. was in constant motion, questioning the solidity, accuracy, validity, and genitalia of all that he experienced and was told to be true. This is Pasaquan.

St E.O.M.’s mother secretly saved money for years so that she could buy the house and 100-acre property. It represented freedom and protection–freedom from her life as a housewife and protection from an abusive husband. The core of this little house served as the emotional, architectural, and germinating cocoon for the Pasaquan one sees today. I tried to imagine the mind that could see the simple farmhouse and create a landscape swirling around it of such different character and personality. The original house and the site today seem not from the same world. The “Re-garmenting” of this little farmhouse into Pasaquan could have been facilitated only by someone who understood deeply and personally how exteriors may not always reflect the true essence of identity. The true meaning of our existence can be found through honoring the power of that which is not seen. Beyond merely eccentric, St E.O.M. was in constant motion, questioning the solidity, accuracy, validity, and genitalia of all that he experienced and was told to be true. This is Pasaquan.

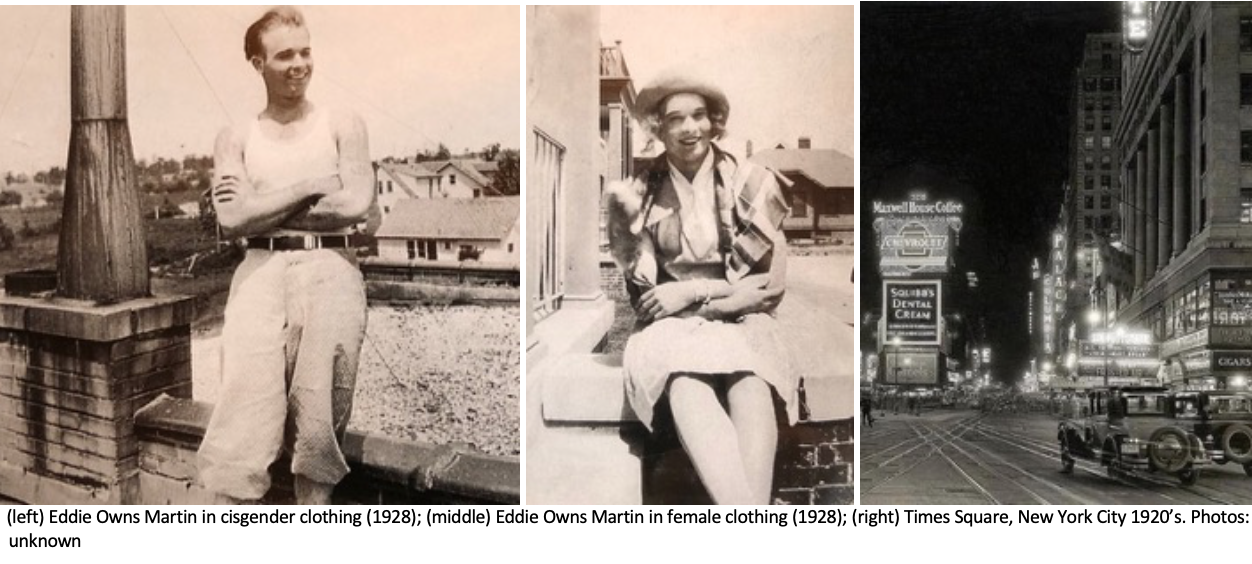

THE EDUCATION OF EDDIE

Like many of us, St. E.O.M. spent his 20’s experimenting and searching for himself, attempting to contextualize himself within the world. Running away from his abusive father and rural Georgia lifestyle, he eventually moved to New York City in 1923 as a teenager and lived the life of a street hustler, drag queen/cross dresser, illicit gambler, and enthusiastic frequenter of a myriad of nightclubs. The complexity of this life in NYC was explained by St. E.O.M. himself,

“For a while after I got to New York I was confused in my mind ‘bout whether I should be on the gay side or on the other side, and I had that complex about this manliness stuff they try to lay on you in this society….But I got over those complexes later, when I decided it was really just a matter of getting’ experience and knowin’ people and knowin’ things.”

SEX, HUSTLING, CRUISING, AND DRAG

Between 1923 and 1957 St. E.O.M lived intermittently in New York City. During this time he jumped from apartment to apartment. Many times his location was determined by a lover or a pick-up’s kindness. Some of the time, starting in the early 1940’s, he lived on West 52nd Street (aka Hell’s Kitchen), above the jazz club The Famous Door. From his home he could hear Count Basie “swingin’” all night. This area of NYC was considered the heart of jazz and nightlife. During the 1930s and 1940s, West 52nd Street was called “Swing Street.” It began as a series of speakeasies and then jazz clubs, which eventually gave way to burlesque houses. At its height the area held sixteen jazz clubs in two blocks. The West Side in the 1950’s was still full of shipping yards and docks with warehouses and commercial establishments mixed with residential upstairs. And all of this was only a few blocks from Times Square. Clearly, St. E.O.M.’s life education was occurring in a classroom of complexity, vibrancy, sound, dance, and crowds. His world consisted of high art, base sexual desire, and capitalism joined onto one messy sidewalk.

Between 1923 and 1957 St. E.O.M lived intermittently in New York City. During this time he jumped from apartment to apartment. Many times his location was determined by a lover or a pick-up’s kindness. Some of the time, starting in the early 1940’s, he lived on West 52nd Street (aka Hell’s Kitchen), above the jazz club The Famous Door. From his home he could hear Count Basie “swingin’” all night. This area of NYC was considered the heart of jazz and nightlife. During the 1930s and 1940s, West 52nd Street was called “Swing Street.” It began as a series of speakeasies and then jazz clubs, which eventually gave way to burlesque houses. At its height the area held sixteen jazz clubs in two blocks. The West Side in the 1950’s was still full of shipping yards and docks with warehouses and commercial establishments mixed with residential upstairs. And all of this was only a few blocks from Times Square. Clearly, St. E.O.M.’s life education was occurring in a classroom of complexity, vibrancy, sound, dance, and crowds. His world consisted of high art, base sexual desire, and capitalism joined onto one messy sidewalk.

The early period of St. E.O.M’s life in NYC is a period later described as the “Pansy Craze.” Pockets of the city like Greenwich Village, Times Square, Union Square, and Harlem contained nightclubs, theaters, drag shows, drag balls, and gay street hustlers. This was the world within which St. E.O.M. matured. I can only imagine how this atmosphere helped shape his aesthetic and environmental view. His was a world of theatrics and unbounded possibility. The boundaries of sexuality and gender became fluid, and the manifestation of these ideas in the physical material world could be altered to present whatever image he desired. The original quality of a situation did not dictate the end result. Either for survival or as playful possibility, the power of imagination could re-define any situation.

So formative was this period in St. E.O.M.’s life, that once he returned to his mother’s farm in 1957 and began creating his masterpiece, he designated a wall of honor to it at Pasaquan. Placed directly in the entrance courtyard for everyone to see, he crafted hand-drawn, incised portraits of “Drag Queen Warriors.” Each face was dedicated to a particular friend from his time as a hustler and drag queen in NYC. This powerful tribute illustrates a past life full of androgynous, multi-ethnic, bejeweled identities – gallantly defending a world of choice against a culture of suppression and absolutes. One can imagine the crafted, layered meanings and costuming that sliced through, segmented, and re-defined this world of alleyway sex, peep shows, pageants, and balls. I suspect that if we begin to look at Pasaquan as an extension of NYC’s 1920-1930’s drag and jazz culture, filled with gender-bending, honorific pageantry, voluptuous clothing, sensuous interpretive jazz, and flamboyant theatrics, we can see how Pasaquan fits clearly within this microcosm of counter-normative, sexually fluid urbanity. He simply brought it all back to the pine barrens of rural Georgia.

So formative was this period in St. E.O.M.’s life, that once he returned to his mother’s farm in 1957 and began creating his masterpiece, he designated a wall of honor to it at Pasaquan. Placed directly in the entrance courtyard for everyone to see, he crafted hand-drawn, incised portraits of “Drag Queen Warriors.” Each face was dedicated to a particular friend from his time as a hustler and drag queen in NYC. This powerful tribute illustrates a past life full of androgynous, multi-ethnic, bejeweled identities – gallantly defending a world of choice against a culture of suppression and absolutes. One can imagine the crafted, layered meanings and costuming that sliced through, segmented, and re-defined this world of alleyway sex, peep shows, pageants, and balls. I suspect that if we begin to look at Pasaquan as an extension of NYC’s 1920-1930’s drag and jazz culture, filled with gender-bending, honorific pageantry, voluptuous clothing, sensuous interpretive jazz, and flamboyant theatrics, we can see how Pasaquan fits clearly within this microcosm of counter-normative, sexually fluid urbanity. He simply brought it all back to the pine barrens of rural Georgia.

GENITALIA

When I was walking through the Pasaquoyan landscape, the built form and imagery were repeatedly asking me questions. It feels as if the literalness of the physical world is playing a trick on you by recombining in such a way to produce another message entirely. The domestic environment looks like things you know and understand–a fence, a house, a door–yet how they are combined, resurfaced, colored, and shaped is askew and inverted. Similarity flows into differences, which then flow into the unique. Recurring themes thread throughout the landscape and house.

One of the most asked questions at Pasaquan has to do with gender and its relationship to genitalia. Myriads of penises are depicted in the Pasaquan built environment. They are of all sizes and shapes. The human forms from which the penises extend seem more like background noise. Each is decorated individually with varying colors and shapes that extend into the surrounding circle mandala medallions and eventually become part of the larger Pasaquan wall system and overall landscape. At times they alternate between female bodies and genitalia, as if to say the sexes are interchangeable – or possibly that they don’t matter at all – or yet, on the other hand, may be the most important thing above all else.

Long before “gender fluidity” was acknowledged, and on the heels of the widely read Kinsey Reports, (Sexual Behavior in the Human Male [1948] and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female [1953]), St. E.O.M. seemed to be manifesting the very concept of sexual fluidity in built form. In interviews he makes it clear that in his hustling days, he could just as easily have had sex with a woman as with a man, as long as he was aroused by the individual. He seems to have held a very sex-positive approach to intimate relationships. It is interesting to note that a large portion of Kinsey’s subjects were pulled from the Times Square area of NYC, and it is not unreasonable to imagine St. E.O.M. as a part of that experimental study population.

Long before “gender fluidity” was acknowledged, and on the heels of the widely read Kinsey Reports, (Sexual Behavior in the Human Male [1948] and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female [1953]), St. E.O.M. seemed to be manifesting the very concept of sexual fluidity in built form. In interviews he makes it clear that in his hustling days, he could just as easily have had sex with a woman as with a man, as long as he was aroused by the individual. He seems to have held a very sex-positive approach to intimate relationships. It is interesting to note that a large portion of Kinsey’s subjects were pulled from the Times Square area of NYC, and it is not unreasonable to imagine St. E.O.M. as a part of that experimental study population.

In St. E.O.M.’s early NYC hustling days, sex was a commodity. There was no moral judgment placed on the act. Time was money, and he attributed his psychic ability, in part, to being able to assess men he would see on the streets: “ I was always lookin’ for eyes, to search people out that wanted me…But I would know they was out for somethin’. I could tell by the way they looked at me. That’s when I started learnin’ to be psychic.”

After viewing Pasaquan initially, I found myself standing in front of a large site plan of the Kohler-facilitated restoration work that took place at Pasaquan. I kept blinking my eyes, re-focusing, and then walked farther away from the drawing. To my eyes, St. E.O.M. didn’t just decorate Pasaquan with sculptures of penises – Pasaquan was a penis. In fact, in speaking to friends who often visited Pasaquan during St. E.O.M.’s lifetime, I learned that the front drive entranceway meadow was often, with the use of a lawn mower, shaped into the form of a large penis. The road that visitors arrived upon, unknown to the guests, morphed right into the penis shape. The tall grass meadow surrounding the mown phallus disguised the symbolic gesture. In hindsight, one friend jokingly noted that St. E.O.M.’s audience for this phallic landscape, instead of being actual visitors seeking fortune telling, might have been all the military men flying in and out of Fort Benning looking down from the sky. Today, in studying at the site plan and subsequently walking around, I envisioned how many of the outbuildings resemble the interaction of egg and sperm. The shape of the built environment evolved from that inherited simple farmhouse into a large multi- penis-shaped complex. St. E.O.M. was experimenting with gender fluid, sexual macro-symbolism.

After viewing Pasaquan initially, I found myself standing in front of a large site plan of the Kohler-facilitated restoration work that took place at Pasaquan. I kept blinking my eyes, re-focusing, and then walked farther away from the drawing. To my eyes, St. E.O.M. didn’t just decorate Pasaquan with sculptures of penises – Pasaquan was a penis. In fact, in speaking to friends who often visited Pasaquan during St. E.O.M.’s lifetime, I learned that the front drive entranceway meadow was often, with the use of a lawn mower, shaped into the form of a large penis. The road that visitors arrived upon, unknown to the guests, morphed right into the penis shape. The tall grass meadow surrounding the mown phallus disguised the symbolic gesture. In hindsight, one friend jokingly noted that St. E.O.M.’s audience for this phallic landscape, instead of being actual visitors seeking fortune telling, might have been all the military men flying in and out of Fort Benning looking down from the sky. Today, in studying at the site plan and subsequently walking around, I envisioned how many of the outbuildings resemble the interaction of egg and sperm. The shape of the built environment evolved from that inherited simple farmhouse into a large multi- penis-shaped complex. St. E.O.M. was experimenting with gender fluid, sexual macro-symbolism.

HAIR

In addition to phallic representation, one of the most noticeable physical features of the faces, pylons, and symbolic imagery of Pasaquan is hair and how it is illustrated. These forms show vertical, tall, pointed hairdos that draw the faces and bodies upward to the sky. St. E.O.M. describes the importance of hair and the forming of it as a fundamental aspect of his religious concept of Pasaquoyanism. From his study of ancient civilizations, St. E.O.M. deciphered that uncut hair held spiritual power. Hair could become a receptor for spiritual feelings and truth, if it was knotted, tied, and swept upward in a vertical manner. He describes an instance of particular importance:

So, I looked at the ancient art in museums, and I got holt of this book on Mayan art called the Kingsborough Edition, where some Englishman copied all these inscriptions and hieroglyphics. And in that book, it shows this God Quetzalcoatl sitten’ with his legs crossed and his hair all bound up, and this thing stickin’ out of it, and he’s got his finger pointin’ at his hair, like this. And when I saw that, I said to myself, “well that’s a message there It’s tellin’ you somethin’ ‘bout the hair…the hair up in these designs was just like lines of trees, ‘cause if you keep pullin’ ‘em up, they’ll stand up.”

The particular book he “got holt of” appears to be the 1830-1831 six-volume Antiquities of Mexico (a facsimile of an original Mexican painting is housed at the Royal Library at Dresden). Although there are many illustrations that could substantiate St. E.O.M.’s explanation of the origins of the Pasaquoyan up-hair symbolism, I was able to locate one that, conjecturally at least, seems to be the type of image that he describes.

This was the moment that I started to “get” Pasaquan. It was several things simultaneously. It was both a dwelling and a symbolic landscape. It was both a place to live everyday life, as well as a theatrical, sexually charged setting for a spiritual drag ball of one. The walls, genitalia, hair, and symbolism were created out of his need to transform the pine barrens of Georgia into Webster Hall of New York City. Genitalia, both male and female, as audience and spectators with faces and hair all centered on St. E.O.M.

THE HEART OF PASAQUAN

THE HEART OF PASAQUAN

One can easily get lost in the individual details of Pasaquan–such as the depiction and symbolism of genitalia or hair–but I wondered what, ultimately, was really the heart of Pasaquan? Of course, it was St. E.O.M. himself. But how did he define himself when no one else was there? When he didn’t have an audience or a fortune to tell? As I moved deeper into this One-night Stand, experiencing the house and landscape, I wondered what it was like for the man to live there. As I settled into the evening and made my bed, I found myself wondering where he had slept. In his most private moments, how did he define his inner world? I discovered that these questions could only be answered in the bathroom. More specifically, the answers were suggested by a basic, unadorned, white-painted wooden corner cabinet in the bathroom.

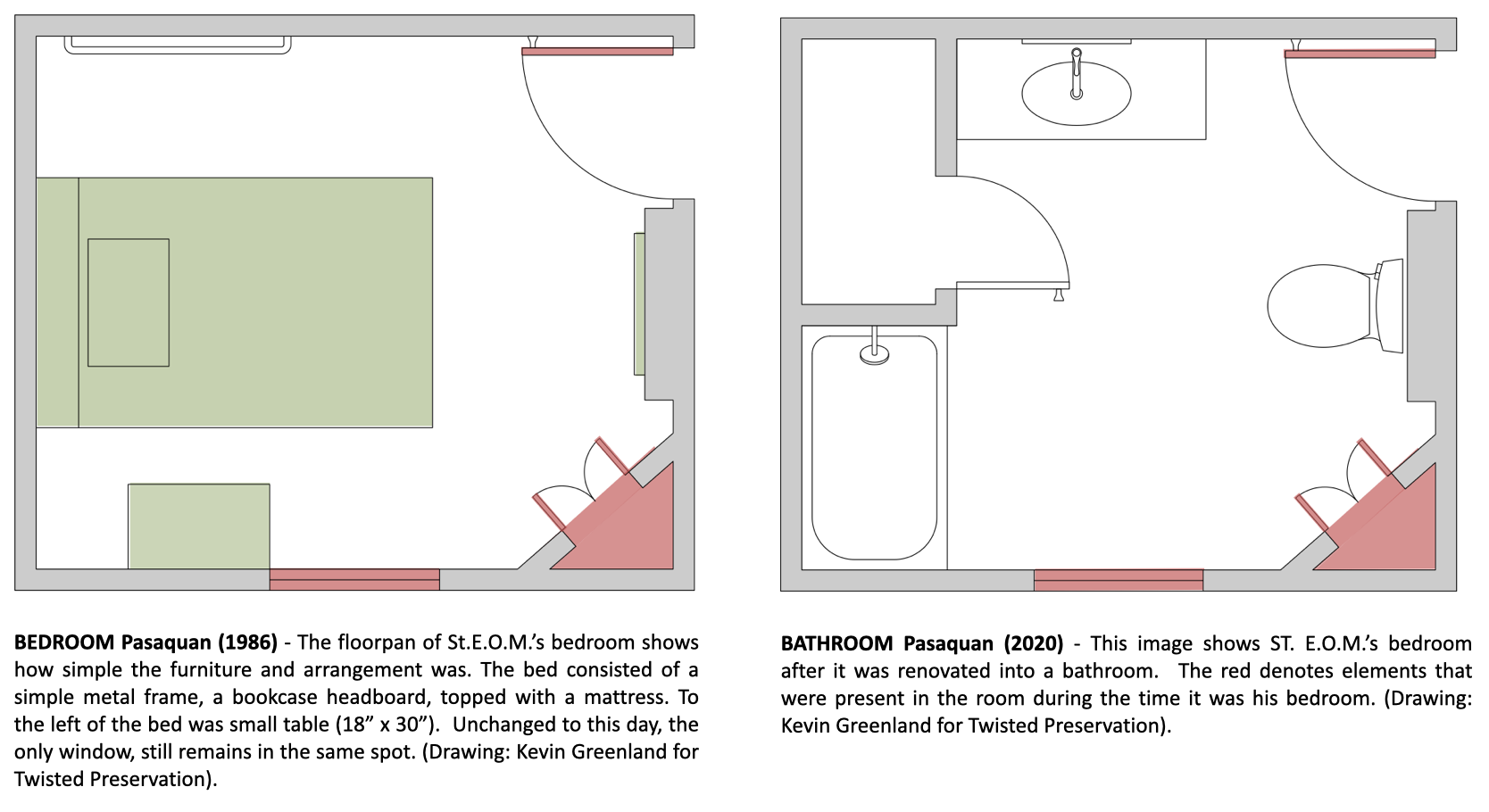

Throughout St. E.O.M.’s time living in NYC, he would regularly travel back to Georgia to assist his mother in harvesting the crops on the farm. According to an interview conducted with a St. E.O.M. family member, his bedroom always remained in the shed-roofed addition on the back of the farmhouse. Although he may have moved into different rooms within this shed addition, he resided in this section of the house throughout his life. Even after he moved back to Georgia permanently in 1955 after his mother died, he continued sleeping in the same space as he had done a decade before.

There are no photographs of his bedroom – he was very private about this room. Locating his long-term bedroom on a floor plan results in some startling revelations. His former bedroom has now been turned into the Pasaquan bathroom. It contains a toilet, shower, and sink within a space that before was empty of built-in appliances and furnishings, except for the small wooden cabinet in the southwest corner of the room.

Once, when exiting the shower in the room that had previously been St. E.O.M.’s bedroom, I noticed the nondescript corner cabinet and opened it. I optimistically thought that it would contain some meaningful relic display or important artifacts. It did not. It held basic bathroom articles such as toilet paper, hand towels, soap, etc. I wrongly assumed that its functional use connoted an immaterial existence. I closed the door and didn’t give the cabinet another thought. It wasn’t until later that I learned the bathroom was, in fact, St. E.O.M.’s bedroom for the entire time he lived at Pasaquan, and the cabinet was the only remaining element in the room from its time as his bedroom. The cabinet was the clue in helping me understand Pasaquan as a home, and it allowed me to more closely investigate the room that used to be St. E.O.M.’s bedroom.

The bedroom as St. E.O.M. occupied it was tiny, almost square. It had only one small window facing south with the built-in corner cabinet. The only decoration in the room was the window surround; it was painted with an abstract multi-colored design. The rest of the room was painted white and had a polished linoleum tile floor. Descriptions of the room’s furnishings during the time he lived there suggest an uncharacteristically sparse decoration scheme. The furniture arrangement was simple with the bed resting on an unobtrusive minimal metal floor frame with an attached bookcase headboard, and nearby stood a small rectangular side table. The corner cabinet I found in the bathroom existed much as it does today, serving as a spot for functional everyday items. Interviews suggest that the corner cabinet was filled with fabric and bedlinens – nothing unusual. Overall, the room’s almost monastic-like simplicity would have stood in stark contrast to the rest of colorful Pasaquan.

The white walls were bare except for one painting. The painting, produced during 1938 in his apartment on West 52nd St. while he was residing above the Famous Door Jazz Club, was a self-portrait of St. E.O.M. as a child walking down Main Street in his hometown of Glen Alta, Georgia. In the upper right is the country store and in the bottom left is the small train station. Eddie Owens Martin painted himself walking, detached and separated from everyone. He seems to skim through a small opening between the train station on one side and a moving horse-drawn wagon pulling a bale of cotton on the other. This painting represents a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The placement of the little boy, either symbolic or accidental, shows him at the center of a moving hub of activity. One direction would take him out of rural Georgia and perhaps to New York City and his activated life as a gay man. The other would most likely return him to his upbringing: back to the agricultural sharecropping life of his family. There he is, stationed in the center of this motion. It is almost as if he is documenting his moment of choice – should he stay in Georgia, or should he take the train to an unknown world outside of Glen Alta? Today we call this type of image a memory painting. In 1938, Eddie Owens Martin, then 30 years old, painted the image while living in New York City. He had already hopped the train to an expansive future – he was living the dream of that little boy walking down Main Street. The simple environment of the small-town contrasts with his new life of neon, celebratory Drag Balls and Jazz Clubs in New York City.

Just a few feet right of the corner cabinet is the only window in the bedroom. The singular decoration in the entire room exists on the window trim. It still exists today in the renovated bathroom. The trim is painted a red base color with hand-painted black undulating dual lines. The wood windowsill has been shaped and sculpted to reflect the same undulation as the painted trim. This window must have held a special place in St. E.O.M.’s mind.

From the bed looking through the window, the outside landscape was easily visible. The vista consisted of a long-range view across the grassy lawn into the forest. It was protected from the public’s gaze on one side by the sanctuary wing of the house itself and on the other side by a long, decorated barrier wall. A closer look at the site plan of Pasaquan reveals that St. E.O.M. was consciously careful not to infringe on this view, which included the shed out of his bedroom window. The walls of the sanctuary wing respectfully remain subservient to this private landscape space by pushing what should have been an architecturally centered massing off-center. The importance of this should not be minimized. It seems a clear design directive to maintain the original built form of the farmhouse bedroom window as an important symbolic fragment of St. E.O.M.’s past. What remained primary in the entire generative process of Pasaquan was a single, tiny window that was set into a wall enclosing a tiny room on a back-shed addition to a Georgia farmhouse.

I can imagine St. E.O.M. spending much of his time alone in his bedroom. He often spoke of having spiritual visions that directed his artistic production while sleeping alone in his bedroom. I see him either viewing the long vista out the small window, or instead, looking forward to the wall in front of him at the painting of his hometown showing the train station that took him out of Glen Alta. I sensed that the room allowed him to retreat within himself and exclude the outside world of visitors and fortune telling.

Could it be that everything which surrounded the simple bedroom was the protective layer that garmented St. E.O.M.’s internal world? All the landscape walls, theatrics, color, and symbolism served to keep people at a distance, both figuratively as well as literally. Surrounded by the painting of his hometown, and a single long vista reaching out into his past, this space must have felt the most emotionally raw of all of Pasaquan.

At the end of his life, he sat in the kitchen, wrote a letter to his friends, left it on the kitchen table, walked to his bedroom, and shut the door. Surrounded by his masterwork of Pasaquan, he chose part of the original farmhouse – his un-decorated, simple bedroom as the safest and most uncluttered spot in which to take his own life. Given the spare clarity of the room, St. EOM’s final thoughts could have been focused either on his painting or the view out the window. His letter left on the kitchen table explained, “Nobody is to blame but me and my past”.

Maybe these are the last questions St. E.O.M. was trying to share. What is the past? How does it shape our actions today – our choices? We just need to answer them for ourselves.

THE END

Pasaquan is the shiny object floating in a sea of brown and grey. On the one hand, the reason you are drawn to visit the site is its fabulousness: the color and eccentric environmental experiences that come from walking the many garden rooms and meditation sanctuaries. However, once that surface excitement settles, you can either go away, content with the other worldliness of the environment, or you can stick around and ask deeper questions and listen to the poetry. The truth is, if you stick around you get a bit melancholy – and you don’t know why exactly.

After a while, Pasaquan begins to feel like a sad memoir. It is the life story of a person who lived deeply, fully, made mistakes, and kept the results of that life accessorized by colorful paint, bespoke costumes, and resplendent, shiny metal tiles. Just like one of the warrior drag queens, Pasaquan is layered in make-up and sculpture in an onion-like expression of architecture, landscape walls, and spaces.

Ultimately, at the core of this complex, is a tiny undecorated room with one small window. When all the costumes were off, the visitors had left, and the fortune-telling was complete, St. E.O.M. retreated into the simplest of Pasaquan’s environments. Lying in bed, he simply looked onto the wall opposite his bed and could see his hometown illustrated in one of his own paintings. He painted himself as a child in the middle of this painting, as if to remind the fabricated personae of St. E.O.M. of his roots, where he came from, and what created Pasaquan.

Understanding Pasaquan from this perspective pulls us into the darker niches of its creator’s narrative. Everything here is not full of sunlight and beauty. There are real corners of silence just off to the side of blinding rays of brilliance. Pasaquan is several things at the same time. It makes perfect sense that the historic site takes on an emotional fluidity that speaks to a life fully lived. From giving blowjobs to men in dark alleyways of New York City to telling fortunes as the center of Pasaquan, St. E.O.M. was many things.

As a queer person I understand this code switching and the need to be whatever those around need us to be. For many of us, we will always be that little boy in the middle of the painting, walking through Main Street worried about who and what will happen next. For people like St. E.O.M. and me, we never really see a place for ourselves in this world – we must create it ourselves. Out of the discarded and thrown away debris of others, we can make a marvelously special world of color, materials, and theatrics. Not all of you will understand this, but the concept of “drag” is a medicine that saves lives. It builds a defense around that little boy so that he can walk through a life of pain and suffering and still stand in power, substance, and control.

Visiting Pasaquan gave me a moment of understanding–of myself, my jewelry, bracelets, and silk scarves. All of us, in our own way, must find our own Pasaquan in a sea of browns and grey.

Special Thank You Goes To:

Dale Couch – Review

Ruthie Dibble – Review

Charles Flowler – Caretaker at Pasaquan

Fred & Cathy Fussel – Review

Kevin Greenland – Architectural Drawing

June Lucas – Editor

Annie Moye – Chair of Pasaquan Board of Trustees

Tom Patterson – Author

Jon Prown – Review

John Yeagley – Research & Logistics